Tåõíè÷åñêèå íàóêè/ Àâèàöèÿ è êîñìîíàâòèêà

Nickolay Zosimovych

Instituto Tecnólogico de Monterrey (Campus

Gualajara, Mexico)

INTEGRATED GUIDANCE SYSTEM OF A COMMERCIAL LAUNCH VEHICLE

In the article has been chosen and modeled the design objectives for an integrated guidance

system of a commercial launch vehicle with application of GPS technologies. Was set the conceptual design of an integrated

navigation system for the space launch

vehicle qualified to inject

small artificial Earth satellites

into low and medium circular orbits. The conceptual design of the

integrated navigation system based on

GPS technology involves determination of

its structure, models and

algorithms, providing the required accuracy and reliability in injecting payloads with

due regard to restrictions on

weight and dimensions of the system.

Keywords: Gimbaled inertial navigation

system (GINS), global positioning system (GPS), inertial

navigation system (INS), mathematical model (MM), navigation, pseudorange,

pseudovelocity, launch vehicle, self-guided system (SGS), Kalman filter, control loop, control system (CS), trajectory, boost phase (BPH), distributor, coordinate, orientation.

Introduction. A key tendency in the development of affordable modern navigation systems is displayed by the

use of integrated GPS/INS navigation

systems consisting of a gimbaled inertial

navigation system (GINS) and a multichannel

GPS receiver [1]. The

investigations show [2, 3], that such systems of navigation sensors with their relatively low cost are able to provide the required accuracy of navigation for a wide class of highly maneuverable objects,

such as airplanes, helicopters, airborne

precision-guided weapons, spacecraft, launch vehicles and recoverable orbital carriers.

Problem setting. The study of applications of GPS navigation technologies

for highly dynamic objects ultimately comes to solving the following problems [4]:

1. Creation

of quality standards (optimality criteria) for solving the navigation task

depending from the type of an object, its trajectory characteristics and restrictions on the

weights, dimensions, costs, and reliability

of the navigation system.

2. Choosing and justification of the

system interconnecting the

GPS-receiver and GINS: uncoupled, loosely coupled, tightly coupled (ultra-tightly coupled).

3. Making

mathematical models (MM) of an object's motion, including models of external

factors beyond control influencing object (disturbances). This requires to make two types of object models: the most detailed and complete one,

which will be later included in the model of the environment when simulating the operation of an integrated system, and a so-called on-board model, which is much simpler and more compact

than the former one, and which will be used

in the future to solve the navigation problem being a part of the

on-board software.

4. Making MM

for GINS in consideration of use of gyroscopes and accelerometers (i.e. it is required to make a model for navigation measurements supplied by GINS, taking into account systematic (drift) and

random measurement errors).

5. Making a model of the navigation field of GPS,

including system architecture, a method of calculating ephemeris of

navigation satellites in

consideration of possible errors, clock drifts on board the navigation satellites,

and taking into account conditions of geometric visibility of a navigation satellite on

different parts of the trajectory of a highly dynamic object.

6. Making a model of a multichannel GPS receiver, including models of code measurements (pseudorange and pseudovelocity) and, if necessary, phase measurements, including the whole range of chance and indeterminate factors beyond control, existing when such measurements are conducted (such as multipath effect).

7.

Choosing an algorithm to process measured data in an

integrated system in agreement with the speed-of-response requirement (the

possibility to process data in real time) and demanded accuracy in solving a

navigation task.

8. Creating an object-oriented computer complex for the implementation of the above models and algorithms with the objective to model the process of functioning of the integrated navigation system of a highly dynamic object.

Let's consider the

above objectives, having regard to peculiarities of the subject of inquiry,

namely a commercial launch vehicle, designed to launch payloads into low Earth

orbit (LEO) or geostationary orbit (GSO), in more

details.

Fig. 1. Launch vehicle Vega (Vettore Europeo di Generazione Avanzata, ASI&ESA) [5]

Within the framework of this study we shall consider a

light launch vehicle which has been jointly developed by the European Space

Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) since 1998 (Fig.1) [5]. It is qualified to launch satellites ranging

from 300 kg to 2000 kg into low circular polar orbits. As a rule, these are low

cost projects conducted by research organizations and universities monitoring

the Earth in scientific missions as well as spy satellites, scientific and

amateur satellites. The main

characteristics of the launch vehicle are given in Table 1. The launch vehicle Vega

[6] is the prototype of the vehicle under development.

