Òåõíè÷åñêèå

íàóêè/6. Ýëåêòðîòåõíèêà è ðàäèîýëåêòðîíèêà

Ê.á.í.

Gabaev D.D.

A.V. Zhirmunsky Institute of Marine Biology, Far eastern Branch, Russian

Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia

The certain covering of conductors

can aid in problems

related

to room-temperature superconductivity

Keywords: coated metallic conductors,

room-temperature superconductivity

ABSTRACT: High – temperature

superconductors are required in many fields of modern technology. However

theirs widespread are prevent of complexity creation of low consistent

temperature for superconductors and work content theirs preparation and

operation. I measured the electrical

resistance of a number of metallic conductors, which I coated with materials of varying compositions and the

are found that when nichrome wires were covered with clean bone glue, there was

a conspicuous decrease in this resistance; with conductors containing iron

covered with clean bone glue, the resistance decreased to zero.

Introduction

Many useful mechanisms

and devices are not created because the problem of room - temperature

superconductivity is not solved. Till now superconductors should be cooled by

liquid nitrogen, that considerably complicates of their use. However my

analysis of the literature has allowed to conclude, that for occurrence of

superconductivity the low temperature is not obligatory. The following pieces

of evidence support the above hypothesis. the

discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in the mid-1980s1,2

overthrew the idea of temperature being a major factor in producing superconductivity.

it became clear that a great deal

depends on the composition of the doping used in such conductors1,2,3. studies

of the internal structure of cuprates and pnictides led researchers to the idea

that a superconductor is a hamburger, in which the electric current flows

through the “meat,” while the “buns” act as a supplier of electrons4.

The meat in those crystal sandwiches is represented by layers of copper oxide

or iron pnictides, composed of alternating layers of atoms. examination under high magnification of

the thin films that cover the crystal substratum revealed that the cuprate

coating consists of spiral ladders with a screw displacement; this structure

produced twisting in the lines of the magnetic field and facilitated high-temperature

superconductivity5. In the Cuo2 layers,

all the atoms were at almost the same level. However, in the FeAs layers, the arsenic atoms were situated above or below the iron

atoms, and four arsenic atoms, surrounding each iron atom, were located at the

tops of a tetrahedron6,7. The crystal lattices of recently

synthesized superconductors also have a tetragonal structure8,9,10.

Approaching the critical temperature for creation the tetragonal structure

appears to be an important factor in the superconductivity of pnictides6,7,8.

It appears likely that the pyramidal structure protects the conductor from the

noise produced by electromagnetic and sound waves, which cause oscillations in

the positive ions and thereby hinder the flow of electrons. It has long been known

that placing conductors within a pyramid increases the temperature at which

superconductivity appears11. a

number of studies have investigated the changes in the long-range

stripe-similar sequence at the critical temperature, which promotes the occurrence

of high-temperature superconductivity12. quasiparticle interference, in which particle-like behavior

disappears as a result of defects in a material, creates standing waves and

promotes superconductivity13. Based on the above observations, I conclude

that when a conductor is isolated from electromagnetic and sound waves, the

positive ions in the conductor’s crystal lattice go into a dormant state and do

not impede the flow of electrons. And I began to test various materials as a

covering for conductors.

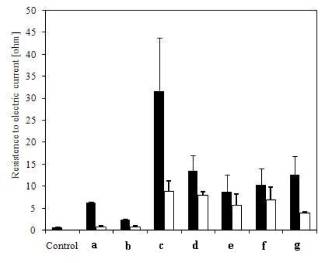

Results

It was found that in a 0.2-mm-diameter nichrome wire, which was coiled

into a spiral with a 7-mm diameter and covered with the experimental

composition, the electrical resistance did not decrease at ordinary room

temperature. The electrical resistance likewise showed no reduction when the

wire in the spiral was stretched to twice its original length. this was probably due to the magnetic

field generated by the electric current as it passed through the spiral wire.

It has long been known that magnetic fields destroy superconductivity4.

The experimental coatings decreased the resistance after the wire was wound

into large coils (100.0 mm in diameter) or folded in the form of a zigzag. With

the iron wire, the resistance decreased to zero (Fig.1).

