Ýêîíîìè÷åñêèå íàóêè

Ñòàðøèé

ïðåïîäàâàòåëü Ðÿáèêèíà Å.Â., ñòóäåíò Ïîêóëü À.Í.

Ðîñòîâñêèé

Ãîñóäàðñòâåííûé Ýêîíîìè÷åñêèé Óíèâåðñèòåò, Ðîññèÿ

Changes in China’s Economic

In recent decades, many of Asia’s economies have

boomed.

Asia has made unprecedented strides in reducing

poverty and improving broad development indicators. The poverty rate fell from

55% in 1990 to 21% in 2010, while education and health outcomes have improved

significantly. Hundreds of millions of lives have been improved in the process.

And, looking ahead, Asia is expected to continue to grow at an average annual

rate of 5%, leading global economic expansion.

But today, the region is facing challenging new

economic conditions. With growth in advanced economies tepid, risk aversion

increasing in global financial markets, and the commodity super-cycle coming to

an end, the world economy is providing little impetus to Asian growth.

At the same time, China is moving toward a more

sustainable growth model that implies slower expansion. Given the growing links

between China and the rest of the world, particularly Asia, the spillover

effects are significant. Indeed, China is now the top trading partner of most

major regional economies, particularly in East Asia and ASEAN. New research by

the International Monetary Fund, to be published in next month’s Regional

Economic Outlook for Asia and the Pacific, suggests that the median Asian

country’s economic sensitivity to China’s GDP has doubled in the last couple of

decades. So China’s slowdown means a slower pace of growth across Asia.

Asia’s achievements in recent decades attest to the

hard work of the region’s people, as well as to the soundness of the policies

that many Asian governments have adopted since the late 1990s, including

improved monetary-policy and exchange-rate frameworks, increased international

reserve buffers, and stronger financial sector regulation and supervision.

Against this backdrop, the region attracted vast amounts of foreign direct

investment.

As trade links expanded, a sophisticated network of

integrated supply chains emerged, creating the conditions for Asia to become a

manufacturing powerhouse and, increasingly, an exporter of services as well.

More recently, thanks to strong policies and ample reserves, the region quickly

recovered from the global financial crisis. Asia also benefited during these

years from strong global tailwinds, including favorable external financing

conditions and the rapid expansion of the Chinese economy.

Amid this new testing reality now dawning in Asia, we

must not lose sight of the deep, and long term, structural challenges facing

the region. Populations are rapidly aging and even declining in countries like

Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Thailand, dragging down potential growth and

putting pressure on fiscal balances.

Income inequality is a further challenge. While

inequality has remained stable or declined in Malaysia, Thailand, and the

Philippines, it is rising in many parts of the region, most notably in India

and China (as well as other parts of East Asia). In many emerging markets and

developing countries, widespread infrastructure gaps persist, notably in power

and transport. And, elsewhere in the region – the small Pacific islands in

particular – vulnerability to the effects of climate change is increasing.

This shifting landscape calls for bold action on

several fronts. While the response will certainly need to be tailored to each

country’s specific circumstances, some recommendations could be helpful for

most countries:

· Because inflation remains low across most of the

region, monetary policy should remain supportive of growth in case downside

risks materialize.

· Exchange-rate flexibility and targeted

macroprudential policies should be part of the risk-management toolkit.

· Countries need to deepen their financial systems to

channel the large pool of domestic and regional savings toward financing their

development needs; closing the region’s infrastructure gaps, for example,

remains critical.

· Structural reforms, aided by fiscal policy, should

support the economic transitions and rebalancing, while boosting potential

growth and alleviating poverty.

The good news is that Asia, as demonstrated by its

strong performance in recent years, can meet these challenges and continue to

build upon the significant achievements of the past two decades. It has the

resources and the people; it has the buffers and resilience; and it has ample

opportunities for further trade and financial integration.

To discuss these challenges, the government of India

and the IMF are organizing the Advancing Asia conference in New Delhi on March

11-13, bringing together regional policymakers and thinkers. India, a bright

spot among emerging markets in these difficult times – indeed, the world’s

fastest growing major economy – is an auspicious place to hold this gathering.

Our mutual aim in convening with Asian policymakers is

clear and critical, for Asia and for the global economy: to ensure that growth

in Asia continues to be robust, sustainable, and inclusive, so that the region

remains a powerful locomotive for global growth.

Reaching the goal of 6.5-7% GDP growth will require

either a fudging of the figures or investment in projects of dubious worth. A

second train line to remote and mountainous Tibet is planned. Banks are being

leant on to juice up the economy. Credit is growing at twice the rate of

nominal GDP, in a country already overburdened by private debt. A big increase

in the money supply will put downward pressure on China’s currency, which in

turn will lead either to a rapid rundown in foreign-exchange reserves or a

devaluation.

In theory, China’s capital controls can ease the

pressure, by making it harder for money to leave the country. And the latest

figures suggest they are becoming more effective. Reserves dropped by just $29

billion in February, to $3.2 trillion, after three months of heavier falls. But

even if China can successfully police its financial borders, rapid credit

growth will fuel asset prices at home. Wary of the stockmarket, investors with

cash to spare see property as the safest bet. Unregulated online lenders are

helping them pile on leverage, skirting rules requiring minimum down-payments

on homes. There are worrying signs of a bubble in several big cities: house

prices in Shenzhen have risen by 53% in the past year.

Supporting a sagging economy with cheap money and tax

cuts is sensible. But China also needs to put in place the structural reforms

that will make such stimulus both more effective and less destabilising.

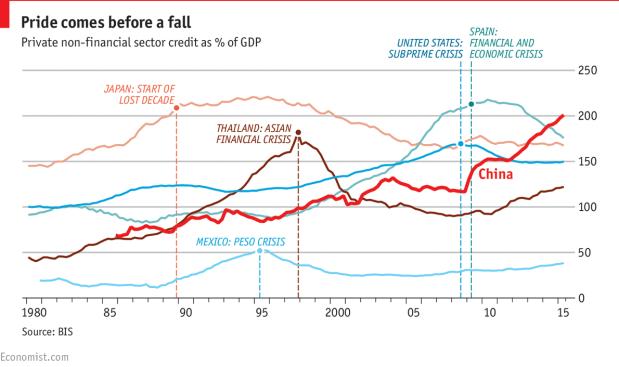

DEBT in China is piling up fast. Private debt, at 200% of GDP, is only

slightly lower than it was in Japan at the onset of its lost decades, in 1991,

and well above the level in America on the eve of the financial crisis of

2007-08. China’s binging borrowers seem to have run out of good investments.

The value of non-performing loans in China rose from 1.2% of GDP in December

2014 to 1.9% a year later. Some big firms are earning too little to service

their debts; instead, they are making up the difference by borrowing yet more.

The IMF reckons that

surging credit is “the single best predictor of financial instability”, but

China might be able to avoid a crisis. Very little of its debt is owed to

foreigners, and the government has room to borrow to cushion the economy

against loan defaults and failing banks. Yet when Chinese firms eventually flip

from borrowing to repaying their loans, growth will probably slow sharply. That could make

for difficult times for people in China, and in the rest of the world as well.

List of literature

2. http://www.ft.com/home/asia

3. Options, Futures, and

Other Derivatives (9th Edition) 9th Edition by John C. Hull