V. Sigitov, D.Batyrbekuly

Kazakh-British Technical University

ESTIMATION

OF POSTTREATMENT SKIN FACTOR VALUE

AT

KUMKOL OILFIELD

In

the article below, it was explained the primary goal of well stimulation, which

is to increase the productivity of a well by removing damage in the vicinity of

the wellbore or by superimposing a highly conductive structure on to the

formation. New and novel fracture stimulation technologies can provide

attractive deliverability enhancement results. Even though fracture stimulation

was very successful at several test sites and led to significant improvements

in deliverability, not every stimulation treatment was effective. The most

consistently effective stimulation technology should be hydraulic fracturing.

In

the paper, we tried to pay your attention to Hydraulic fracturing, the

stimulation method which is intended

to provide a net increase in the productivity index, that can be used either to

increase the production rate or to decrease the drawdown pressure differential.

A decrease in drawdown can help prevent sand production and water coning, and

shift the phase equilibrium in the near well zone toward smaller fractions of

condensate. Injection wells also benefit from stimulation in a similar manner.

Commonly used stimulation techniques except hydraulic fracturing, include

fracpack, carbonate and sandstone matrix stimulation (primarily acidizing), and

fracture acidizing.

Many

reservoirs must be hydraulically fractured to become economically productive.

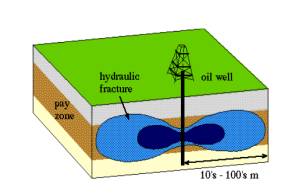

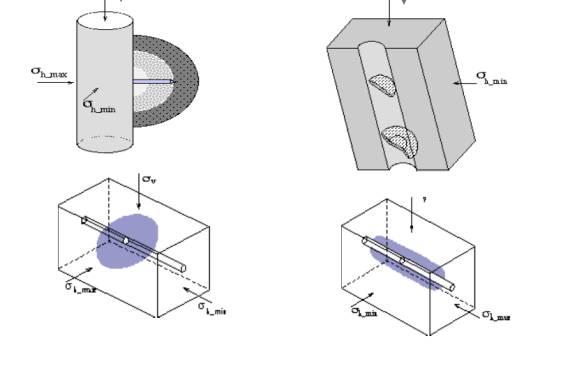

Hydraulic

fracturing involves injecting a large volume of proppant-laden fluid at a

pressure sufficiently high to fracture the formation. After the fracturing

fluid leaks off into the formation, the remaining proppant keeps the fracture

open. Although a hydraulic fracture is narrow (a fraction of an inch in most

cases), the presence of this high-permeability channel significantly enhances

the productivity of the well. The presence of a fracture alters the flow regime

inside the formation as the fluid flows into the fracture and then through the

fracture into the wellbore, with very little or no fluid flowing directly from

the formation into the wellbore. The presence of a hydraulic fracture adds

another dimension to the fluid flow in porous media and to well test design and

analysis.

Using

of hydraulic fracturing at KUMKOL oilfield recommends starting at J-II horizon,

with installation of packer against clay in the interval: 1300.0-1305.0 m.

Necessary

measures before doing hydraulic fracturing are:

- Isolation of interval 1312.0-1316.0 m, at

the bottom, where it was fluid flow

with

water (December, 2001)

- Installation of cement plug at the depth of

1317.0 m in order to avoid

deformation

of casing against water producing formation of J-III horizon.

- Re-perforation filter 1305.6-1308.4m

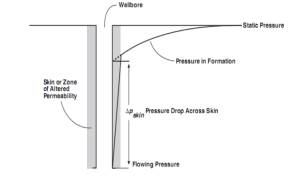

Figure – 1.Pressure

distribution in a reservoir with a skin

It

was proven that as a result of drilling and completion practices, the formation

permeability

near the wellbore are usually reduced. Drilling fluid invasion of the

formation, dispersion of clay, presence of a mudcake and cement tend to reduce

the formation permeability around the wellbore. A similar effect can be

produced by a decrease in the area of flow exposed to the wellbore. Therefore,

partial well penetration, limited perforation, or plugging of perforations

would also give the impression of a damaged formation. Conversely, an inclined

well or inclined formation increases the area of flow near the wellbore, giving

the impression of a stimulated well. The zone of reduced (or higher) formation

permeability has been called a ‘‘skin,’’ and the resulting effect on well

performance is called ‘‘skin factor.’’ Skin factor can be used as a relative

index to determine the efficiency of drilling and completion practices. It is

positive for a damaged well, negative for a stimulated well, and zero for an

unchanged well (Figure-1). Acidized wells usually show a negative skin.

Hydraulically fractured wells show negative values of skin factor that maybe as

low as -7. Well stimulation ranks second only to reservoir description and

evaluation as a topic of research or publication within the well construction

process. There as, on for this intense focus is simple: this operation

increases the production of petroleum from the reservoir. Thus, this facet of

the construction process actively and positively affects a reservoir’s

productivity, where as most of the other operations in this process are aimed

at minimizing reservoir damage or eliminating production problems.