The

planned payload to be delivered by the launch vehicle to a polar orbit at an

altitude of ~700 km shall be 1500 kg.

The launch vehicle is tailored for missions to low Earth and Sun-synchronous

orbits. During the first mission the light class launch vehicle is to launch

the main payload, a satellite weighing 400 kg, to an altitude of 1450 km with

an inclination of the orbit 71.500.

From the

standpoint of the problem concerned, namely the synthesis of the navigational algorithm of the space launcher in the proposed injection sequence we

are interested only in the first

factor, i.e. accuracy of lifting of the 3rd stage to the point of separation

4th stage. This

accuracy, other conditions being equal, is determined by the precision of solving a navigation task

in lifting the 3rd stage in

consideration of both components:

the center of mass and the velocity of the stage. They

predetermine the required impulse for the 4th stage

[7].

Thus, we may determine the main criterion of the accuracy of the navigation task in relation to the integrated inertial navigation system of the space launch vehicle: we need to ensure maximum accuracy in determining the position and velocity vectors of the 3rd stage of the launch vehicle in the exo-atmospheric phase

of the mission in the selected for

navigation coordinate system. Clearly, this accuracy, in its turn, other things being equal,

depends upon the accuracy of the initial conditions of travel of the 3rd stage,

or in other words, the accuracy of navigation on the previous atmospheric phase of the mission [1].

Consequently, in the case of the proposed injection sequence

the simplest and most obvious criterion for evaluation of the accuracy of

the synthesized system should be adopted.

It is required to ensure maximum accuracy in determining the vectors of position

and the center -of- mass velocity of the launcher during the flight of

the1st-3rd stages, i.e. in atmospheric and

exo-atmospheric phases of the mission. This

accuracy can be characterized by the

value of the dispersions posteriori

of the corresponding components of

the mentioned vectors [8].

Matherials and Methods. Now let's consider the possible integration schemes for GINS and GPS receiver with

respect to this technical problem

[9]. As it has been aforementioned, currently we can think

of three possible integration schemes as

follows [10-14]:

·

uncoupled (separated subsystems);

·

loosely coupled;

· tightly coupled (ultra-tightly coupled).

Uncoupled systems are the simplest option

for simultaneous use of INS and GPS receiver [15]. Both

systems operate independently. But,

as INS errors constantly

accumulate, it is necessary eventually to make correction of

INS according to data provided by the GPS

receiver. Creating such architecture

requires minimal changes to the hardware and the software [9].

In

loosely coupled systems GINS and GPS also generate separate solutions, but there

is a binding unit in which GPS-based measurements and GINS readouts make

assessment of the status vector and make corrections of data

provided by GINS [15].

The advantage of this

scheme is in high functional reliability

of the navigation system. The

drawback is in correlation of errors, arriving from

SGS to the input of the second Kalman filter and the need of strict synchronization

of measurements provided by INS and SGS [15].

In tightly coupled systems (Fig. 2) the role of the INS is reduced only to the measurement of the primary parameters of translational and

rotational motions. For this reason,

in such systems INS are only inertial

measurement units, and the GPS receiver is without own Kalman filter. In such a structure both INS and SGS

provide a series of measurements for a common computing unit

[15].

Fig. 2. Tightly coupled system using INS and GPS receiver

Tightly coupled systems are characterized by high accuracy

compared with aforementioned systems,

and the integrated filter makes it

possible to use all available GPS satellites

optimal way, but at cost of the

functional redundancy of the

system. Tightly coupled systems use the only "evaluator" (as a rule, the Kalman filter) that uses differences between

pseudoranges and/or pseudovelocities, calculated (predicted) by INS and measured

by Self-Guided System. Advantages of such a scheme are the following [6]:

· the

problem of measurement correlation is absent;

· there is

no need in synchronization of INS and Self-Guided System as just one clock generator is used;

· search and

selection of law quality measurements of pseudorenges.

The disadvantages of

closely coupled systems are the following [6]:

· the need

for special equipment for Self-Guided Systems;

· use of

complex equations for measurements;

· low

reliability because INS failure may result if failure of the whole system.

