Shapovalov V. V.,

postgraduate student

Simon Kuznets Kharkiv National University of Economics

Analysis of the global labour market

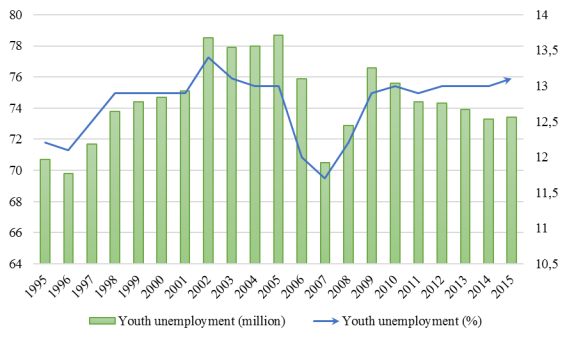

After the period of rapid increase between 2007 and 2010, the

global youth unemployment rate settled at

13.0 per cent for the period from 2012

to 2014. At the same time, the

number of unemployed youth declined by 3.3 million from the crisis peak: 76.6 million youth were unemployed in

2009 compared to an estimated 73.3 million in 2014.

The youth share in total unemployment is also slowly decreasing.

As of 2014, 36.7 per cent of the global

unemployed were youth. Ten years previously, in 2004, the youth share in total unemployment was 41.5 per cent. While the

indicator marks an improvement

over time, it is still worthy of note that youth made up only one-sixth of the global population in 2014 and

are therefore strongly overrepresented among

the unemployed [1].

Despite some signs of “good news” presented above, the instability

of the situation continues and the global

youth unemployment rate today remains well above its precrisis rate of 11.7 per cent in 2007.

Overall, two in five – 42.6 per cent,

economically active youth are still either

unemployed or working yet living in poverty. In the face of such statistics, it is safe to report

it is still not easy to be

young in today’s labour market.

In the Asian regions and in the Middle East and North Africa,

youth unemployment rates worsened

between 2012 and 2014. For the developed economies, the youth unemployment rate improved over the same period, but

still in 2014, rates exceeded 20

per cent in two-thirds of the European countries and more than one in three unemployed youth had been

looking for work for longer than one year.

In Central and South-Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, youth unemployment rates have

demonstrated a declining trend in both the

medium and short-run periods. In all regions the stability of career prospects becomes

increasingly tentative, but the situation could appear more degenerative in the developed

countries where formal employment on a permanent contract was once the standard. In the developed economies, shares

of youth involuntarily working

part-time or engaged in temporary work have declined from the crisis peak, but within a longer term increasing

trend as more young people take up part-time or

temporary work in combination with education [4].

While

the outlook for youth entering the labour market now does look slightly more

positive than for those entering over the previous five years, we should not discount

the lingering harm accruing to the cohorts who experienced long-term unemployment

spells or were forced to take up less-than-ideal jobs during times of low labour

demand. In still too many countries, the youth population continue to suffer

the effects of the economic crisis and austerity

measures put in place as a reaction. In these countries,

finding work, let alone full-time work, as a youth with no work experience

continues to be a drawn-out uphill struggle.

Youth

in developing countries continue to be plagued by working poverty stemming

from the irregularity of work and lack of formal employment and social protection.

In 2014, more than one-third – 37.8 per cent, of

employed youth in the developing world were

living on less than US$2 per day. Working poverty, therefore, affects

as many as 169 million youth in the world. The number increases to 286 million if

the near poor are included (living below US$4 per day) [2].

In

most low-income countries, at least three in four young workers fall within the category

of irregular employment, engaged either in own-account work, contributing family

work, casual paid employment or temporary non-casual labour. Nine in ten young

workers remain in informal employment. This compares to an only slightly improved

share of two in three youth in the middle-income countries.

The

deficiencies in the quality of available employment in most developing countries

block the successful transition of young people but also serve as a severe impediment

to economic development. While development should bring gains in the shares

of youth in paid employment that is neither casual nor temporary in nature, the fact

that we are not there yet has consequences for measurements of youth

transitions.

