ÓÄÊ 37’072

O. V. Volchanskyy, assosiate

professor, PhD in Physics

Kirovohrad

State Volodymyr Vynnychenko Pedagogical University,

Kirovohrad,

Ukraine

UNITED STATES CORPORATE RESEARCH:

History of University-Industry Linkages

The paper examines the process of emergence and

development of the university corporate research in the United States of

America.

Keywords : corporate research, employee training, university-industry

corporate linkages.

Among the factors

contributing to the success of the U.S. economy over the past decade – as

reflected in the doubling of productivity growth compared to the preceding two

decades – is the continued transformation of the U.S. economy toward a more

entrepreneurial form of capitalism. University research developed in corporate

linkages with industries through the Federal, State and philanthropic support

sets quite an important place in this process and as numerous studies show is

gathering momentum.

University-Industry Corporate Research is the interdependent research relationships

between universities and companies, under which universities, sponsored by

businesses, develop a technology or any other innovation which becomes the

company property. The goal of

the article is to survey the origin of the university-industry linkages in the

USA and the transformation of the former into corporate research interaction.

In the United States, university-industry research

relationships began with the industrial revolution [9]. Traditionally, it

was the industry that sought partnerships with universities as a means to

identify and train future employees. But very often big business and industry

created training and development departments or corporate universities of their

own to provide employees, both rookie and veteran, with the skills necessary to

perform their duties with precision and efficiency [8].

Table 1

Growth of Corporate

Universities [6]

.

.

Alongside, the relationships of industries and existing classical

universities developed. Before the mid-20-th century those relations were

random, narrow and not systemic. But closer to the present, as industrialization

increased, more universities became directly involved in the development of

technology for commercial purposes.

Universities and corporations first entered into agreements allowing

corporations to exploit intellectual property rights arising from university

research in the 1920s, when scientists from the University of Wisconsin founded

the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). This foundation sought to

protect university inventions through patent protection and to introduce

discoveries to the public through the use of licensing arrangements with

industry. Though WARF achieved early successes, the practice of patenting and

licensing inventions to industry did not reach widespread use until the 1940s,

when several other major

universities began following the technology licensing methods developed by WARF

[5].

Universities were a valuable source of scientific knowledge and

expertise for the nascent chemical and pharmaceutical industries from the late

19th century onward [7]. Those, in turn, stimulated research in universities. Biomedical and

biological research began to flourish at the University of Pennsylvania, the

University of Delaware, and Rutgers, thus inducing the simultaneous growth and

collocation of corporate research labs of companies such as Sterling, Merck,

DuPont, and Eli Lilly.

World War II was a boon for technology development. The programs

launched during the war and the scale of the funding provided by the

government, made large-scale scientific research an integrated part of the

activities of several leading American universities. Under this approach,

Harvard entered into a long-term, large-investment contract to develop a

particular technology. This type of university-corporate agreement provided an

additional model for commercializing university

inventions by concentrating on a particular objective for a collaborative

arrangement [5]. Later, when the

Cold War escalated, research for the purpose of technology development became

more firmly entrenched.

Massive Federal support for research became institutionalized in the

United States, along with equally massive spending on research and development

(R&D) by the corporate sector. A portion of this money was funneled to the

universities and helped formalize and cement university-industry links that had

begun multiplying in the 1940s.

The end of the 20-th century and the beginning of the

21-st century have been enduring a thunderstorm of changes so fundamental that some say the very idea of

the university is being challenged. Universities are experimenting with new

ways of funding, forging partnerships with private companies and engaging in

mergers and acquisitions.

Development

of University-Industry Corporate Relations becomes an objective, and therefore,

inevitable process for a number of reasons:

1. Democratization of higher

education—“massification”: the proportion of adults with higher educational

qualifications almost doubled between 1975 and 2000, from 22% to 41%.

2. The

rise of the knowledge economy. The best companies are now devoting at least a

third of their investment to knowledge-intensive intangibles such as R&D, licensing and marketing.

3. Globalisation.

US universities are opening campuses all around the world; and higher education

is turning into an export industry.