The later drawback can be eliminated by introducing a parallel Kalman filter only for Self-Guided

System [9].

Results and Discussion. The main factors that determine the structure and composition of the navigation

system are required accuracy

and reliability of navigation parameters

within the given limits on the weight, size, power consumption (in some cases - for the

time of the system development and operation security)

(Table 1). Besides, consideration should be given to:

·

types of objects;

·

cost of the complex;

·

service conditions;

· possibility of maintenance and repair.

Table 1

The main advantages of integrated systems

|

Factors |

Quality characteristic |

|

Accuracy |

substantially |

|

Weight |

decreasing by 30-70% |

|

Volume |

decreasing by 50-60% |

|

Power consumption |

decreasing by 25-50% |

|

Reliability |

increasing |

|

Redundancy level |

increasing by 50% and more |

|

Cost |

substantially |

Proceeding from the above information we may conclude that an integrated navigation system of future launchers should have a structure which, depending on the functionability of SGS receiver, shall allow operating in accordance with the algorithms both as an uncoupled and tightly coupled system. It should be

capable of processing coordinates

and velocities as well as pseudoranges and pseudovelocities.

The structure of the complex is to be open to information from other on-board navigation tools and external consumers of

navigation information. This may be done by introducing the corresponding

input/output ports.

With

regard to the above considerations, we propose the following structure of the integrated

complex:

· GINS – the

main system that provides self-sufficiency and reliability;

· GPS

receiver – a device correcting GINS

in latitude, longitude, altitude and velocity in three

velocity projection components;

· onboard

computer – carries out a full range of programs providing operation in various modes, in particular, it comprises a Kalman filter

algorithm.

Clearly, the first of the above schemes

using both GINS and

GPS receiver is not acceptable for our task, because here

the receiver is not used for calibration

(adjustment) of GINS during the mission by evaluating the drift component. As a result, in the absence of GPS-data errors of GINS grow at the same rate as in the absence of the receiver [6].

Next, each of the two following

schemes of interconnection (uncoupled and tightly coupled) have their advantages and

disadvantages with regard to the technical

problem in question. Indeed, by

using a loosely coupled scheme we

can implement evaluation

of GINS drift components and therefore in the absence of GPS-data, "departure" of GINS will be significantly compensated. Which means that the apriori rejection of a tightly coupled scheme as the most challenging to implement is not a sufficient reason. Indeed, if the flight conditions allow us to estimate the actual values of systematic errors in measurement

of and pseudorange and pseudovelocity,

the tightly coupled scheme allows us

obtain the highest possible accuracy of

navigation [6].

Thus, we conclude that in the present study it is appropriate to examine both schemes of

interconnection: tightly and loosely coupled, and based on the results of simulation, draw conclusions in favor of one of the possible solutions. Let us briefly examine the scientific and technical problems arising

when making the corresponding models and algorithms.

MM of spatial

motion of center of mass and relative to

center of mass of a solid launch vehicle

is well known and widely described in sources.

Mathematical

models of GINS are

currently also well described in sources, e.g. [17-21]. At the same time MM of GINS drift

depends essentially on the type of

gyro units and accelerometers

used in GINS. In other words, a so-called nonmodelable

constant is always present in the drift model. It ultimately

determines the possibility of GINS

alignment during flight. Because of apriori uncertainty of this component it is appropriate to select the parameters of the

shaping filter in such a way as to ensure the least impact on the accuracy of estimation. In other words, it is advisable in this case to receive a guaranteed result.

MM of

the navigation field created by the GPS and GLONASS systems, including the

visibility of individual satellites during the flight well characterized as

well and can be implemented as it is described in the source [15, 22].

Now we shall move on to the

analysis of the possible algorithms for processing navigation

information. Due to the specific nature of the set task that requires processing of navigational measurements

as soon as they are received, we will consider only the recursive modification of the following algorithms: Bayesian (and Kalman filter) or

recurrent modification of the least

square method, which do not require, as we know

an additional a priori information about

the state vector of the object. Thus,

measurements generated in GINS

enter with a relatively high

frequency (200 Hz) while the code

measurements from the receiver generally

enter with a frequency of 1 Hz

and the fact that GPS delay measurements may require special modifications of the recursive information algorithm.

