Òåõíè÷åñêèå íàóêè/ Ãîðíîå äåëî

Ystykul

Karagoz Abubakirovna

Kazakh National Research Technical University after K.I.Satpaev,

Kazakhstan

Eugene

Levin

Michigan

Technological University, USA

Seredovich Vladimir Adolfovich

Novosibirsk State University of Architecture and Civil Enginering

Blagoveshenskyi Viktor Petrovich

Institute of geography Republic of Kazakhstan

TECHNOLOGY OF MEASURING OF AVALACHE SLOPES WITH USE OF TERRESTRIAL LASER

SCANNING FROM CIS COUNTRY VIEW

Introduction

Humans have had a great interest in avalanches since

ancient times, back when they frequently caused loss of life and livestock,

destruction of houses, etc. However, people were not able to discover the

nature of, and especially how to control avalanches, in those days. While many

troubles have been caused by avalanches, a complete avalanche disaster

inventory has yet to be created. The death records of avalanche victims have

been retained in the annals, manuscripts, books and human

memory.

The first mentions of avalanche disasters are found in

ancient descriptions of the campaigns of Alexander of Macedon in the mountains

of Central Asia and over the Hindu Kush into India [1].

The Alps is home to the longest record of avalanche

disasters, with written evidence from the antique and the early Middle Ages.

The first genuine medieval document reporting a death due to avalanche was part

of the retinue of Bishop Rudolph, Christmas in the year 1129 sent to Rome

through the Great St. Bernard [2]. The

Russians had to deal with avalanches in the Alps too. The army under the

command of A.V. Suvorov was going from Italy to Switzerland in the autumn of

1799. The army suffered minor casualties from avalanches at the St. Gotthard

pass and in narrow mountain valley on the way to devil's bridge. There is a

monument devoted to Suvorov's soldiers not far from devil's bridge, in an

alcove, carved into a steep mountain slope. Avalanches overlap it every winter.

In the twentieth century, the largest avalanche

disaster occurred again in the Alps during the First World War, on the

Austro-Italian front. According to the subsequent estimates six thousand

soldiers died from avalanches, more than people that’d died from the result of

military action [3]. Avalanche disasters are not the privilege of the Alps in

Europe. Lists of victims have been maintained in Iceland, Norway, Bulgaria and

other countries. However, the Alps remain as the primary location where

avalanches occur. One of the most horrible disasters happened in the French

Alps in 1970: the avalanche that struck the hotel in Val d'isere killed about

two hundred tourists and the other one pulled down the health resort for

children near Saint-Gervais, burying 80 people - children and staff [3].

Avalanche danger area

covers 124 km2 [4,5] in the mountainous regions of Kazakhstan. The

volumes of the avalanches in the area can reach 1 million square meters. Human

settlements, ski resorts and roads are threatened by avalanches. Eighty seven

people died in avalanches within the territory of Kazakhstan over the past 64

years. Mostly tourists such as climbers and skiers face the threat of

avalanches. Forecasting avalanches, preventive descents and defenses are used

as avalanche protection policies.

Neglecting the avalanche danger can lead to quite

severe consequences and significant destruction of infrastructure, and cause

human casualties. Therefore, research on the identification of avalanche sites

is very important. One of the avalanche areas in Kazakhstan is Ile Alatau

(Fig.1) and Altay [4].

There are avalanche areas along highways

Ust-Kamenogorsk – Zyryanovsk , Ust-Kamenogorsk – Samara and on the railway Ust-Kamenogorsk

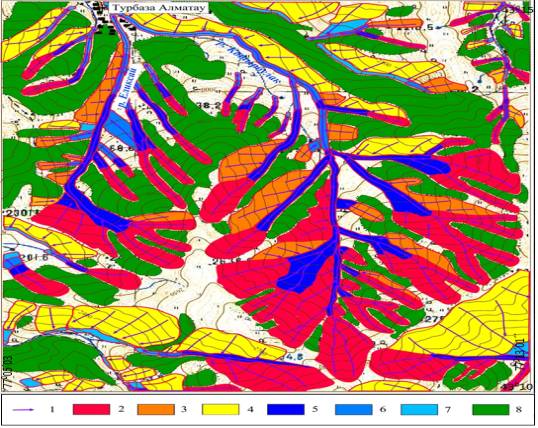

– Zyryanovsk in Altai. By the ski resorts of Chimbulak, Almatau (Fig. 2), the

Akbulak, the rink Medeu, the road through the valleys of the rivers Bolshaya

and Malaya Almatinka, Esik and Turgen. Marked hiking trails and climbing routes

are also threatened by avalanches in the Ile Alatau mountains. The number of

avalanche areas which cause danger will be increased in connection with the construction of new ski resorts. A major

ski resort of international class going by the name of "Kokzhailau " is

planned to be built for the winter Universiade close to Almaty in 2017.

