Òåõíè÷åñêèå íàóêè/ Àâèàöèÿ è êîñìîíàâòèêà

Dr Nickolay Zosimovych

Shantou University, Shantou, China

INCREASING THE ACCURACY OF THE CENTER OF MASS STABILIZATION OF SPACE

PROBE

Keywords: Space probe (SP), stabilization controller (SC), on-board computer (OC),

gyro-stabilized platform (GSP), propulsion system (PS), angular velocity sensor

(AVS), operating device (OD), space vehicle (SV), feedback (FB), control

actuator (CA), control system (CS), angular stabilization (AS), center of mass

(CM).

I. Introduction. In some cases, when using a control

system built according to the principle of program control (the "robust

trajectories" method) the efficiency of task solution is much influenced

by the accuracy of the spacecraft stabilization system in the powered portion

of flight. This concerns, for example, the trajectory correction phases during

interplanetary and transfer flights, when the rated impulse execution errors

during trajectory correction resulting from various disturbing influences on

the spacecraft in the active phase, greatly affect the navigational accuracy.

Hence, reduction of the cross error in the control impulse on the final

correction phase during the interplanetary flight, facilitates almost

proportional reduction of spacecraft miss in the "perspective plane".

For example, in some space probes (SP) like Deep Impact [1, 2] and Rosetta

missions [3, 4] reduction of cross error by one order during the execution of

correction impulse (for modern stabilization systems this value shall be ![]()

![]() results in

reduction of spacecraft miss in the "perspective plane" from 200 to

20

results in

reduction of spacecraft miss in the "perspective plane" from 200 to

20 ![]() Such

reduction of the miss accordingly

increases a possibility of successful implementation of the flight plan, as well

as the accuracy of the research and experiments conducted [5].

Such

reduction of the miss accordingly

increases a possibility of successful implementation of the flight plan, as well

as the accuracy of the research and experiments conducted [5].

The

Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) mission is scheduled to launch from the Tanegashima Space Center in September 2024. The spacecraft

will arrive at Mars in August 2025 and spend the next three years exploring the

two moons and the environment around Mars. During this time, MMX will drop to

the surface of one of the moons and collect a sample to bring back to Earth.

Probe and sample should return to earth in the summer 2029 [6].

Objectives: to

solve the task of significant increase in stabilization accuracy of center of

mass tangential velocities during the trajectory correction phases when using

the "rigid" trajectory control principle.

Subject of research:

The center of mass movement stabilization system in the transverse plane, which

is used during the trajectory correction phases.

In order the control actions could be created during the spacecraft

trajectory correction phase, a high-thrust service propulsion system with a

tilting or moving in linear direction combustion chamber shall be used.

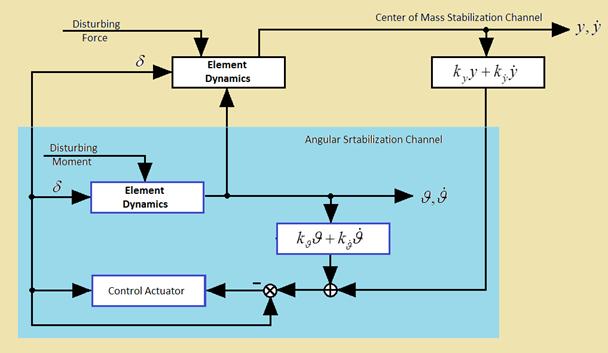

II. Content of the

Problem. Functioning

of the spacecraft movement stabilization channel in the transverse plane is

based on the feedback principle, and together with the spacecraft this channel

forms a closed deviation control system. We can consider two channels in this

control system: an angular stabilization channel and center of mass movement

stabilization channel (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Functional diagram of model