Finally, essential is the choice of a model

predicting object's motion in the onboard algorithm. Moreover, generally there can be several different prediction models which will be used for different phases of flight: atmospheric and exoatmospheric.

Next, the different prediction models can be used when using loosely

coupled scheme of interconnection with the different rates of data entry from the GINS and

GPS receiver.

Finally, the

last aspect that we need to consider

in setting the technical problem in the present paper is

selecting an approach to the

shaping of an integrated navigation system for a space

launch vehicle with GPS technology. It is important to stress once again, as mentioned earlier, the term "shape"

will understand the structure,

composition, models and algorithms for integrated

navigation system [1].

Obviously that with regard to the variety of different physical nature of uncontrolled

factors having an effect within the framework of this problem, the nonlinear nature of MM of subject's motion and nonlinear relationship

between the results of measurements and

navigation components of the state vector, the only reasonable approach to solving the technical problems stated

above is the simulation

of the operation of the system to be shaped.

The above stated makes it necessary to create a special "tool"

that shall ensure the implementation of

the chosen approach to the solution of

the technical problem set. This tool is a computer system with a fairly simple interface

allowing, nevertheless varying interactively

source data and parameters of the models and algorithms for analyzing and modeling results presented

in graphic and numeric forms. Generally such a system must include two models: a model of

the environment and a model of a launcher board [6].

For its part, a model of the environment should include as much detailed model of the object, disturbances, and natural and artificial navigation fields.

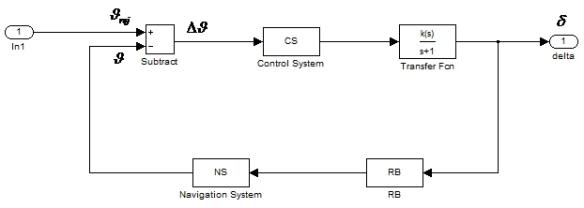

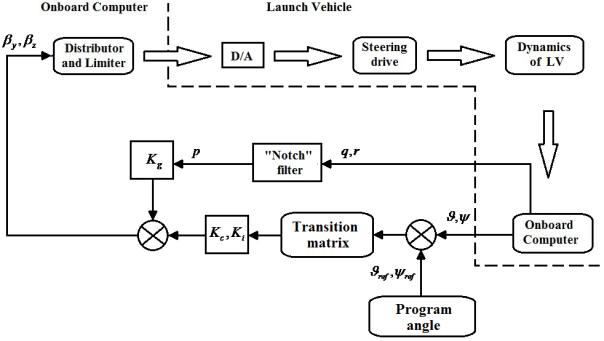

Model of a Control System for the Launch Vehicle. A control

system of the launch vehicle is designed to maintain the required (programmed)

trajectory parameters of the center of mass

and around the center of mass (Fig. 3) [16]. The launch vehicle under consideration has

only a control system of angular motion,

as its flight is conducted under

a fixed program changing the pitch angle in time [24].

Fig. 3. Control system of the

launch vehicle: CS – Control System;

RB – Rocket Booster; NS – Navigation System

Thus, control system of the launch vehicle in this

case is designed for testing

programmed orientation angles of the launch vehicle and attenuation of disturbing environmental influences (wind, disturbing forces and moments in the separation of stages of the

launch vehicle, etc.) [1]. Control loop

implements program control, i.e. system tends to nullify the difference between the current (variable)

and programmed (set in time) orientation angles of the launch vehicle.

Thus, the launch vehicle flies in a

so-called "fixed" trajectory [24].

Obviously, the initial information for the control loop is based upon measured values of the

orientation angles of the launch vehicle and the absolute angular velocity component

of the launch vehicle in a body-fixed frame [25, 26].

Physically and

logically the control system of the launch vehicle

is divided into stages, since,

first, different stages use

different controls (control

thrusters and movable nozzles), and

second, weight and inertial characteristics

of the launch vehicle vary significantly in different

phases of its flight which requires to change the parameters of the control loop integrally.

Besides, the control

system is divided by channels (longitudinal and lateral motion) despite the fact that in the first stage control of both channels is performed by the same controls [1].