Results

demonstrate that the transition paths of the most disadvantaged youth

are often the most direct; that is, they move directly from school – if they

even go to school – into the irregular and informal work

that they are likely to continue doing for a lifetime.

Even in developed economies, a short transition period to a first job should

not be overly praised if the job does not offer a good foundation for the

broader transition to a stable and satisfactory job in

adulthood.

The

global youth labour force and labour

force participation rate continues to decline as

enrolment in education increases. Between 1991 and 2014, the share

of active youth (either employed or unemployed) in the youth population declined

by 11.6 percentage points compared to a 1 percentage point

decline in the adult labour force participation rate [7].

The

global youth employment-to-population

ratio – the share of the working-age population

that is employed – declined by 2.7 percentage points

between

2007 and 2014. The declining trends in youth EPRs are

closely linked to increasing trends in educational enrolment.

After

a period of rapid increase between 2007 and 2010, the global youth unemployment rate settled at 13.0

per cent for the period 2012 to 2014 and is expected to increase only slightly to 13.1 per

cent in 2015. The rate has not yet recovered

its pre-crisis rate of 11.7 per cent in 2007.

The

number of unemployed youth has

declined from 76.6 million at the peak of the crisis in

2009 to an estimated 73.3 million in 2014.

Globally,

the ratio of youth to adult

unemployment rates has hardly changed

over

time and stood at 2.9 in 2014. The youth unemployment rate has been consistently

close to three times that of the adult unemployment rate since 1995 [7].

Strategies

to promote youth employment should articulate the mix and

interaction

of macroeconomic policies, labour and employment policies and other

interventions specifically targeting young people, particularly the most disadvantaged. Policies that offer fiscal incentives, support

the development of infrastructure and develop enabling

regulations for enterprises operating in sectors with high

employment

potential can help improve youth employment outcomes.

The

positive effect of public investment on youth employment can be maximized by

ensuring that young workers have the right skills and are supported in the job matching.

In this sense, linking investment in infrastructure with labour market policies

would boost both quantity and quality of jobs for youth.

Comprehensive

packages of active labour market policies that target

disadvantaged

youth can help in the school-to-work transition.

An

increase in public investment, social benefits and active labour market policies

has an impact on youth employment, particularly in terms of labour

market participation. Evidence shows that public spending on labour market

policies is associated with significantly higher youth employment-topopulation ratios

[8].

Specific

policies and targeted interventions to support the transition of young workers

to the formal economy yield better results if designed as part of macroeconomic

policies and include interventions to improve legal and

administrative

requirements for entrepreneurial activity, reforms to advance the quality

of youth employment through access to rights at work, better working conditions

and social protection.

Coordinated

responses and partnerships are required to scale up policies and strategies

that have had an impact on the quantity and quality of jobs for young people.

After

a period of rapid increase between 2007 and 2010, the global youth unemployment

rate settled at 13.0 per cent for the period 2012−14 and is expected to increase

only slightly to 13.1 per cent in 2015. While

this

rate is now on par with rates of the early 2000s, the number of unemployed

youth has shown a significant decline over the same

period: 78.7 million youth were unemployed in 2005, 76.6

million at the peak of the crisis in 2009 and then descending to

an estimated 73.4 million in 2015. That the youth unemployment rate has not decreased

with declining numbers of unemployed youth is a signal of the longer-term trends

in the declining youth labour force, the denominator of the rate. In the

ten-year span between 2005 and 2015, the youth labour

force declined by as much as 46 million while the number

of unemployed youth dropped by 5.3 million [6].

Figure

1 reflects well the cyclical nature of youth

unemployment and reminds us of the often repeated

tenet that youth are among the most severely impacted by

economic

crises; youth are the “first out” as economies contract and the “last in”

during periods of recovery. Evidence from previous

crises suggest that it takes an average of

four

to five years from the resumption of economic growth before overall employment returns

to its pre-crisis levels. Recovery of youth employment can take even longer.