spacecraft stabilization

The angular stabilization channel facilitates angular position of the

spacecraft when exposed to disturbing moments. The center of mass movement

stabilization channel is to ensure proximity to zero of normal![]() and lateral

and lateral![]() velocities of

the spacecraft under the influence of disturbing moments and forces. In most of

the known (model) spacecraft stabilization systems [7-9] the control signal in

the center of mass movement stabilization channel is generated according to

proportional plus integral control law based on the measurements of tangential

velocity of the center of mass

velocities of

the spacecraft under the influence of disturbing moments and forces. In most of

the known (model) spacecraft stabilization systems [7-9] the control signal in

the center of mass movement stabilization channel is generated according to

proportional plus integral control law based on the measurements of tangential

velocity of the center of mass ![]() and its

integral-linear drift

and its

integral-linear drift ![]() In the angular stabilization channel, the control

signal shall be generated in proportion to the spacecraft deviation angle in

the transverse plane

In the angular stabilization channel, the control

signal shall be generated in proportion to the spacecraft deviation angle in

the transverse plane ![]() and the angular

velocity of the spacecraft rotation in this plane

and the angular

velocity of the spacecraft rotation in this plane ![]()

The required dynamic accuracy of

stabilization of tangential velocities in this system shall be achieved through

the choice of the gain in the stabilization controller ![]() If the

requirements to the accuracy of center of mass movement stabilization are

stiff, the coefficients

If the

requirements to the accuracy of center of mass movement stabilization are

stiff, the coefficients ![]() and

and ![]() shall be

necessarily significantly increased [7]. However, if these coefficients are

increased up to desired saturation, the system shall loose its motion

stability, and further improvement of the accuracy of the spacecraft center of

mass movement stabilization shall be impossible when this method of control is

applied. This can be explained by the fact that the increase in the gain values

in the center of mass movement stabilization channel results in improved

performance of the channel, and the frequencies of the processes occurring in

it become close to the frequencies of the angular stabilization channel, which

fact enhances interaction of these two

channels and makes it impossible to significantly improve the stabilization

accuracy of the spacecraft center of mass tangential velocities in the control

system concerned.

shall be

necessarily significantly increased [7]. However, if these coefficients are

increased up to desired saturation, the system shall loose its motion

stability, and further improvement of the accuracy of the spacecraft center of

mass movement stabilization shall be impossible when this method of control is

applied. This can be explained by the fact that the increase in the gain values

in the center of mass movement stabilization channel results in improved

performance of the channel, and the frequencies of the processes occurring in

it become close to the frequencies of the angular stabilization channel, which

fact enhances interaction of these two

channels and makes it impossible to significantly improve the stabilization

accuracy of the spacecraft center of mass tangential velocities in the control

system concerned.

To improve the correction accuracy, the following additional algorithm

shall be used in practice [9, 10].

The position of the steering control (turning PS) at the end of the previous

active phase shall be memorized and set in its original position before PS is

activated during next correction. The improvement of accuracy in this case

shall be achieved by partial compensation of the main disturbing factors:

eccentricity and thrust misalignment in the propulsion system already in the

initial moment of operation of the propulsion system. This algorithm is based

on the assumption that eccentricity and thrust misalignment in PS change

slightly towards the end of the active phase during the previous correction,

and PS setting before a new active phase sets in progress, ensures that the

thrust vector goes approximately through the center of mass of the spacecraft,

thereby considerably offsetting the disturbing moment. A similar algorithm was

applied in the stabilization system of the Apollo spacecraft [11].

It should be pointed out that the process of implementation of the

described algorithm is confronted by a number of challenges [5]:

·

Difference in disturbing factors

(moments and forces) during the previous and subsequent corrections results in

additional errors in the stabilization of the tangential velocities of the

spacecraft center of mass.

·

Due to the limited time of the active

phase, deactivation of PS during the previous correction may occur even before

the completion of the transition processes in the stabilization system, and as

a result, the system will remember the deviation of the steering control, which

was not final.

Besides introduction of additional control algorithms, there are other

ways to increase the accuracy of the center of mass movement stabilization. It

is a commonly known fact that one of the ways to achieve high accuracy in

automatic control systems, is to use the so-called invariant theory [12-14].