The initial resistance of the water heater with the stainless

steel sheath was 6.3 ohms; after the sheath was coated with a 0.5-mm-thick

layer of bone glue, resistance in the sheath decreased to zero at room

temperature. The bone glue is an insulator. electrical

resistance in a 1.5-mm-diameter iron wire after the bone glue as well decreased

to zero at room temperature (fig.

2).

Thinning the layer of bone glue to a thickness of 0.05 mm caused the

resistance in the sheath to increase to 4.5 ohms. However, after the heater was

covered with Moment rubber glue and then allowed to dry, the resistance once

again decreased to zero. Placing ordinary magnets on the heater did not affect

its the electrical resistance. Five

days after the conducting the resistance measurements, I repeated the tests,

and the results I obtained were close to the initial ones.

There was a statistically

significant difference between the initial electrical resistance in the nichrome

wires and the resistance after coating: t (40)= 3.409; df = 39; p = 0.0015.

When the nichrome wire was covered with bone glue, the difference between the

initial electrical resistance in the nichrome wires and the resistance after

coating was as follows: t (11) = 2.32; df

= 10; p = 0.043. When the nichrome wire was covered with Moment rubber glue, the difference

between the initial electrical resistance in the nichrome wires and the

resistance after coating was as follows: t

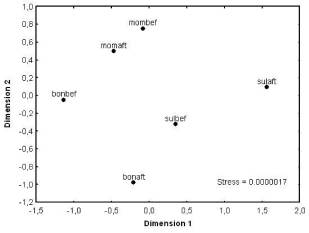

(10) = 2.88; df = 9; p = 0.018. Non-metric multidimensional scaling

analysis showed that the coating of bone glue and mixture of bone glue with Ca

(H2PO4)2 + CaCO3 produced the

greatest decrease in resistance in the nichrome wire (Fig. 3).

Under a scanning electron microscope, it

was evident that the various coatings showed defects in their structure; these

defects were 0.5–40.0 µm in size (Fig. 4). the

coating that provided the greatest decrease in resistance in the nichrome wire

(bone glue) had defects that measured about 1.0 µm.

discussion

High–temperature

superconductors are used in many fields of modern technology. However, several

obstacles prevent the widespread use of such superconductors. The first of

these is the complex issue of creating constant low temperatures that allow the

superconductors to function properly4. It has been reported that

superconductors containing iron (pnictides) require lower temperatures than

cuprates6.

There is an ongoing search

for new materials that can function as superconductors2,3; however, solving the problem of room-temperature

superconductivity has reached an impasse. practically

all existing inorganic substances have been subjected to trials as part of this

search, but no superconductivity at room temperature has been found14.

previous research efforts have

examined the phenomenon of superconductivity particularly with regard to the

doping used in the conductors1,2, and it has emerged that such a

doping should certainly not be metallic6,9. However, no tests have

been conducted on a coating similar to bone tissue.

I

covered metallic conductors with several kinds of coatings that had essentially

a similar composition to that of the cranial bones. My results showed that when

nichrome wires were coated, there was a significant reduction in the electrical

resistance. the greatest

reduction in resistance was observed when the wires were covered by clean bone

glue. When this coating was used on iron conductors, the electrical resistance

was reduced to zero.

Conclusion

In the present study, I have

demonstrated that when coated with bone glue, metallic conductors exhibit

considerably decreased electrical resistance at room temperature; when the

conductor contained iron, the resistance fell to zero. covering conductors with a thin layer of bone glue plus Moment

rubber glue imparted elasticity, resistance to impact, and stability to

moisture and magnetic fields without loss of superconductivity. the results of this study demonstrate

that it is possible to create a covering for conductors that decreases electrical

resistance to zero.

methods

To determine the possible influence

of a covering on the conductivity of metals, I covered metal conductors with

bone glue, which has been used by carpenters over the past century for gluing

wood. Bone is a calcified connective tissue, composed of cells within a solid

basic substance. Approximately 30% of this basic substance consists of organic

compounds, mostly in the form of collagen fibers, and the remaining 70% is

inorganic. The major inorganic component of bone is hydroxyapatite—Ca10

(PO4)6 (OH)2, but bone also contains various

amounts of sodium, magnesium, potassium, chlorine, fluorine, carbonates, and

citrates15. To determine the optimum coatings for the conductors, I

tested several compounds, including pure bone glue.