In fact, at this point in time, nearly ten years after the onset of the global economic

crisis, the global youth unemployment rate remains well above the pre-crisis rate

of 11.7 per cent in 2007 [7].

Policies

that promote employment-centred and inclusive growth are vital if young people are to be given a fair chance at a

decent job. Youth labour market outcomes

are closely related to overall employment trends but are also more sensitive to the business cycle as demonstrated in earlier

chapters of this report. A boost in aggregate

demand is key to addressing the youth employment crisis as this will create more job opportunities for young people.

Keeping

youth employment strategies anchored to macroeconomic and sectoral policies

is therefore critical. Far too often, however, interventions that aim to

increase labour demand remain underutilized. It is quite

uncommon to find a comprehensive set of policy priorities,

targets and outcomes for youth employment, let alone with

sufficient

funds and resource allocations.

Macroeconomic

and growth policies can support youth employment if

investments

are sufficient and well placed. Job growth can be spurred by encouraging

economic diversification and structural

transformation. Rural

non-farm economic activities are currently the source of 40 to 70

per cent of rural households’ income in Africa, Asia and

Latin America. A recent analysis of the results of the SWTS concluded that

many countries – especially the low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa – need to

move beyond low-productive agriculture and petty trades in rural areas [3].

In

these countries the promise of rural diversification and structural transformation

has not yet resulted in better jobs for significant shares of young people living

in rural areas.

Strategies

to promote agricultural diversification and expand the productive segments

of the industrial and services sector are required to harness gains from structural

changes and boost labour demand for youth in developing countries. There are

multiple and diverse pathways to structural transformation as highlighted [5].

Regardless

of the policy choice, the State must play an active role, be it

in building markets, nurturing enterprises, encouraging technological

upgrading, supporting learning processes and the

accumulation of capabilities, removing infrastructural

bottlenecks to growth, modernizing agriculture and providing access to finance. Positive

employment outcomes can be encouraged by reducing

macroeconomic volatility

by engaging in timely and targeted counter-cyclical policies. Through fiscal

and monetary policy, central banks and financial

authorities can encourage high levels of investment,

enhance financial inclusion and ensure access to credit, particularly by granting

credits to priority sectors with high potential to create quality employment [4].

The

impact of expansionary fiscal policy on employment

outcomes

has been the subject of research and analysis over the last decade, and, more particularly,

during the economic and financial crisis. In the realm of youth employment, a

argues that counter-cyclical fiscal policy can help

to curb youth unemployment. This instrument is more effective if preceded

by a relatively conservative fiscal policy in non-recessionary periods, by increasing

expenditure and reducing taxes during recessions and doing the opposite during

economic expansion.

References:

1. Behrendt, C. 2013. “Investing in people:

Extending social security through national Social

Protection

Floors”, in I. Islam and D. Kucera (eds): Beyond macroeconomic stability:

Structural transformation and inclusive development

(Geneva,

ILO/Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

2. Divald, S. 2015. Comparative analysis of policies for youth employment in Asia and the

Pacific (Geneva, ILO).

3. Elder, S. 2014. Labour market transitions of young women and men in Asia and the

Pacific, Work4Youth Publication

Series No. 19 (Geneva, ILO).

4. Islam, I.; Kucera, D. 2013. Beyond macroeconomic stability: Structural

transformation and

inclusive development (Geneva,

ILO/Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

5. Islam, R.; Islam, I. 2015. Employment and inclusive development (London,

Routledge Studies in Development Economics).

6. Lieuw-Kie-Song, M.; Puerto, S.; Tsukamoto, M.

(forthcoming). Improving labour market

outcomes of

youth: A review of evidence from public works programmes (Geneva, ILO).

7. Report: Global employment trends for youth 2015: scaling

up investments in decent jobs for youth / International

Labour Office. - Geneva: ILO, 2015

8. Scarpetta,

S.; Sonnet, A. 2012. “Challenges facing European labour markets: Is a skill

upgrade the appropriate

instrument?”, in Intereconomics, Vol. 47, No. 1.