Філологічні науки / Етно-, соціо- та психолінгвістика

К.ф.н. Гоца Н.М.

Тернопільський національний педагогічний

університет імені

Володимира Гнатюка

AFRICAN

AMERICAN LANGUAGE VS

AFRICAN

AMERICAN WOMEN’S LANGUAGE: THEORETICAL PREMISES

To

date, linguistic research has focused primarily on men (European and African

American) and European American women. Because of the dearth in research on the

language of African American women, this thesis focuses on African

American women’s language (AAWL) and traces in what way it differs from African

American Language (AAL) in general.

Very

often AAWL is by mistake identified with African American language (AAL) that

can also be called African American Vernacular Language (AAVL), African

American English (AAE), African American (Afro-American) Black English, Black

English Vernacular (BEV), Ebonics, and other. AAL is an object of discussion of many linguists. They debate

about its status in a language system. Some scientists name it as a language,

others – as a dialect. Great influence on AAL reception was made by scientific

literature that studies this branch of linguistics. With the help of these

works the attitude and politics concerning AAE changed. But the drawback of all

these scientific works is that they pay attention not to basic linguistic

phenomena of the Black language, but to the main aspects of linguistic ethnics.

In the frameworks of our investigation we consider AAL as a component of AAWL,

its constituent part and expressive means of its sociocultural aspect.

It

should be mentioned that AAWL can’t be investigated separately from AAL and

women’s language in general, as it undoubtedly combines linguistic features of

both these notions. But, we also admit that AAWL can be called a separate

linguistic phenomenon, as it represents African American feminism that in its

turn reflects combination of gender and sociocultural aspects of African

American women’s life. The other problem that makes this theme urgent is that

at present, AAWL is still largely misunderstood and mispresented not only in

Black male society, but also in White mainstream society.

So, the

aim of our study is to determine some peculiar characteristics of AAL and AAWL

and to show that AAWL can function as a separate linguistic notion.

We

should say that not so many scientists try to investigate thias urgent but

rather contradictory subject of AAWL. The most well-known are Denise Troutman [9],

Sonja L. Lanehart [7], Marcyliena Morgan [8].

Much more investigations are dedicated to social, historical, psychological, methodological

and less to linguistic peculiarities of AAE. To such researchers belongs J. A

Fishman [4], R. Burling [2], R. Fasold [3], J. Haskins [5], R. H.

Bentley [1], C. Kramasch [6], J. F. Trimmer

[9], and others.

Marcyliena Morgan asserts that first steps in studying AAWL can be

traced in famous “Language and Woman’s Place”

written by Robin Lakoff. Although Lakoff’s focus was on her own language and

that of her peers, this work is a matter of particular importance for African

American women’s discourse as it displays how the field of linguistics can be

changed through the raising of urgently needed questions that are both

particular and universal. In this way it determines a structure from which to

move African American women to the very core of language and gender studies [8,

p. 253].

Denise

Troutman also made great contribution to this theme. She has found some

peculiarities of AAWL similar to European American women’s language. This

scholar distinguished the main problems AAWL faces with. The first problem is

connected with “Black men’s speech”, the second – with “White women’s speech”. She

admits that given the dominant paradigm in research in women’s language in

which White women are privileged and Black women are silenced, one might assume

there is a place for African American women in research on AAE. She says that

however, there is a little research in AAE that corrects or redresses the

absence of the discourse of African American women since research in AAE

privileges African American men. As a result, Black speech style is not viewed

as available to or indicative of African American women. A perception of

African American speech are synonymous with African American men (just as it is

seen as synonymous with White women’s language in the literature on women’s

language) and leaves little or no room for actual voices of African American

women [10, p. 212].

Even

nowadays AAWL is contrasted with AAE and White women’s speech as the following linguistic

stereotypes exist: 1) Black speech – male speech; 2) Black speech – verbally

aggressive; 3) Black speech – implicitly, sexually aggressive speech; 4) Black

speech allows Black women to speak only like men, in verbally and sexually

aggressive way; 5) Black women have only one linguistic choice (to avoid being verbally

and sexually aggressive); 6) Women’s speech is White women’s speech, therefore,

Black women’s speech is White women’s speech [10, p. 212-213].

Scientist

Sonja L. Lanehart also pays great attention to AAWL. But within the frameworks

of her investigations one can notice differences within AAWL itself. Making

comparisons among use of language, S. L. Lanehart demonstrates how differences

in age, education and social status lead to various abilities in using AAWL

language.

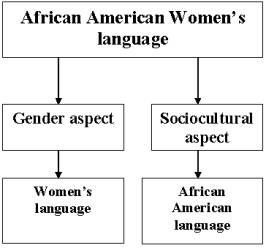

Interconnections

between notions discussed in the investigation can be organised in the

scheme:

So,

AAWL is two-dimensional phenomenon. It combines two main linguistic tendencies

– sociocultural and gender. Women’s language and African American language are

that very aspects that form such linguistic product as African American Women’s

language in particular.

Література

1.

Bentley R.

H. Black Language Reader / R. H. Bentley, S. D. Crawford. – Scott, Foresman and

Company, 1973. – 245 p.

2.

Burling R.

English in Black and White / R. Burling. – HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON, INC,

1973. – 178 p.

3.

Fasold R.

Some Linguistic Features of Negro Dialect / Ralph Fasold // Black American

English : its Background and its usage in the schools and in

literature / edited and introduced by

Paul Stoller. – A Delta Original, 1975. – P. 49–83.

4.

Fishman J.

A. Language and Ethnic Identity / Joshua A. Fishman. – Oxford : Oxford

University Press, 1999. – 468 p.

5.

Haskins J.

The Psychology of Black Language / H. Butts, J. Haskins. – Barnes & Noble

Books, 1973. – 95 p.

6.

Kramasch C.

Language and Culture / Claire Kramasch. – Oxford : Oxford University Press,

2000. – 134 p.

7.

Lanehart Sonja L. Sista, Speak!:

Black Women Kinfolk Talk about Language and Literacy / Sonja L. Lanehart.

– University of

Texas Press, 2002. – 252 p.

8.

Morgan M. “I’m Every Woman”: Black

Women’s (Dis)placement in Women’s language study / Marcyliena Morgan // Language

and Woman’s Place: Text and Commentaries / ed. by Mary Bucholtz. – Oxford University Press, 2004. – 320 p.

9.

Trimmer J.

F. Black-American Literature: Notes on the Problem of Definition / J. F.

Trimmer. – Ball State

Monograph Number Twenty-Two, 1971. – 28 p.

10.

Troutman, Denise. African American women: Talking that

talk / Denise Troutman // Sociocultural and Historical Contexts of African

American English / ed. by Sonja L. Lanehart. – John Benjamins Publishing,

2001. – 371p.