National Technical University of Ukraine

«Kiev Polytechnic

Institute»

“Kamikaze” – an extreme form

of penetration pricing

An extreme form of penetration

pricing is "kamikaze" pricing, a reference to the Japanese dive

bomber pilots of World War II who were willing to sacrifice their lives by

crashing their explosives-laden airplanes onto enemy ships. In the business

world, the relentless pursuit of more sales through lower prices usually

results in lower profitability. It is often an unnecessary and fruitless

exercise that damages the entire dive-bombing company—not just one

individual—along with the competitor. Judicious use of the tactic is advised;

in as many cases as it works, there are many more where it does not.

Kamikaze pricing occurs when the

justification for penetration pricing is flawed, as when marketers incorrectly

assume lower prices will increase sales. This may he true in growth markets

where lower prices can expand the total market, but in mature markets a low

price merely causes the same customers to switch suppliers. In the global

economy, market after market is being discovered, developed, and penetrated.

High growth, price sensitive markets are quickly maturing, and even though

customers may want to buy a low- priced product, they don't increase their

volume of purchases. Price cuts used to get them to switch fail to bring large

increases in demand and end up shrinking the dollar size of the market.

A prominent example is the

semiconductor business, where earlier price competition led to both higher

demand and reduced costs. But in recent years, total demand tends to be less

responsive to lower prices, and most suppliers are well down the experience

curve. The net result is an industry where participation requires huge investments,

added value is immense, but because of a penetration price mentality, suppliers

can't pull out of the kamikaze death spiral.

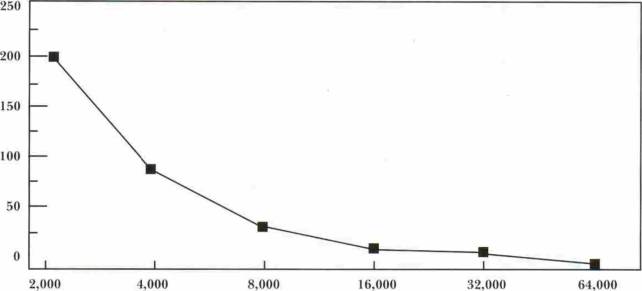

Another risk comes in using

penetration pricing to increase sales in order to drive down unit costs.

Unfortunately, there are generally two reasons managers run into trouble when

they justify price discounts by anticipated reductions in costs. First, they

view the relationship between costs and volume as linear, when it actually is

exponential—the cost reduction per unit becomes smaller with larger increases

in volume. Initial savings are substantial, but as sales grow, the incremental

savings per unit of production all but disappear (Picture 1). Costs continue to

decline on a per unit basis, but the incremental cost reduction seen from each

additional unit of sale becomes insignificant. Managers need to recognize that

experience curve cost savings as a percentage of incremental sales volume

declines with increases in volume. It works great in early growth phases but

not in the later stages.

Picture 1

Disappearing savings

Dollar

savings per 1.000 additional units

Current

volume of production

Many managers believe that sales

volume is king. They evaluate the success of both their sales managers and

marketing managers by their ability lo grow sales volume. The problem is that

their competitors employ the exact same strategy. Customers learn that they

can switch loyalties with little risk and start buying lower priced

alternatives. Marketers find themselves stuck with a deadly mix of negligible

cost benefits, inelastic demand, aggressive competition, and no sustainable competitive

advantage. Any attempt to reduce price in this environment will often trigger

growing losses. To make matters worse, customers who buy based on price are

often more expensive lo serve and yield lower total profits than do loyal

customers. Thus starts the death spiral of the kamikaze pricers who find their

costs going up and their profits disappearing.

Penetration pricing is overused,

in large part, because managers think in terms of sports instead of military

analogies. In sports, the act of playing is enough to justify the effort. The

objective might be to win a particular game, but the implications of losing are

minimal. The more intense the process, the better the game, and the best way to

play is to play as hard as you can.

This is exactly the wrong

motivation for pricing where the ultimate objective is profit. The more intense

the competition, the worse it is for all who play. Aggressive price competition

means that few survive the process and even fewer make reasonable returns on

their investments. In pricing, the long-term implications of each battle must

be considered in order to make thoughtful decisions about which battles to

fight. Unfortunately, many managers find that, in winning too many pricing

battles, they often lose the war for profitability.