Scale - 1: 25 000

Figure 1. Fragment of map of avalanche hazard in

Almatau

1

– avalanche road: less than 1

– 10 year; 2 –

before 10 till 50

year; 3

–more than 50 year; 4 –less than 10 year; 5

–before 10 till 50 year; 6 – less than 50 year; 7

–forest; 8 – road of avalanche;

9 – watershed; 10

– house

Three methods of research are used to explore and

describe avalanches, as well as to identify unhazardous avalanche areas: 1)

forwarding; 2) map 3) interpretation. Experience in the application of these

methods showed their advantages and disadvantages. Below is the examination of

each of these methods.

Expeditionary

method. The essence of this method is that the expedition is included to study

the area which charts avalanche hazard maps and avalanche cadaster according to

geomorphological, geobotanical and other characteristics. To carry out an

expedition is preferred in the spring or summer, because in winter the traces

of avalanche activity of the past years are hidden under the snow. It is

necessary to collect all the published information about previous avalanches in

the area prior to beginning the field work for choosing the topographic base in

meeting the practical goals of the expedition

Depending on time of the year field work occurs, the

expedition is equipped with appropriate equipment, food and uniforms. Based on

the information collected under this program an avalanche inventory is compiled

and appended to the map of avalanche danger, which is based on this topographic

base. Mapping avalanche risk using this method over large areas has a number of

disadvantages: the high cost of conducting field research; large complexity;

the difficulty of defining the boundaries of the catchment and ways of

avalanches.

The cartographic

method. The core of this method lies describing of the paths of avalanches and

avalanche catchment areas in the analysis of topography according to the

topographic maps. The cartographic method has the advantage compared with the

method of surveying, namely: 1. possibility of accurately defining the area of

catchment and its nature, the paths of avalanches, slope angles and slope etc.,

which is very important for calculations of possible impact force and distance

of snow avalanches. 2. Cost effective. The disadvantages of cartographic method

include: the impossibility of the survey in nature, as there are no changes on the map in the study area that occurred

after the release of those topographic maps; the impossibility of obtaining by

the remnants of snow cornices data on the nature of snow accumulation and

direction of the prevailing winds [6].

Aerial method. In addition to traditional

techniques, investigations of avalanche zones may also includes aerial methods.

Above ground methods include aerial photography and laser scanning (altimetry),

used usually in combination. Airborne methods of monitoring objects have a

number of advantages over spaceborne: high precision products, adjustability of

equipment and shooting options; partial or complete exclusion of works on

geodetic substantiation; high automation level; the possibility of technical

and economic planning with the whole complex of aerial surveys.

It is

necessary to formulate the organizational and economic aspects on the use of

manned aerial systems for monitoring

small areas of avalanche sites.

1. The cost of equipment for a

comprehensive aerial survey and data processing programs is quite high and

ranges from 1.5 to 2 million. Only large organizations are able to purchase and

use such equipment, those specializing in high-volume supply of information about remote sensing.

2.

The weight

of the navigation and airborne radar equipment (lidar) together is 200 kg or

more, which requires to be adapted for shooting aircraft (An-3, Cesna, etc.) or

helicopters (Mi-8T, etc.).

3. The use of manned equipment

assumes the availability of a well-developed field infrastructure: airfield,

depot and equipment maintenance, certified pilots, dispatcher and maintenance

personnel.

4. Obtaining and processing large

amounts of information leads to the creation of separate structural units:

mapping and surveying teams, groups, post-processing of survey data. Again,

this is only available for large specialized organizations.

Costs

of narrow strip of avalanche site laser scanning is significantly higher than

just a simple area scanning. Therefore, to use ALS on extensive grounds and

terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) on the local level is ultimately advised per

[7].

The

analysis of existing methods for modeling snow avalanches has shown that the

majority do not meet our practical needs. Low adequacy of physical/mathematical

representation of the avalanche, description in nature, and the low accuracy of

prediction. can be included as disadvantage of these existing methods. Some

methods cannot be implemented in particular conditions. Therefore, nowadays

identification of appropriate and accurate methods of modeling and forecasting

and analysis of snow avalanches is highly important.

