Ospangazieva N.B.

Al-Farabi Kazakh

National University and Institute of linguistics named after A.Baitursynuly, Kazakhstan

HISTORY OF PHONOLOGY OF THE TURKIC-SPEAKING PEOPLE

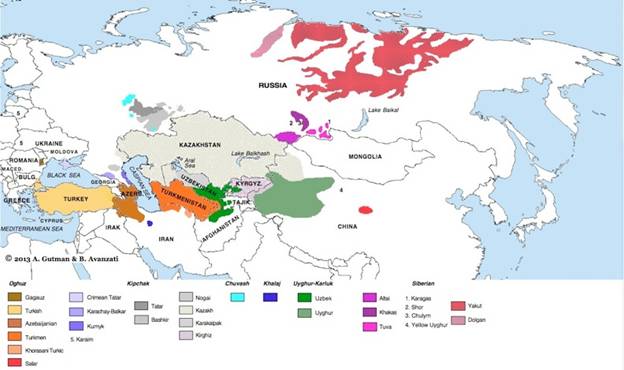

The

Turkic languages are spoken over a large geographical area in Europe and Asia.

How we know, it is spoken in the Azeri, the Türkmen, the Tartar, the

Uzbek, the Baskurti, the Nogay, the Kyrgyz, the Kazakh, the Yakuti, the Cuvas

and other dialects. Turkic languages are distributed over a vast territory

ranging from eastern Europe to east Siberia and China. Their core area is in

Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Xinjiang in

China) from where they spread west to northern Iran and the South Caucasus,

Turkey and part of the Balkans, and to the north into European and Asiatic

Russia straddling the Volga, Ob and Yenisei rivers reaching northeast Siberia

and the Arctic Ocean.

The total number of Turkic speakers is close to 164 million. Linguists

distinguish four main groups among Turkic languages:

North Western (Kipchak), South Western (Oghuz), South Eastern (Karluk)

and North Eastern (Siberian), the latter being a special case. As a matter of

fact,the northwestern, or Kipchak, branch comprises three groups. The South

Kipchak group (NWs) consists of Kazakh (spoken in Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, and so

on), its close relative Karakalpak (mainly Karakalpakstan), Nogay (Circassia,

Dagestan), and Kyrgyz (Kyrgyzstan, China). The North Kipchak group (NWn)

consists of Tatar (Tatarstan, Russia; China; Romania; Bulgaria; and so on),

Bashkir (Bashkortostan, Russia), and West Siberian dialects (Tepter, Tobol,

Irtysh, and so on). The West Kipchak group (NWw) today consists of small,

partly endangered languages, Kumyk (Dagestan), Karachay and Balkar (North

Caucasus), Crimean Tatar, and Karaim. The Karachay and Balkars and Crimean

Tatars were deported during World War II; the latter were allowed to resettle

in Crimea only after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. Karaim is

preserved in Lithuania and Ukraine. The languages of the Pechenegs and the

Kuman are antecedents of modern West Kipchak.

The southeastern, or Uighur-Chagatai, branch comprises two groups. The

western group (SEw) consists of Uzbek (spoken in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan,

Xinjiang, Karakalpakstan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan). An

eastern group (SEe) comprises Uighur and Eastern Turki dialects (Xinjiang,

China; Uzbekistan; Kazakhstan; Kyrgyzstan). Eastern Turki oasis dialects are

spoken in the Chinese cities of Kashgar, Yarkand, Ho-T’ien (Khotan), A-k’o-su

(Aksu), Turfan, and so on; Taranchi in the Ili valley. Yellow Uighur (spoken in

Kansu, China) and Salar (mainly Tsinghai), the latter of Oghuz origin, are small

and deviant languages. Old Uighur and Chagatai are antecedents of the modern SE

branch.

The northeastern, or Siberian, branch comprises two groups. The North

Siberian group (NEn) consists of Sakha and Dolgan (spoken in Sakha republic

[Yakutia]), differing considerably from mainstream Turkic owing to long

geographic isolation. The heterogeneous South Siberian group - comprises three

types. One is represented by Khakas and Shor (both written) and dialects such

as Sagay, Kacha, Koybal, Kyzyl, Küerik, and Chulym (spoken in the Abakan

River area). The second type is represented by Tyvan (Tuvan; spoken in Tyva

[Tuva] republic of Russia and in western Mongolia) and Tofa (northern Sayan

region), both written languages. The third type includes dialects such as Altay

(a written language), Kumanda, Lebed, Tuba, Teleut, Teleng, Tölös,

and others (northern Altai, Baraba Steppe), some being rather similar to

Kyrgyz.

The Turkic languages

are clearly interrelated, showing close similarities in phonology, morphology,

and syntax. According this we can say that they have differences in their

phonology. -Syllable structure. Most syllables have a (C)V(C) structure i.e.

they contain a vowel that may be preceded by an initial consonant and/or

followed by a final consonant. Initial consonant clusters are avoided as well

as vowel hiatus (two adjacent vowels in different syllables). Many Turkic

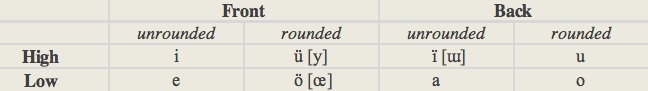

languages (Turkish among them) have a completely symmetrical vowel system

regarding height (4 high and 4 low vowels), frontness (4 front and 4 back), and

roundness (4 unrounded and 4 rounded):

-

·

The symbols are those current in writing, when they

differ from those of the International Phonetic Alphabet the latter are

indicated between brackets. Most

Turkic languages have a contrast between voiceless and voiced stops and

fricatives, though a few others. The most general type is intrasyllabic

affecting the vowel and consonant(s) of a given syllable. The whole syllable is

classified as front or back; in front syllables only front vowels and front

consonants are allowed; in back syllables the opposite is true. There is also

an intersyllabic type of harmony in which words tend to consist of syllables

produced with either a back or a front tongue position. In some languages, like

Kazakh and Kirghiz, harmony may be extended to vowel roundness. I want to show

you one example according the phonology. The word “A bear” in a different

Turkic language:

Azeri: ayı

·

Ancient Türk: ayıg

·

Gagauz: ayı

·

Kazak: àþ (ayu)

·

Crimean Tatar: ayuv

·

Uzbek: ayiq

·

Tatar: ayu

·

Türkmen: aýy

·

Uygur: ئېيىق (ayıq)

As a Kazakh, I can

read Kyrgyz news from internet but I can only understand like 20 percent when

my Kyrgyz friend speaks. The main difference is in pronunciation rather than

grammar and writing as I observe.

Summarize all of this I can say with a little practice, most Turkic languages

could be intelligible.