Instruments. For the

conductors, I used mostly nichrome and iron wires and also a foreign-made

immersion water heater with a stainless steel sheath (Weltor, Inc.). To measure

the resistance of the conductors, I utilized a household multimeter, DT-831

(ASD-Electro, Inc.) with a range of 200 ohms and resolution of 0.1 ohm. The conductor

coatings: pure bone glue; a dried mixture of superphosphate—Ca(H2PO4)2—and

chalk (CaCO3); a mixture of bone glue and CaCO3 + Ca (H2PO4)2;

a mixture of bone glue and superphosphate—Ca (H2PO4)2

were examined using a scanning electron microscope, EVO-40 (Carl Zeiss, Inc. germany)

Making bone glue

and mixtures. I made the pure bone glue coating using a thermostatic water bath (in

capacity with water capacity with glue and water is placed) by fusing bone glue

granules (bone glue, Usolsk Glue Factory, Russia) in

water at a weight ratio of 1:1 and at a temperature of 65–70°Ñ. The bone glue

mixtures were produced using the thermostatic water bath by mixing the bone

glue with salts or Moment rubber glue (produced of Henkel AG & Co. KGaA, germany).

Coating variants. First, the

resistance of 0.2-mm-diameter nichrome wire was measured. This wire was then

dipped into the following: (1) Moment rubber glue; (2) bone glue, which had

been melted in the thermostatic water bath; (3) humidified superphosphate—Ca (H2PO4)2—which

was mixed with the melted bone glue in the proportion of 50:50; (4) a mixture

in which three-quarters of the volume was CaCO3 + Ca (H2PO4)2

and one-quarter was melted bone glue; (5) a mixture in which three-quarters of

the volume was melted bone glue and one-quarter was Moment rubber glue. The

pieces of wire were immersed in the glue for no longer than one minute.

Resistance was measured in a 1.5-mm-diameter iron wire as well as in the water

heater, in which the diameter of the stainless steel sheath was 4.0 mm. Then,

the pieces of wire were immersed in the melted bone glue. After being removed

from the glue, the conductors were air-dried for six hours, following which

their resistance was measured. After removal from the water bath, the thickness

of bone glue at water heater was 0.5 mm. I then decreased the thickness of the

bone glue layer to 0.05 mm by immersion in the hot water. After drying the

conductor again, I measured the resistance of the sheath, then dipped the

conductor in the Moment rubber glue, dried it, and again measured the

resistance. I then attached several household magnets to the sheath and

measured the resistance.

Statistics. Data were analyzed using the

Statistica statistical package

(6.0 Version). The results were expressed as means and with a 95% confidence

interval. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to analyze the normal

distribution of the variables (p <

0.05). The data followed a normal distribution and were therefore analyzed

using parametric tests. Student’s t test

for dependent samples was utilized to assess the differences in the resistance

of electric current in the nichrome wires before and after the coverings were

applied. For graphical representation of the data, non-metric multidimensional

scaling ordination was carried out using the Bray-Curtis distance. before calculation, the data were

transformed according to the method adopted by16. For each variant, I coated 5–11

nichrome wires. In all, 40 wires were employed.

REFERENCES

1. Gerber, C., Anselmetti,

D., Bednorz, J.G., Mannhart, J., and Schlom, D.G.,

1991. "Screw dislocations in high –Tc films", Nature, vol. 350, pp. 279-280.

2. Hawley, M., Raistrick, I.D.,

Beery, J.G., Houlton, R.J., 1991. "Growth

mechanism of sputtered films of Yba2Cu3O7

studied by scanning tunneling

microscopy",

Science, vol. 251, pp. 49-51.

3. Amato, I., 1991. “Spiral forest” may hold clue to thin-film superconductivity",

Science, vol. 251, pp. 1564-1565.

4. Collins, G., 2009. "Clue from iron". V mire nauky, vol. 10, 60-67.

5. Garwin,

L., 1991. "Whorls upon whorls".

Nature, vol. 350, 277.

6. Kamihara, Y., watanabe, T., Hirano, M., and Hosono H.,

2008. "Iron-based

layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs

(x=0.05-0.12) with T0 = 26K", Journal

American

Chemical Society, vol. 130, pp. 3296-3297.

7. Matsuishi, S., Inone., Nomura T., Yanagi H., Hirano

M., and Hosono H., 2008 .

"Superconductivity induced by co-doping in quaternary

fluoroarsenide

CaFeAsF." Journal American Chemical

Society. vol. 130, pp. 14428-14429.

