prof.A.Drobyshev,

A.Aldiyarov,D.Maussymbayev, A.Timchenko, A.Shinbayeva

Al – Farabi Kazakh

National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Research processes of

formation and properties of clusters of methane in water cryomatrix.

1.Abstract

Nowadays natural gas hydrates attract

special attention as a possible source of fossil fuel. According to various

estimates, the reserves of hydrocarbons in hydrates considerably exceed

explored reserves of natural gas. Due to the clathrate structure the unit

volume of the gas hydrate can contain up to 160-180volumes of pure gas. In

recent years interest to a problem of gas hydrates considerably has increased.

It is connected with the progress of searches of alternative sources of

hydrocarbonic raw materials in countries that do not possess the resources of

energy carriers. Thus gas hydrates are nonconventional sources of the

hydrocarbonic raw materials which can be developed next years.

At the same time, there was not full understanding of mechanisms of

formational clathrates of methane hydrates, their thermophysical and mechanical

properties were investigated low[1]. Regarding this experimental modeling of

the processes of formational clathrate hydrates of methane in water cryomatrix

in the process of co-condensation from gas phase on cooled substrate in the range of condensation temperatures

T=(12-60)K and pressures P=(10-4-10-6) Torr.

Concentration of methane in water varied in the range of 1-10%. The thickness

of a film was 30-60 mcm. The vibrational spectra of two-component thin films of

cryovacuum condensates of CH4+H2O were measured and

analyzed.

2.Experiments

and measurement procedure

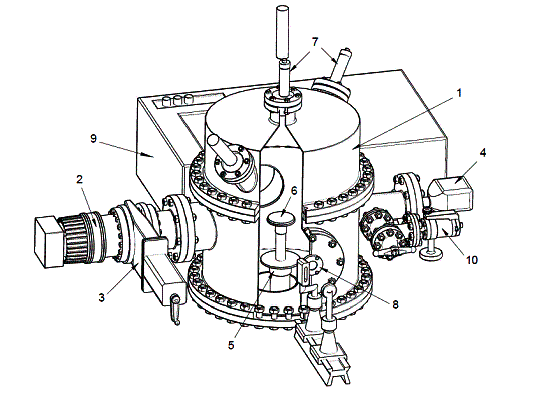

At the core of procedure for obtaining

information about the state of methane molecules in the matrix of different

gases is an analysis of the absorptive amplitude of band, which corresponds to

the vibrations of the methane molecule in the unbounded state. The measurements

were performed at the system, which scheme is given in Fig.1. The main unit of

the system is a cylindrical vacuum chamber (1) in diameter and a height of 450

mm. Pumping out the vacuum chamber was carried out by turbo-molecular pump

Turbo-V-301 (2), which was connected to the chamber through the sliding vane

gate valve CFF-100 (3). As a

backing vacuum pump was used dry spiral pump SH-110 (not shown at the picture).

The ultimate vacuum in the chamber reaches the value not worse than Ð=10-8Torr.

Measuring the pressure in the chamber was carried out with wide-range pressure

transducer FRG-700 (4) with the controller AGC-100.

In the center of the chamber is located

microcryogenic system of Gifford-McMahon (5), on the top flange of which is

mounted mirror substrate (6), serving as condensation surface of mixture of

nitrogen and water. The substrate is made from copper, the working surface of

which is covered with silver. The diameter of the substrate is d=60 mm. The

minimum temperature of condensation is Ò=12Ê. The temperature measurement was

carried out by silicon sensor TS 670-1.4 using a temperature

controllerÌ335/20ñ. Measurement of thickness and rate of condensation is

carried out by a double-beam laser interferometer based on photo-electron-multiplier

P25a-SS-0-100 (7). IR absorption spectra were measured in the frequency range

400 cm-1 – 4200 cm-1.

To obtain a mixture of the test substance

with a matrix gas was used calibrated volume (not shown at the picture). At

first the scope was filled with the investigated gas (methane) up to necessary

pressure. Typically, the pressure value was 1-1,5Òîrr. Thereafter, the

calibration volume was filled with water vapor up to the required pressure,

which corresponds to a working concentration. For the preparation of mixture

was used pressure controller PR 4000 (MKS) with an accuracy of measurement of

pressure 0,01Torr.

Fig.