The parameters of control loop were

chosen based on the following conditions:

in the boost phase (BPH) generally and in all

modes stability of all closed

loops in the control system (CS) must

be ensured. Accordingly, the

author has made programs changing the coefficients which correspond to the controllers of the control system ![]() [27].

[27].

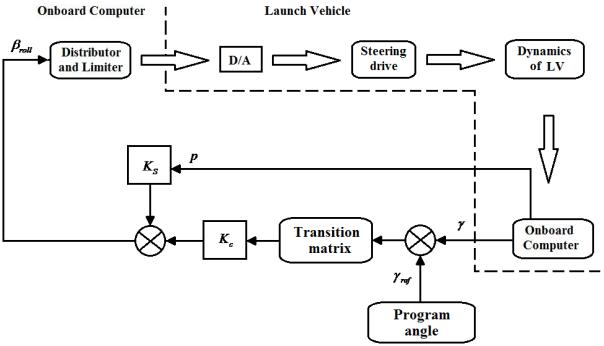

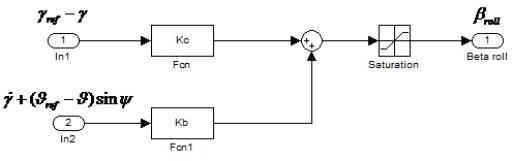

Accordingly, both loops close with

the help of special devices - distributor

and limiter of drive signals. Roll

control loop of the first stage

corresponds to the structure diagram

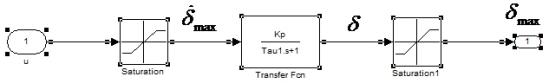

shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Structure diagram of the roll control loop for the first stage of the launch vehicle

The master

controller equation shall be the following:

![]()

Since angular velocities of the launch vehicle are determined in a body-fixed frame and deflections of controls are determined in the same coordinate system, the difference between the angles of orientation of the launch vehicle must be reprojected using the transformation matrix in the following form:

Then, the controller

equation may be as follows [24]:

![]()

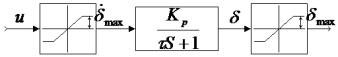

The structural

diagram of the limiter is given in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Structural diagram of the limiter

A simplified

mathematical model of the

drive is shown in the structural

diagram (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Simplified

mathematical model of the drive

Here: ![]() is an input

signal;

is an input

signal; ![]() is nozzle

deflection;

is nozzle

deflection;

![]() is a feedback

coefficient;

is a feedback

coefficient;

![]() is the time

constant of the drive;

is the time

constant of the drive;

![]() are permissible values of the angular velocity and the angle.

are permissible values of the angular velocity and the angle.

Pitch and Yaw control

System of the First and Second Stages. The pitch control loop and yaw control

loop have the same controllers in the first

and second stages. At the beginning the boost phase commands from the controllers are sent to the drives of the first stage only, and then, during

the simultaneous operation of the

first and second stages for a few

seconds commands from controllers are

sent to the drives of the first and second stages simultaneously, and after separation of the boosters of the first

stage - only to

the drives of the second stage.

Fig. 7. Structural diagram of pitch and yaw control loop of the first stage of the

launch vehicle

The pitch and yaw

control loops of the first stage correspond to the structural diagram shown in

Fig. 7.

Generation of a control signal for the

distributor and the limiter in

the first stage is described above.

A distributor is

absent in the second stage, and a limiter is used to limit command

signals by the maximum specified value of the deflection angle

of the nozzle:

![]()

pitch signal: ![]() if

if ![]()

![]()

yaw signal: ![]() if

if ![]()

![]()

A simplified mathematical model of the drive is presented in the

structural diagram (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Simplified

mathematical model of the first stage drive

Here: ![]() is an input

signal;

is an input

signal; ![]() is control

deflection;

is control

deflection;

![]() is a feedback

coefficient;

is a feedback

coefficient;

![]() is the time

constant of the drive;

is the time

constant of the drive;

![]() are permissible values of the angular velocity and the angle.

are permissible values of the angular velocity and the angle.

