Voronin I., Kaliberda

N.V.

Oles Honchar Dnipropetrovsk National University

The computer that never crashes

OUT of chaos, comes order. A

computer that mimics the apparent randomness found in nature can instantly

recover from crashes by repairing corrupted data.

For much people it is fantastic, but operating at

University College London (UCL) could keep mission-critical systems working.

For instance, it could allow drones to reprogram themselves to cope with combat

damage, or help create more realistic models of the human brain.

Everyday computers are ill suited to modelling natural

processes such as how neurons work or how bees swarm. This is because they plod

along sequentially, executing one instruction at a time. "Nature isn't

like that," says UCL computer scientist Peter Bentley. "Its processes

are distributed, decentralised and probabilistic. And they are fault tolerant,

able to heal themselves. A computer should be able to do that."

Systemic computation adopts a holistic analysis

approach of systems embracing the significant importance of the interactions of

their fundamental elements and their environment. Its intention is to resemble

natural computation, in order to simulate biological processes effectively, by

following a set of simple conventions :

1. everything is a system,

2. systems may comprise or share other nested systems,

3. systems can be transformed but never destroyed or created from

nothing,

4. interaction between systems may cause transformation of those systems

according to a contextual system,

5. all systems can potentially act as context and interact in some

context,

6. the transformation of systems is constrained by the scope of systems,

and finally

7. computation is transformation.

It doesn't sound like it should work, but it does.

Bentley will tell a conference on evolvable systems in Singapore in April that

it works much faster than expected.

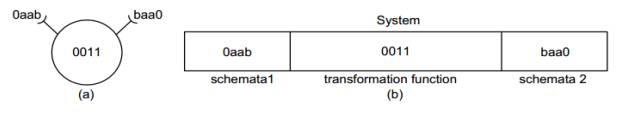

The interaction of two systems can be described by the

systems themselves and a third “contextual” system (which is referred to as

context) which denotes how/if the interacting systems are transformed after

their interaction. The notions of schemata and transformation function are used

in [1] to describe the interaction. Each system comprises of three parts, two

schemata and one transformation function (see Figure 1). The function consists

of an instruction from the SC instruction set (more advanced SC implementations

may allow a transformation function to comprise multiple instructions). Both

systems may change after an interaction, which implies circular causality (each

system may affect the other). The scope here, as in nature, is an important

factor. The scope of a system defines the neighborhood (which can be other than

spatial) in which the system can interact with other systems in a certain way,

denoted by the context. Systems are represented as binary strings.

Fig. 1. SC notation and systems representation: a)

Graphical representation of a system. b) The three elements of a system.

Pairs of systems always interact with a context; these

systems constitute a valid triplet. The schemata of the context provide

templates for the operand systems to match in order to interact, provided that

all three systems belong in the same scope. Thus all computations involve:

• finding valid

triplets (context and two matching systems in a shared scope) and

• updating the two

systems according to the transformation function in the context.

The pair are now working on teaching the computer to

rewrite its own code in response to changes in its environment, through machine

learning.

"It's interesting work," says Steve Furber

at the University of Manchester, UK, who is developing a billion-neuron,

brain-like computer called Spinnaker (see "Build yourself a brain").

Indeed, he could even help out the UCL team. "Spinnaker would be a good

programmable platform for modelling much larger-scale systemic computing

systems," he says.