Ph.D. in Biology, Murylev A. V.

Perm State Humanitarian

Pedagogical University, Russia

SUPERCOOLING

POINTS OF APIS MELLIFERA MELLIFERA

AND APIS MELLIFERA CARPATHICA

INTRODUCTION

Perm krai marks

the northern limit of the natural distribution range of honeybees. Honeybees of

the Apis mellifera mellifera L.

successfully overwinter in this area and display high degrees of productivity.

In the Perm krai Region, the Kama Region population of A. m. mellifera has been recognized [7], distinguished by

morphological and ecophysiological characters from other A. m. mellifera populations

of Russia. Honeybees of this population have a genetically secured complex of

adaptations to northern environmental conditions. In addition to the Perm krai

Region population of A. m. mellifera,

some beekeepers have started breeding at their apiaries the more peaceful Apis mellifera carpathica. The A. m. carpathica have been brought to

the Perm krai Region for this experiment from the Mukachevo Purebreed Bee

Nursery, Ukraine. It is known that not all organisms are able to successfully

adapt to new ecological and geographical conditions, however, some positive

qualities encourage beekeepers to acclimatize separate races of bees outside

the borders of their natural habitats. The adaptations of these bees evolved

under the conditions of their southern range and are distinguished by some

peculiar features. They have a body size smaller than that of the A. m. mellifera, but their proboscis

length is slightly longer, allowing them to use a wider range of meliferous

plants [2]. Ecological and biological characteristics of bees Carpathian race

for them in unusual climatic conditions remain poorly studied.

The cold-hardiness

of insects is usually estimated by the supercooling point (SCP), a parameter of

proposed by Bakhmet'ev [1]. Crystallization is usually lethal to the insect,

because it damages the tissues of its body. In the light of new technical

abilities and the emergence of new technologies, the study of the SCP parameter

continues also at the current stage of scientific development [4; 5]. It is

especially important for characterizing different honeybee subspecies [6].

The purposes of

this study were to analyze the resistance to low temperatures in honeybees of

the Kama Region population of the A. m.

mellifera and those of the A. m.

carpathica on individuals of the spring, summer, and autumn generations and

the total percentage of water in the body of honeybees during different periods

of bee family development.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

The experiments

were performed monthly from 2010 to 2013. The materials included bees of the

Kama Region population of the A. m.

mellifera from the Nizhnesypovskoe Bee Breeding Farm (Uinskoe district,

Perm krai) and bees of the A. m.

carpathica brought to Perm krai from the Mukachevo Purebreed Bee Nursery,

Ukraine.

Instruments and testing methods for the testing of SCP

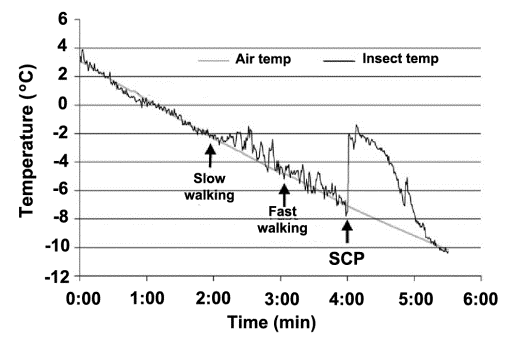

SCP was measured

according to the method proposed by Es'kov [3], in each of the three tagmata

(head, thorax, and abdomen). A total of 20 bees of the studied races were used

every month. The measurements were taken using a chrome/copel thermocouple

fixed on a wooden base. The thermocouple was attached to one of the body parts

of bees vaseline, and then placed in the freezer compartment of the refrigerator.

The temperature values of SCP were recorded with a Termodat-38M2 device. SCP is

determined by measuring the heat released in the course of crystallization,

when matter transforms from the liquid to the solid state (fig. 1). Simultaneously,

SCP was compared to the total water content in the body of honeybees of

different generations.

Testing of water content

The total amount

of water in the body was determined as the difference between two results of

weighing the bee's body: wet weight and constant weight after drying the

specimen at 102°C for 48 hours.

Fig. 1. Supercooling

point of insects

RESULTS

Research results

showed that the total water content in the body of honeybees changes over the

year. With the cessation of flying activity in September or October and gradual

advent of the cold period, the water content in the body of bees of the autumn

generation decreases by 8 %, leading to a slowdown of metabolic processes. Bee

families enter a period of physiological dormancy of development and reproduction.

During this period, a decrease in the supercooling point has been recorded

(table).

In February, bees

display the lowest water content in the body; by this time, the supercooling

point also reaches its lowest subzero values. Significant differences in these

parameters have been found between the studied races in bees of the autumn

generation (t = 4.08, p<0.01). In

April, overwintered bees are replaced by young bees of the spring generation.