8. Imamura, N.,

Mizoguchi, H., and Hosono H., 2012. "Superconductivity in

LaTmBN

and La3Tm2B2N3

(Tm = transition metal)

synthesized under high

pressure".

Journal American Chemical Society. vol. 134, pp. 2516-2519.

9. Scheidt.

E-W., Hathwar, V.R., Schmitz, D., Dunbar, A. et al., 2012.

"Superconductivity

at Tc = 44 K in LixFe2Se2(NH3)y".

Europe of Physics Journal

B. vol. 85, pp. 279–283.

10. Engelmann, J., Müller, K.H, Nenkov, K., Schultz,

L., et al., 2012.

"Metamagnetic effects in epitaxial BaFe1.8Cr0.2As2 thin films".

Europe of

Physics Journal B. vol. 85, pp. 406-409.

11. Gatsunaev, N., 1999. "Rectification of

space". Be sound. vol. 9, pp. 96-99.

12.

Daou, R., Chang, J., LeBoeuf, D. Cyr-Choiniére, O. et al., 2010. "Broken

rotational symmetry in the pseudogap

phase of a high-Tc

superconductor".

Nature. vol. 463, pp. 519-522.

13. Moler, K.A., 2010. "How the cuprates hid their

stripes". Nature. vol. 468, 643

-644.

14. Comarov, S.M., 2012. "Superconductor".

Chemistry and life. vol. 4, pp. 26-29.

15.

Taylor, D.J., Green, N.P.O., Stout, G.W., 2010. "Biological Science"

1&2

(Ed. R.Soper). Moskow

16. Clarke, K.R. & Green, R.H., 1988. "Statistical design and

analisis for a

“biological

effects” study. Marine Ecology Progress Series. vol. 46, pp. 1-3.

Figure 1. Variations in the electrical resistance

(ohms, 20°C) of conductors with various coatings. The control instrument

reading in the experiments was with the absence of a conductor. (A) Resistance

in the 4.0-mm-diameter sheath of the water heater before (black) and after

(white) coating with bone glue; (B) resistance in a 1.5-mm-diameter iron wire

before (black) and after (white) coating with bone glue; (c) resistance in a 0.2-mm- diameter

nichrome wire before (black) and after (white) coating with bone glue; (d) resistance in a 0.2-mm- diameter

nichrome wire before (black) and after (white) coating with Moment rubber glue;

(e) resistance in a

0.2-mm-diameter nichrome wire before (black) and after (white) coating with a

mixture of bone glue and Moment rubber glue; (f)

resistance in a 0.2-mm-diameter nichrome wire before (black) and after (white)

coating with a mixture of salts—Ca (H2PO4)2 +

CaCO3—and bone glue; (g)

resistance in a 0.2-mm-diameter nichrome wire before (black) and after (white)

coating with a mixture of superphosphate—Ca(H2PO4)2—and

bone glue.

Figure 2. Measuring electrical resistance (ohms, 20°C)

in a conductor containing iron. (a) The control instrument reading in the

experiments was with the absence of a conductor; (b) electrical resistance in

the sheath of the water heater before the covering was applied; (c) electrical

resistance in the sheath of the water heater after the bone glue was applied;

(d) electrical resistance of the covering; (e) electrical resistance in a

1.5-mm-diameter iron wire before the covering was applied; (f) electrical

resistance in a 1.5-mm-diameter iron wire after the bone glue was applied.

Figure 3. Non-metric multidimensional scaling

ordination analyses of electrical resistance in the nichrome wires before and

after the different coatings were applied. Bonbef = befor covering of

bone glue, bonaft = after covering of bone glue, mombef = befor covering of Moment

rubber glue, momaft = after covering of Moment rubber glue, sulbef = befor

covering of a mixture of salts and bone glue, sulaft = after covering of a

mixture of salts and bone glue.

Figure 4. View of the coatings at high magnification. (a) The pure bone

glue had cavities owing to microbubbles of air; (b) dried salts—Ca (H2PO4)2

+ CaCO3—obtained by mixing with water under carbon dioxide aeration

show no structural disturbances; (c) the mixture of bone glue and salts—Ca (H2PO4)2

+ CaCO3—displays disturbances in its structure; (d) the mixture of

bone glue and superphosphate—Ca (H2PO4)2—had

disturbances in its structure.