One of the problems inherent in the synthesis of invariant control

systems, is the ability for the implementation of such systems in most cases

through the use of the deviation control principle, as the simplest one and

most widely used in practice. The publications [15-18] consider the possibility

of constructing an invariant deviation control system with one adjustable

parameter including an inertial element and a servo control with feedback. The

general provisions of the invariant theory prove that no absolutely invariant

system can be implemented in this case because this requires that the circuit

with feedback should have an infinitely great gain.

As a rule, most invariant control systems are based on the use of the

information about external influences. Such control systems belong to the class

of combined regulatory systems. In particular, the combined systems constitute

the majority of invariant systems [19-25].

There is still another method to enforce implementation of invariance

conditions without application of combined regulatory techniques [26]. This

method is based on the dual-channel principle, which means that in order to

ensure the absolute invariance of some adjustable value towards external

influence, invariance with respect to the above influence should be ensured

between the point of influence application and the measuring point. To

implement such a system, it is necessary that two influence distribution

channels should be present in the controlled element.

In order to improve the accuracy of the synthesized algorithms, we

propose the application of self-configuring elements, which turn the operating

device and X-axis of the spacecraft at angles recorded at the end of the

previous active phase before a new active phase begins. The use of the above self-configuring

elements in the synthesized invariant algorithms produces the maximum effect in

increasing of the dynamic accuracy of tangential velocities stabilization as

compared to similar techniques in the existing systems. This is due to the fact

that the dynamic error of drift velocity in the synthesized algorithms, shall

be largely determined by the initial conditions of the transition process due

to the partial invariance of the algorithms proposed, which with the help of

the mentioned self-configuring elements, can approach the values corresponding

to the established mode as close as possible.

The publication provides analysis of stability of the synthesized

control algorithms, proves availability of stability margins in partially

invariant systems sufficient for practical implementation [5].

We propose an algorithm for selection of parameters of the stabilization

controller, which facilitates minimization of maximum error during

stabilization of the tangential velocity of the spacecraft center of mass while

ensuring adequate stability margins in the system.

Conclusion. The

publication provides analysis of stability of the synthesized control

algorithms, proves availability of stability margins in partially invariant

systems sufficient for practical implementation.

We propose an algorithm for selection of

parameters of the stabilization controller, which facilitates minimization of

maximum error during stabilization of the tangential velocity of the spacecraft

center of mass while ensuring adequate stability margins in the system.

References

1.

Deep Impact Launch. Press Kit, January, 2005, NASA,

USA.

2.

William H. Blume. Deep Impact Mission Design. Springler, Space Science Reviews, 2005, PP. 23-42.

3. Matt Taylor. The Rosetta mission, ESA, 2011.

4.

Verdant M., Schwehm G.H.

The International Rosetta Mission, ESA Bulletin, February, 1998.

5. Nickolay Zosimovych,

Modeling of Spacecraft Centre Mass Motion Stabilization

System. International Refereed Journal of Engineering and Science (IRJES), Volume 6, Issue 4 (April 2017), PP. 34-41.

6.

https://www.cosmos.esa.int/documents/653713/1000951/01_ORAL_Yamamoto.pdf/c0143f57-5863-46da-bc00-e32e88be08a6

- Yamamoto, M.-Y., Observation plan for Martian meteors by Mars-orbiting MMX

spacecraft. April, 11, 2017.

7.

Óïðàâëåíèå è íàâåäåíèå áåñïèëîòíûõ ìàíåâðåííûõ

ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ íà îñíîâå ñîâðåìåííûõ èíôîðìàöèîííûõ òåõíîëîãèé / Ïîä

ðåä. Ì.Í. Êðàñèëüùèêîâà è Ã.Ã. Ñåáðÿêîâà.

– Ì.: ÔÈÇÌÀÒËÈÒ, 2003, 280 ñ.

8. Ñòàòèñòè÷åñêàÿ äèíàìèêà

è îïòèìèçàöèÿ óïðàâëåíèÿ ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ: Ó÷. Ïîñîáèå äëÿ âóçîâ / À.À.

Ëåáåäåâ, Â.Ò. Áîáðîííèêîâ, Ì.Í. Êðàñèëüùèêîâ è äð. -

Ì.: Ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå, 1985. - 280 ñ.