Pitch and Yaw Control

System of the Third Stage. A limiter is used

to limit command signals by the maximum specified value of the deflection angle of the nozzle:

![]()

pitch signal: ![]() if

if ![]()

![]()

yaw signal: ![]() if

if ![]()

![]()

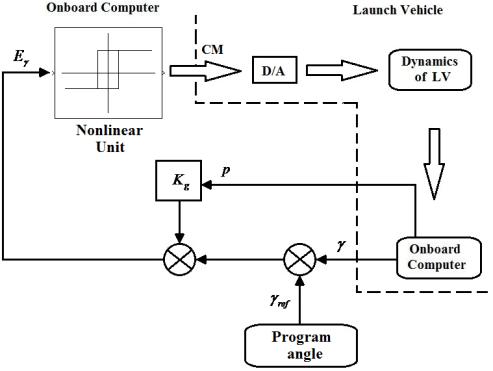

Roll Control System

of the 2nd and 3rd Stages. The main purpose of the

roll control loop on the second

and third stage is to stabilize

the roll movement of the launch vehicle and attenuate any

disturbances acting along the trajectory.

Unlike in the first two stages, stabilization is achieved by four specialized

liquid propellant engines installed diametrically in the third stage and

creating control moment pair wise, and not by deflection of nozzle of the solid propellant sustainer engine.

The roll control loop starts with

the moment of separation of the first

stage and runs until the moment of separation of the

third stage.

Fig. 9. Structural diagram of roll control loop of the 2nd and 3rd

stages of the launch vehicle

Block diagram of

the roll control loop for the 2nd and 3rd

stages of the launch vehicle is shown in

Fig. 9.

Conclusions

1. Based on the above, we have set a technical problem of the conceptual

design of an integrated navigation system for the space launch vehicle qualified to inject small artificial Earth satellites into low and medium circular orbits.

2. The conceptual design of the integrated navigation system based on GPS technology involves determination of its structure, models and algorithms, providing the required accuracy and

reliability in injecting payloads

with due regard to restrictions on weight and

dimensions of the system.

3. We have defined the sequence of essential

scientific and technical problems that lead to the solution of the major technical problem.

4. It has been demonstrated that it is appropriate to take a posteriori accuracy dispersion of the

position and velocity vectors of the

launch vehicle in phases of flight of I-III stages as a criterion of accuracy

of solving a navigation task.

5. We have made an analysis of possible models of flight and navigation measurements and identified

key potential difficulties in the process of their creation.

6. We have shown that the

main approach to solving the

technical problem is simulation

modeling with application of object-oriented soft.

References

1. Zosimovych

Nickolay. Integrated Navigation System for Prompting of the Commersial Carrier

Rocket. Information technology Conference for Academia and Professionals

(ITC-AP 2013), Sharda University, India, 19-21 April, 2013.

2. Flight instruments and navigation systems.

Politecnico di Milano - Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aerospaziale, Aircraft

systems (lecture notes), version 2004.

3. George M. Siouris. Aerospace Avionics Systems. Academic Press, INC

1993.

4. Kyu Sung Choi. Development of the commercial

launcher integrated navigation system the mathematical model, using GPS/GLONASS

technique. 52nd International Astronautical Congress, France,

Toulouse, 2001.

5. http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/ - Âåãà

(ðàêåòà-íîñèòåëü).

6. Nickolay Zosimovych, Anatoly Voytsytskyy. Disturbed Motion of the Launch

Vehicle with Integrated GPS/INS Navigation Systems. "Áúäåùèòå èçñëåäâàíèÿ – 2014" Proc. X

International Scientific and Practical Conference, Sofia, 17-25 February, Vol. 49. Technologies.

Physics, Sofia: Áÿë ÃÐÀÄ-ÁÃ, 2014, PP. 3-9.

7. Ëåáåäåâ À.À., Àäæèìàìóäîâ Ã.Ã., Áàðàíîâ Â.Í.,

Áîáðîííèêîâ Â.Ò. è äð. Îñíîâû ñèíòåçà ñèñòåì ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ. Ì.: ÌÀÈ,

1996, 224 c.

8. Bayley D.J. Design Optimization of Space Launch Vehicles Using a genetic

Algorithm, Auburn University, Alabama, 196 pp., 2007.

9. Zosimovych Nickolay. Selecting Design Objectives for an Integrated

Guidance System of a Commercial Launch Vehicle with Application of GPS

Technologies. The Open Aerospace Engineering Journal, 2013, Vol. 6, PP.