1- Experimental installation. 1- vacuum chamber; 2- pump Turbo-V-301, 3-

sliding vane gate valve CFF-100; 4-

pressure transducer FRG-700; 5-

microcryogenic system of Gifford-McMahon;

6- substrate; 7-

photomultiplier; 8-optical channel; 9-IR-spectrometr; 10-lake system

There is a following procedure for the

performance of the experiment. The vacuum chamber was pumped out up to a pressure

of Ð=10-8Torr, then to prevent contamination the substrate was

overlapping with the protective plate and carried out its cooling up to Ò-12 Ê.

With the leakage system (10) in the chamber was setting the operating pressure

of the mixture Ð=10-5 Torr, the substrate was opening and begun the

process of film cryocondensation, controlled by double-beam laser

interferometer. Upon reaching the sample thickness of about 25-30 μm gas

filling was stopped and a pressure about Ð=10-8Torr was placed back

in the chamber. Next, the vibrational spectrum of the sample was measured,

whereupon IR spectrometer was installed at a frequency of observation and

within 30-40 minutes was measured interferometer signal at a constant

temperature equal to the condensation temperature Ò=16 Ê. Thus, the state of

the sample was analyzed over time at a constant temperature.

Further measurements were carried out by

two methods. In one case, was carried out the step heating of the sample by

0.5-1 degree with the measurement of the reflectance spectrum at a fixed

temperature. In the second case, was carried out the continuous heating of the

sample, the speed of which determined by the natural heat inflows to the

substrate with switched off microcryogenic machine. In this case, was measured

the IR-spectrometer signal at a fixed frequency in the vicinity of the

characteristic vibration frequencies of the water molecule. Changes in a given

signal are a reflection of transformations in the test sample.

3.Conclusions

Our studies have shown that in the process of co-condensation of methane and

water on the substrate at a temperature of T = 16 K, a two-component solid film

is formed. Measuring the vibrational spectra of the samples we have found a

little "blue" shift relative to the spectra of pure solid methane,

amounting to the value of the bending vibration of about 14 cm-1 for

CH stretching vibrations of approximately 5 cm-1. It is virtually

identical to the data for nitrogen and argon matrices, from which we can

conclude that the state of the methane molecule and its vibrational spectrum

are weakly dependent on the composition in the discussed mixtures.

At this stage of research we can make some assumptions regarding the status of

methane molecules in the "matrix" of water based on the comparison of

the thermal desorption curves and of thermograms of amplitude variations of the

absorption characteristic vibration frequencies of methane.In our view, it is

natural to assume that under these conditions cryoprecipitated methane in solid

solution with water can occure in three states. Firstly, it is actually a

condensed state, i.e. solid phase of methane. Secondly, the methane can be in

an adsorbed state. The role of absorbent is played by the amorphous solid water

(ASW). Those states are condition characteristics of water cryovacuum

condensates formed at T = 16 K [14, 15]. Thirdly, methane may be in a bound

state with the molecules of water forming clathrates. This, indeed, is the

subject of our study. In this paper we attempt to determine the temperature

ranges of these states, based on the properties of amorphous solid water ASW

and comparing obtained thermograms desorption and absorption amplitudes of

deformation vibrations of methane.

A. Drobyshev, A. Aldiyarov, K. Katpaeva, E. Korshikov, V. Kurnosov, D. Sokolov. 39 (8),

2. A. Aldiyarov, A. Drobyshev, E. Korshikov, V.

Kurnosov, and D. Sokolov. Physics of the Solid

State, Vol. 54, No. 7, pp. 1475–1479

(2012)

3.

P.

Jenniskens, D. F. Blake. Astrophys. Jour. 473,

1104-1113 (1996)

4. A. Aldiyarov, M. Aryutkina, A. Drobyshev, M. Kaikanov, and V. Kurnosov.. Low Temp. Phys, Volume: 35, Issue: 4, Pages: 251-255 (2009)

5. Talon C., Ramos M., Vieira S., Guello G.,

Bermejo F., Griado A., Senent M., Bennington S., Fischer H.,Schober H.

Low-temperature specific heat and glassy dynamics of a polymorphic molecular

solid // Physical Review. – 1998. – vol. 58,

2. – p. 745.

6. M.E. Fajardo and S. Tam., J. Chem. Phys. 115, 6807 (2001).

7. A.J. Tursi and E.R. Nixon, J. Chem. Phys.52, 1521 (1970).

8.

J.B. Paul, C.P. Collier, R.J.

Saykally, J.J. Sherer, and A.O. Keefe, J. Phys. Chem. 101, 5211 (1997).