The proposed method for modeling and forecasting snow avalanches can

determine the area, speed, and power of avalanches with high accuracy. For

example the software RAMMS, developed by the Swiss Institute of Snow and

Avalanches, is highly adequate in terms evaluating the physics of avalanches

[8].

The second order dynamics equation forms the basis for numerical

solutions. The height and speed of the snow flow is calculated on specially

designed digital three-dimensional terrain models [8]. Important survey

information is displayed while using the program In this model, the resistance

to the flow of the snow is taken in two types: power dry Coulomb friction with

coefficient µ, and the forces are proportional to the square of the speed of

movement of the snow mass, c the coefficient ξ. The frictional resistance

will be:

![]() (1)

(1)

ρ - the density of the stream;

g– free fall acceleration;

à is the average angle of the

slope in the given point;

H– the height of the stream;

U– flow velocity (speed).

This

model is best suited to describe the movement of very large avalanches

consisting of dry snow. At the same time, RAMMS is not capable of describing

wet avalanches and those of small volume. The authors suggest that a small

avalanche can be modeled by increasing the values of the coefficients µ and

ξ, but this requires pre-setting models. An additional disadvantage of

this model is that the movement of snow is not described at the avalanche

front, in the field of small moving mass, and large coefficients of resistance.

Therefore,

currently searching accurate, convenient methods of modelling, forecasting, and

analysis of snow avalanches is of high importance [8].

In snow and

avalanche research, terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) is used increasingly to

accurately map snow depths over an area of several km². Laser scanners

emit a pulse of light in the near-infrared spectrum. The pulse hits the terrain

or snow surface and is reflected. A photodiode in the scanner detects the

returning pulse, and determines the distance to the target from the travel time

of the pulse. The data from the reflected pulses are saved in a point cloud in

the scanner’s internal coordinate system. When the exact global position of the

laser scanner is known, and three translational and three rotational parameters

exist, the point cloud can be registered in a global coordinate system (Prokop,

2008). Prokop (2008), Prokop et al. (2008), and Grünewald et al. (2010)

report mean deviations between TLS data and reference tachymetry measurements

of 0.04-0.1 m for target distances reaching 500 m, depending on the conditions

and the laser used [9].

We used TLS

snow data to obtain precise quantitative information about snow depths and snow

redistribution. These data are derived by subtracting rasters from different

scan campaigns. Then we correlated the snow depth and distribution data with

the results of the terrainbased parameter and also compared the measured

pattern of snow redistribution with windfield simulations[10, 11].

Active

implementation and practice of TLS in various studies have shown highly

accurate output results, quick shooting and processing, and fusion of new

survey data with traditional methods [9].

The

technology of TLS is an effective tool for modeling and the subsequent analysis

of morphological properties of micro - and nanorelief and reliefoids (snow

cover, vegetation). High-precision digital elevation models allow for

proceeding to a qualitatively new level of morphological analysis [12].

Morphometric analysis

of topography is the base of investigation (DEM). To identify potential areas

of origin of avalanches the following criteria is selected: absolute and

relative heights; slope; curvature in plan; the minimum area of the zone of

origin; maximum unit of avalanche nonhazardous zone within avalanche hazardous

territory.

Figure

3. The algorithm of automated selection of avalanche hearth with the use of

morphometric analysis of the relief

Technological scheme of TLS-

1. Technical project planning.

2. Reconnaissance of the area. A rational way of creating and thickening

survey ground takes into account the specific conditions of the area [13]. The

location of the scanner and the placement of targets are outlined. The deadline

of the work is clarified. We have chosen the center of origin of avalanches on

the mountain slope and the installation location of the scanner (Fig. 5). The

first survey was held on 05 A5pril 2015 when there was snow cover. The second survey

was carried out on 02 July 2015 without snow.

1. Compilation scanner survey preparation.

2. Three-dimensional

Terrain Laser Scanning.

1) Installation of the scanner

onto a projected point with a tripod, the height is set to ensure maximum

coverage of the area of interest in one scan (Fig.6)

2) Special stamps spread around the scanner, which show the points of

operating survey object

3) Determination of the coordinates of the centers of special grades

from the basic reference points of the network

4) Scanning of the terrain and objects around a point of scanner

position

5) Identification and determination of approximate coordinates of the

centers of special grades to further quick determination of their position on

the scan

6) Scanning of special stamps with maximum resolution

7) Moving the scanner to the next scan point and repeating the steps

1-6.

Figure 5. Installation of the total station and scanner to projected point on a

tripod

Laboratory work.