Hydraulic

fracturing is a proven technological advancement which allows natural gas

producers

to safely recover natural gas from deep shale formations. This has the

potential to not only dramatically reduce our reliance on foreign fuel imports,

but also to significantly reduce our national carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions

and to accelerate our transition to a carbon-light environment. Experts have

known for years that natural gas deposits existed in deep shale formations, but

until recently the vast quantities of natural gas in these formations were not

thought to be recoverable. Today, through the use of hydraulic fracturing,

combined with sophisticated horizontal drilling, extraordinary amounts of

natural gas from deep shale formations across the United States are being

safely produced. Hydraulic fracturing has been used by the oil and gas industry

since the 1940s and has become a key element of natural gas development

worldwide. In fact, this process is used in nearly all natural gas wells

drilled in the U.S. today. That’s why we should use this method almost in all

oil and gas wells in Kazakhstan. Properly conducted modern hydraulic fracturing

is a safe, sophisticated, highly engineered and controlled procedure.

KEY

POINTS:

•

Hydraulic fracturing is essential for the production of natural gas from shale

formations.

•

Fracturing fluids are comprised of more than 99% water and sand and are handled

in

self

contained systems.

•

Freshwater aquifers are protected by multiple layers of protective steel casing

surrounded

by cement; this is administered and enforced under state regulations.

•

Deep shale gas formations exist many thousands of feet underground.

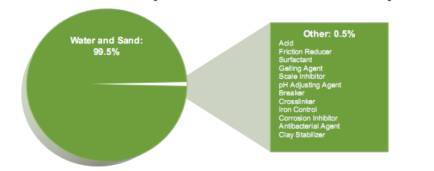

Fracturing Fluid

Makeup

In

addition to water and sand, other additives are used in fracturing fluids to

allow

fracturing

to be performed in a safe and effective manner. Additives used in hydraulic

fracturing

fluids include a number of compounds found in common consumer products.

Hydraulic

fracturing consists of injecting fluid into the formation with such pressure

that it induces the parting of the formation. Proppants are used in hydraulic

fracturing to prop or hold open the created fracture after the hydraulic

pressure used to generate the fracture has been relieved. The fracture filled

with proppant creates a narrow but very conductive path towards the wellbore.

In almost all cases, the overwhelming part of the production comes into the

wellbore through the fracture; therefore, the originally present near-wellbore

damage is ‘‘bypassed,’’ and the pretreatment positive skin does not affect the

performance of the fractured well. Perhaps the best single variable to

characterize the size of a fracturing treatment is the amount of proppant

placed into the formation. Obviously, more propped fracture volume increases

the performance better than less, if placed in the right location. In

accordance with the general sizing approach outlined above, the final decision

on the size of the fracturing treatment should be made based on the NPV analysis.

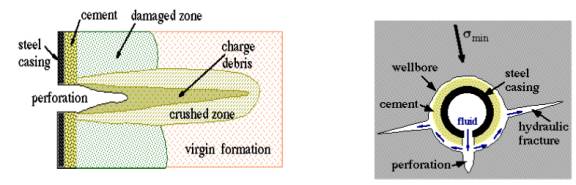

Often

the well is cased a steel casing cemented to the rock. The pressurized fluid

that causes cracking must be allowed to pass from the cased well bore to the

rock. This is done by perforating the casing and cement. The process of

perforating the casing causes damage to the rock as well as the cement bond

between the steel and the rock. Fluid may be able to enter the interface

between these materials and fracture initiation may not occur from the

perforations as desired.

Finally,

the wells may not always be vertical and the fractures may not always be simple

planar features. Multiple deviated wells are commonly drilled from ocean

drilling platforms,and horizontal wells are increasing. Fractures from these

various wells, in addition to vertical wells, need to be modeled.

Example of Typical

Deep Shale Fracturing Mixture Makeup

A

representation showing the percent by volume composition of typical deep shale

gas hydraulic fracture components (see graphic) reveals that more than 99% of

the fracturing mixture is comprised of freshwater and sand. This mixture is

injected into deep shale gas formations and is typically confined by many

thousands of feet of rock layers.

To

sum it up, engineers design a fracturing operation based on the unique

characteristics of the formation and reservoir. Basic components of the

fracturing design include the injection pressure, and the types and volumes of

materials (e.g., chemicals, fluids, gases, and proppants) needed to achieve the

desired stimulation of the formation.

When

applied to stimulation of water injection wells, or oil/gas wells, the

objective of hydraulic fracturing is to increase the amount of exposure a well

has to the surrounding

formation

and to provide a conductive channel through which the fluid can flow easily to

the well. Computer models are used to simulate fracture pathways, but the few

experiments in which fractures have been exposed through coring or mining have

shown that hydraulic fractures can behave much differently than predicted by

models.

References:

1.

Economides,

M.J., and Nolte, K. (eds.), Reservoir Stimulation (2nded.), Prentice Hall,

2.

Englewood

Cliffs, NJ (1989).

3.

Haimson,

B.C., and Fairhurst, C.:‘‘Initiation and Extension of Hydraulic Fractures in

4.

Rocks,’’ SPEJ

(Sept.1967)310–318.

5.

"Application

of New and Novel Fracture Stimulation Technologies to Enhance the

6.

Deliverability

of Gas Storage Wells," Topical Report, Contract No. DE-AC21-94MC31112,

U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, DC (April, 1995).

7.

4. Gidley,

J.L., Holditch, S.A., Nierode, D.E., and Veatch, R.W., Jr. (eds.), Recent

8.

Advances in

Hydraulic Fracturing, Richardson, TX (1989), SPEMonograph12.