9. Ñòàááñ Ã., Ïèí÷óê À., Øëþíäò Ð. Öèôðîâàÿ Ñèñòåìà ñòàáèëèçàöèè êîñìè÷åñêîãî

êîðàáëÿ “Àïîëëîí”. – Âîïðîñû ðàêåòíîé òåõíèêè, 1970, No 7.

10.

Ñïðàâî÷íîå ðóêîâîäñòâî ïî íåáåñíîé

ìåõàíèêå è àñòðîäèíàìèêå / Àáàëàêèí Â.Ê., Àêñåíîâ

Å.Ï., Ãðåáåíèêîâ Å.À. è äð. Èçàäàíèå

2-å, Íàóêà, 1976, 864 ñ.

11.

Robert G.

Chilton. Apollo Spacecraft Control Systems, NASA Manned Spacecraft Control

Houston, Texas, USA, 1965.

12.

Jan Willem Polderman, Jan C. Willems. Introduction to Mathematical

Systems Theory: A Behavioral Approach (Texts in Applied Mathematics), Springer;

2nd edition (October, 2008), 455 p.

13.

Spasskii R. A. Invariance of a system of automatic control,

Journal of Soviet Mathematics, June 1992, Volume 60, Issue 2, PP. 1343–1346.

14.

Bassam Bamieh, Fernando Paganini, Munther

A. Dahleh. Distributed Control of Spatially Invariant

Systems, IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, Vol. 47, No. 7, July 2002, PP.

1091-1107.

15.

Ðåïèí À.È. Òåîðèÿ

àâòîìàòè÷åñêîãî óïðàâëåíèÿ (Êîíñïåêò ëåêöèé), Ìîæàéñê, 2011, 150 ñ.

16.

Áåéíàðîâè÷

Â.À. Èíâàðèàíòíûå ñèñòåìû àâòîìàòè÷åñêîãî óïðàâëåíèÿ ñ ðåëåéíûì óñèëèòåëåì,

Äîêëàäû ÒÓÑÓÐà, ¹2 (21), ×àñòü 1, Èþíü 2010, ÑÑ.

70-73.

17.

Richard C. Dorf,

Robert H. Bishop. Modern Control Systems, Pearson, 12th edition, 807

pp.

18.

Silvia

Ferrari, Robert F. Stengel. Online Adaptive Critic Flight Control, Journal of

Guidance, Control, and Dynamics, Vol. 27, No 5, September-October, 2004, PP.

777-786.

19.

The

Electronics Engineer’s Handbook, 5ty Edition McGraw-Hill 19, 2005, pp.

19.1-19.30.

20.

Polderman J.W., Willems J.C. Introduction to the

Mathematical Theory of Systems and Control, 458 pp.

21.

Feron E., Brat G., Garoche P-L.,

Manolios P., and Pantel M. Formal methods for aerospace applications. FMCAD

2012 tutorials.

22.

Colon M, Sankaranarayanan S., and Sipma

H.B. Linear invariant generation using non-linear constraint solving. In Proc.

CAV, LNCS, PP. 420-432. Springler, 2003.

23.

Souris J.,

Favre-Felix D. Proof of properties in avionics. In Building the Information Society,

Vol. 156, pp. 527-535. Springler, 2004.

24.

Hennet J.C., Trabuco Dorea Carlos

E. Invariant Regulators for Linear Systems under Combined Input and State

Constraints. Proc. 33rd Conf. of Decision and Control (IEEE-CDC’94),

Lake Buena Vista, Florida USA, Vol. 2, pp. 1030-1036.

25.

Amaria Luca, Pedro Rodriguez, and Didier Dumur. Invariant sets method for state-feedback control

design, 17th Telecommunications forum TELEFOR 2009, Serbia, Belgrad, November 24-26, PP. 681-684.

26.

Gazanfar Rustamov. Invariant

Control Systems of Second Order, IV International Conference “Problems of

Cybernetics and Informatics” (PCI’2012), September 12-14, 2012, Baku, PP.

22-24.