Terrestrial laser scanning data can

be used to create a three-dimensional vector model of objects[15].

Data processing of laser scanner

data is aimed at obtaining high-quality digital terrain models and their

derived digital elevation models. The existence of such models is a

prerequisite for the development of analytical tools, oriented on the

investigation of surface geometry through a number of formalized procedures.

According to the DEM the depth, cross section, height, volume, and speed of

avalanches is determined and the potential to predict an avalanche is possible.

The terrain model is mapped with orthophoto imagery and can be modified based

on the identified errors [15].

Results.

Digital terrain modeling: digital

elevation models (DEM) is one of the powerful and pervasive GIS functions.

Under a DEM (digital elevation model) or DTM (digital terrain model) ) it is

commonly assumed that representations of three-dimensional objects are in the

form of three-dimensional data comprising many of the elevations and Z-samples

at the nodes of a regular or irregular network or a set of records of contour

lines or other structural lines [12].

Therefore,

the concerns of high-precision monitoring of avalanche sites using TLS can be

solved. A practical confirmation of the calculations is necessary. A Land-based

survey of hazardous glacial processes in the highlands is currently taking

place mainly at local areas with a limited observation period.

The issues of exploitation NLS systems: certification and registration

of TLS, obtaining permits for filming, security and insurance photography are

not considered in the article.

References cited:

1.

Kanonnikova

E.O., Philosophy- historical aspects of becoming and development of avalanche

as sciences, Modern problems of science and education). – 2014. -¹6. Page 45

(in Rus)

2.

Lossev

K.S. Po sledam lavin (On tracks avalanches). L: Gidrometeoizdat, 1983. Page 134 (in Rus)

3.

Tverdyi

A.B. ,The dangerous natural

phenomena are in mountains // Collection of scientific works KIMPiM ¹1). Krasnodar, 1999, page 34-57. (in Rus)

4.

Severskyi

I.V., Blagoveshenskyi V.P. Lavinoopasnye raiony Kazakhstana (Avalanche areas of Kazakhstan). Alma- Ata: Nauka, 1990. Page 172 (in Rus)

5.

Atlas

of natural and technogenic dangers and risks emergency to the situation in

Republic of Kazakhstan). Almaty: Kazgeodezia, 2010. Page 264. (in Rus)

6.

Zalichanov

M.Ch. Snezhnye laviny i perspectivy osvoenia gor Severnoi Osetii (Snow

avalanches and prospects of mastering of mountains of North Ossetia).

Ordzhonikidze: Ir, 1974. – Page 141. (in Rus)

7.

Isakov

A.L. , Monitoring of traffic avalanche areas using unmanned aerial vehicles) //

Vestnik TGASU. – 2014, -5, Page 143 (in Rus)

8.

Solov’ev

A.S., Mathematical design of the emergencies related to the origin and tails of

snow avalanches). Voronezh, 2014 (in Rus)

9.

Prokop A., Schoen P., Singer F., et

al. 2013. Determination avalanche modeling input parameters using terrestrial

laser scanning technology. - Proceedings of the International Snow Science

Workshop, 7-11 October 2013, Grenoble, France. P. 2-59.

10. Prokop, A., Schirmer, M., Rub, M., Lehning, M., and Stocker, M., 2008. A

comparison of measurement methods: Terrestrial laser scanning, tachymetry and

snow probing for the determination of spatial snow depth distribution on

slopes, Ann. Glaciol.,

49, pp. 210-216.

11. Prokop, A. and Panholzer, H., 2009. Assessing the capability of

terrestrial laser scanning for monitoring slow moving landslides, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst.

Sci., 9, pp. 1921–1928.

12. Seredovich V.A., Komissarov A.V.,

Komissarov D.V., Shirokova T.A. Terrestrial laser scanning. – Novosibirsck.:

SGGA, 2009 (in Rus)

13. Severskyi I.V., Blagoveshenskyi V.P.

Osenka lavinnoi opasnosti gornoi territorii (Estimation of avalanche hazard of

mountain territory). Alma- Ata, - 1983,- Page 120 (in Rus)

14. Turchaninova A.S. , Determination of zones of origin and

estimation of dynamic descriptions of snow avalanches., Moscow, 2013 (in Rus)

15. V.A. Seredovich, V.N.Oparin, V.F.Ushkin, A.V.Ivanov ,Forming

the bulk of digital surface models pit wall by laser scanning. Physical and

technical problems of mining. Mining informatics, Novosibirsk: SO RAN,

2007. – ¹ 5. – Page. 102–112. (in Rus)