The young bees

display a higher water content in the body and an increase of SCP in the

tagmata. During the period of intense growth and accumulation of inactive bees,

which start working during the period of principal honey flow, the supercooling

point in the tagmata continues growing. Bees of the summer generation emerge,

which display the highest water content in the body and the highest values of

SCP. These parameters remain high until October, and then decrease again. In

bees of the summer generation, differences between the subspecies proved

insignificant (t = 2.48, p>0.05). Positive correlation has been observed

between the values of SCP and the total water content in the body: the

correlation coefficient is 0.84 in the Kama Region bees of the A. m. mellifera and 0.92 in those of the A. m. carpathica.

Dynamics of SCP and water content in the body of bees

of the Apis m.

mellifera and Apis m. carpathica

|

Generation of bees |

Apis

m. mellifera |

Apis

m. carpathica |

||||||

|

Water content, %, n = 180 |

SCP, (Ò±m), °Ñ, n =

180 |

Water content, % |

SCP, (Ò±m), °Ñ, n = 180 |

|||||

|

head |

thorax |

abdomen |

head |

thorax |

abdomen |

|||

|

Spring |

65.67 |

–7.45± 0.08 |

–5.67± 0.10 |

–4.93± 0.02 |

71.29 |

–7.01± 0.12 |

–5.56± 0.12 |

–5.01± 0.04 |

|

Summer |

72.42 |

–4.45± 0.02 |

–4.56± 0.07 |

–3.98± 0.08 |

74.19 |

–4.42± 0.04 |

–4.50± 0.01 |

–4.02± 0.04 |

|

Autumn (October-December) |

64.31 |

–7.83± 0.12 |

–6.68± 0.09 |

–5.81± 0.09 |

69.25 |

–7.12± 0.13 |

–5.81± 0.08 |

–5.54± 0.11 |

|

Autumn (January-March) |

63.22 |

–10.61± 0.06 |

–8.25± 0.05 |

–8.04± 0.07 |

67.34 |

–9.74± 0.09 |

–7.12± 0.12 |

–7.24± 0.10 |

Analysis of SCP

values recorded in different tagmata of honeybeesshows that in the Kama Region

population of the A. m. mellifera the

lowest values of SCP in the head were observed in February, reaching -10.61 ±

0.06°C (n = 180), while in the A. m.

carpathica the lowest values were observed in March, reaching -9.74 ± 0.09°C

(n = 180) (table). The values of SCP in the thorax were higher: in bees of the

Kama Region population of the A. m.

mellifera they reached ‑8.25 ± 0.05°C (n = 180) in February, and in

those of the A. m. carpathica they

reached -7.12 ± 0.12°C (n = 180) in March. In the abdomen, the lowest values of

SCP in the Kama Region population of the A.

m. mellifera were observed in March, reaching -8.04 ± 0.07°C (n = 180); in

bees of the A. m. carpathica they

were also observed in March, reaching -7.24 ± 0.10°C (n = 180). In addition, it

has been noted that at the end of overwintering A. m. carpathica switch to the active state 15 to 20 days earlier

than A. m. mellifera ones. Bees of

the former race start nurturing their brood already in March, according to

their genetic program, although the flying period starts only some 20 days

later. A. m. mellifera start

nurturing their brood only after the start of their flight. In March they continue

to build a winter club.

CONCLUSIONS

The lowest

supercooling point values have been recorded in bees with the lowest water

content in the body. The water content in the body of bees from the Kama Region

population of the A. m. mellifera is

lower during the entire annual cycle than in those of the A. m. carpathica. Summer bees had the highest SCP temperature and

high water content. It has been shown that A.

m. carpathica are less physiologically adapted to long overwintering under

low temperatures. In combination with other factors (such as diseases or the

duration of the flightless period), these parameters can have an adverse effect

on the overwintering of A. m. carpathica

in Perm krai.

REFERENCES

1. Bakhmetyev P.

(1898) – The temperature of insects. Scientific Review., 5: 1602–1611.

2. Bodnarchuk L.

I., Gaidar V. A., Pilipenko V. P. (2008) – Carpathian bee, what are they? Bee J., 2: 1–2.

3. Eskov E. K. (1991)

– Methods and techniques of experimental zoology. Ryazan. ped. Inst. Press, Ryazan.

4. Eskov E. K.

(2007) – The temperature of maximum supercooling and the state of the fat body

of bees. J. Beekeeping., 6: 22–23.

5. Heinrich B.

(1993) – The Hot-blooded Insects, Strategies and Mechanisms of

Thermoregulation, Springer Press, Heidelberg, Berlin.

6. Murylev A. V.,

Petukhov A. V. (2011) – The point of crystallization of different parts of the

body bee populations Kama. J. Beekeeping,

1: 18–19.

7. Shurakov A. I.,

Petukhov A. V., Eskov E. K. (1999) – Saving the gene pool of the Central

Russian bees, and basic directions of development of beekeeping in the Perm

region. Perm. State. ped. University Press, Perm.