6-19.

10. Scherzinger, B. Precise Robust

Positioning with Inertial/GPS RTK Proceedings of ION-GPS-2000,

Salt Lake City UH, September 20-23, 2000.

11. Urmson, C., et al, A

Robust Approach to High Speed Navigation for Unrehearsed Desert Terrain,

Pittsburgh, PA, 2006.

12. Ds. Whittaker, W, Nastro, L., Utilization of Position and Orientation Data

for Preplanning and Real Time Autonomous Vehicle Navigation, GPS World,

Sept 1, 2006.

13. Daniel J. Biezad Integrated Navigation and Guidance Systems. AIAA

Education Series, 1999.

14. John F. Hanaway, Robert W. Moorehead. Space shuttle avionics system,

505 pp., 1989.

15. Óïðàâëåíèå è íàâåäåíèå áåñïèëîòíûõ

ìàíåâðåííûõ ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ íà îñíîâå ñîâðåìåííûõ èíôîðìàöèîííûõ

òåõíîëîãèé / Ïîä ðåä. Ì.Í. Êðàñèëüùèêîâà è Ã.Ã. Ñåáðÿêîâà. – Ì.: ÔÈÇÌÀÒËÈÒ,

2003, 280 ñ.

16. Nickolay Zosimovych, Anatoly Voytsytskyy. Design objectives for a

commercial launch vehicle with integrated guidance system. Novus

International Journal of Engineering&Technology, Vol. 3, No 4, 2014,

PP.7-28.

17. Boulade S., Frapard B., Biard A. GPS/INS Navigation system for

launchers and re-entry vehicles-development and adaptation to Ariane 5. ESA

GNC, 2003, pp. 57-64.

18. Kelly A.J. A 3D State Space Formulation of a Navigation Kalman Filter

for Autonomous Vehicles. CMU Robotics Institute Technical Report

CMU-RI-TR-94-19.

19. Alonzo Kelly. Modern Inertial and Satellite Navigation Systems. The

Robotics Institute Carnegie Mellon University, CMU-RI-TR-94-15, 1994.

20. Milan Horemuž. Integrated Navigation. Royal Institute of

Technology, Stocholm, 2006.

21. Cox, D. B. Jr. Integration of GPS with Inertial Navigation Systems.

Institute of Navigation, pp. 144-153.

22. http://satellite-monitoring.at-communication.com/en/secure/seu8800.pdf -

Satellite Monitoring and Intercept System SEU 8800.

23. Ôåäîñîâ Å.À., Áîáðîííèêîâ â.Ò.,

Êðàñèëüùèêîâ Ì.Í., Êóõòåíêî Â.È. è äð. Äèíàìè÷åñêîå ïðîåêòèðîâàíèå ñèñòåì

óïðàâëåíèÿ àâòîìàòè÷åñêèõ ìàíåâðåííûõ ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ. Ì.:

Ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå, 1977, 336 ñ.

24. Veniamin V.

Malyshev, Michail N.

Krasilshikov, Vladimir T.

Bobronnikov, Victor D.

Dishel. Aerospace vehicle control, Moscow, 1996.

25. Zelenkov A.A., Sineglazov V.M., Sochenko P.S. Analysis and synthesis

of the discrete-time systems. Kyiv: NAU, 2004, 168 p.

26. Jiann-Woei Jang, Abran Alaniz, Robert Hall, Nazareth Bedrossian,

Charles Hall, Mark Jackson. Design of Launch Vehicle Flight Control Systems

Using Ascent Vehicle Stability Analysis Tool. AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and

Control Conference, 08-11 August 2011, Portland, Oregon, USA. AIAA

2011-6652.

27. Îñíîâû

ïðîåêòèðîâàíèÿ ëåòàòåëüíûõ àïïàðàòîâ (òðàíñïîðòíûå ñèñòåìû). Ó÷åáíèê äëÿ

òåõíè÷åñêèõ âóçîâ / Â.Ï. Ìèøèí, Â.Ê. Áåçâåðáûé, Á.Ì. Ïàíêðàòîâ è äð. Ïîä ðåä.

Â.Ï. Ìèøèíà. – Ì.: Ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå, 1985. – 360 ñ.