Competition. The traditional universities are being forced to compete

for students and research grants, and private companies are trying to break

into a sector which they regard as “the new health” [10].

4. The

demand for innovation. Ceaseless innovation that permits companies to

continuously refresh their product lines is becoming a necessity for many [8].

5. The

mounting cost and complexity of technologies [2] encourage firms to adopt “open”

innovation systems that favor partnerships, alliances, consortia, and

coordination of research effort with universities [1].

6. Necessity

for company researchers to deepen scientific knowledge for further

technological advance; to rely more on university-based researchers in emerging

fields where interdisciplinary expertise is required, such as nanotechnology

and biotechnology.

7. The conduct of cutting-edge research now requires teamwork—sometimes

straddling several disciplines—and expensive equipment for conducting

experiments and measuring results [4].

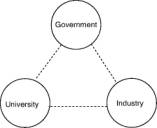

For those reasons now every industrial country is moving to make

university-industry links a centerpiece of its innovation systems, and the

notion of a triple helix –representing

the symbiotic relations yoking together the government, the universities, and

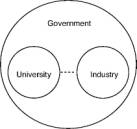

the business community – has acquired wide currency [3]. The path to the triple helix begins from two

opposing standpoints: a statist model of government controlling academia and

industry (Figure 1) and a laissez-faire model with industry, academia, and

government separate and apart from each other, interacting only modestly across

strong boundaries (Figure 2). New organizational innovations especially arise from interactions among the three helices (Figure 3).

The common triple helix format supersedes variation in national innovation

systems.

Table 2

Triple helix models

of university corporate relations

Fig. 1 Statistic model Fig. 2

Laissez-faire model Fig.3

Interactive model

Presently, Triple Helix intersection of relatively independent

institutional spheres generates hybrid organizations such as technology transfer offices in universities,

firms, and government research labs and business and financial support

institutions such as angel networks

and venture capital for new technology-based firms that are increasingly

developing around the world [3].

Thus, industry-university linkages originated as cooperation between

businesses and educational establishments, when the latter were training

companies’ future employees, and further transformed into current form of

interdependent research, when a new technology, profitable for a financing

company, is elaborated by university researchers.

REFERENCES

1. Chesbrough,

Henry William. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting

from Technology.– Boston : Harvard Business Review Press, 2003. – 226

p.

2. David,

Paul A., Dominique Foray, W. Edward

Steinmueller. The Research Network and the Economics of Science: From Metaphors

to Organizational Behaviours // In The Organization of Economic Innovation in

Europe / Ed. Gambardella A., Malerba F. –

Cambridge : Cambridge University

Press, 1999. – P. 303–342.

3. Etzkowitz,

Henry. The Triple Helix: University–Industry–Government. Innovation in Action.

– NY, London : Taylor & Francis

Group, 2008. – 164 p.

4.

Galison, Peter L. , Hevly B. Big Science: The Growth of Large-Scale Research. –

Stanford : Stanford University Press, 1994. – 408 p.

5. Hill D. Corporate Sponsored Research and

Development at Universities in the United States / David W. Hill // AIPPI

Journal. – 2002. – June // http://www.finnegan. com/resources/articles/articlesdetail.aspx?news=4447f1c1-c2fe-422a-9863-cd36a97158f9.

6. History

of Corporate Universities [article] // http://www.cuenterprise.com/ 777about/

cuhistory.php.

7. Mowery

D., Rosenberg N. 1998. Paths of

Innovation: Technological Change in 20th-century. – Cambridge : Cambridge

University Press. – 214 p.

8. Shahid,

Yusuf. University-Industry Links: Policy Dimensions. How Universities Promote

Economic Growth / Edit. Yusuf Sh., Nabeshlma K. – Washington : The World

Bank, 2007.– P.1–21.

9. University-Industry Linkages and UK Science

and Innovation Policy / Hughes, Alan [paper] // http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:ayfm

9Lv4Kv0J:citeseerx. ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download.

10. Wooldridge, Adrian. The brains

business. The Economist [article] // http://www.economist.com /node/4339960.