ENERGY PRINCIPLES OF

STABLE BIO-STRUCTURE FORMATION

G.À. Korablev*, V.I. Kodolov**, G.E. Zaikov***

*Izhevsk State Agricultural Academy

**Basic Research-Educational Center of Chemical Physics and Mesoscopy,

UdSC, UrD, RAS

**Institute of Biochemical Physics, RAS

ABSTRACT

The notion of spatial-energy

parameter (P-parameter), which is a complex characteristic of important atomic

values, is used to evaluate energy criteria of stable bio-structure formation.

The rationality of applying such methodology when investigating the formation

process of some nanosystems, conformation of polypeptide chains and fragments

of DNA molecules is demonstrated. The principles of biosystem formation and

stabilization have definite analogy with the conditions of wave processes. The

results obtained do not contradict the experimental data.

Keywords: spatial-energy parameter, nanosystems, conformation, biosystems, DNA

molecules.

Introduction

To

obtain the dependence between energy parameters of free atoms and dynamics of

structural formations in simple and complex systems is one of strategic tasks

in physical chemistry. Classical

physics and quantum mechanics widely use Coulomb interactions and their

varieties for this.

Thus

in [6] Van der Waals, orientation and charge-dipole interactions are referred

to electron-conformation interactions in biosystems. And as a particular case –

exchange-resonance transfer of energy. But biological and many cluster systems

are electroneutral in structural basis. And non-Coulomb equilibrium-exchange

spatial-energy interactions, i.e. non-charge electrostatic processes, are

mainly important for them.

The structural interactions of summed electron

densities of valence orbitals of corresponding conformation centers take place

– processes of equilibrium flow of electron densities due to overlapping of

their wave functions.

Heisenberg and Dirac

[10] proposed the exchange Hamiltonian derived in the assumption on direct

overlapping of wave functions of interacting centers. In this model

electrostatic interactions are modeled by effective exchange Hamiltonian acting

in the space of spin functions.

In

particular, such approach is applied to the analysis of structural interactions

in cluster systems [7]. It is demonstrated in Anderson’s works [9] that in

compounds of transition elements when the distance between paramagnetic ions

considerably exceeds the total of their covalent radii, “superexchange”

processes of overlapping cation orbitals take place through the anion between

them.

In

this work similar equilibrium-exchange processes are evaluated through the

notion of spatial-energy parameter – Ð-parameter.

1.

Initial criteria

In the systems in

which the interaction proceeds along the potential gradient (positive work),

the resultant potential energy is found based on the principle of adding

reciprocals of corresponding energies of subsystems [2].

Thus

the energy of atom valence orbitals (responsible for interatomic interactions)

can be calculated by the principle of adding reciprocals of some initial energy

components based on the following equations:

![]() or

or ![]() ;

; ![]() (1),(2),(3)

(1),(2),(3)

Here: Wi – electron orbital energy [14]; ri – orbital radius of i–orbital [13];

q=Z*/n* [11,12], ni –

number of electrons of the given orbital, Z*

and n* – nucleus effective charge

and effective main quantum number, r – bond dimensional characteristics.

Ð0 is called a spatial-energy parameter (SEP), and ÐE – effective Жparameter (effective SEP). Effective SEP has a physical sense of some

averaged energy of valence electrons in the atom and is measured in energy

units, e.g. electron-volts (eV).

Calculation results by the equations (1,2,3) are given in Table 1.

Table 1

Ð-parameters of atoms calculated via the electron bond

energy

|

Atom |

Valence

electrons |

W (eV) |

ri (Å) |

q2 0 (eVÅ) |

Ð0 (eVÅ) |

R (Å) |

Ð0/R (eV) |

|

H |

1S1 |

13.595 |

0.5292 |

14.394 |

4.7969 |

0.5292 0.375 0.28 |

9.0644 12.792 17.132 |

|

Ñ |

2P1 2P2 2P3ã 2S1 2S2 2S1+2P3ã 2S1+2P1ã 2S2+2P2 |

11.792 11.792 19.201 |

0.596 0.596 0.620 |

35.395 35.395 37.240 |

5.8680 10.061 13.213 9.0209 14.524 22.234 13.425 24.585 24.585 |

0.77 0.67 0.60 0.77 0.67 0.60 0.77 0.77 0.77 0.77 0.77 0.77 0.67 0.60 |

7.6208 8.7582 9.780 13.066 15.016 16.769 17.160 11.715 18.862 28.875 17.435 31.929 36.694 40.975 |

|

N |

2P1 2P2 2P3 2S2 2S2+2P3 |

15.445 25.724 |

0.4875 0.521 |

52.912 53.283 |

6.5916 11.723 15.830 17.833 33.663 |

0.70 0.55 0.70 0.63 0.70 0.55 0.70 0.70 |

9.4166 11.985 16.747 18.608 22.614 28.782 25.476 48.090 |

|

O |

2P1 2P1 2P2 2P4 2S2 2S2+2P4 |

17.195 17.195 17.195 33.859 |

0.4135 0.4135 0.4135 0.450 |

71.383 71.383 71.383 72.620 |

6.4663 11.858 20.338 21.466 41.804 |

0.66 0.55 0.66 0.59 0.66 0.59 0.66 0.66 0.59 |

9.7979 11.757 17.967 20.048 30.815 34.471 32.524 63.339 70.854 |

In

the systems in which the interactions proceed against the potential gradient

(negative performance) the algebraic addition of their masses as well as the

corresponding energies of subsystems is performed [2]. Thus, for the

interaction of similarly charged (homogeneous) subsystems the principle of

algebraic addition of their P-parameters is performed:

![]() (4)

(4) ![]() (5)

(5)

where

R – dimensional characteristic of atom (or chemical bond).

Modifying the rules of adding the reciprocals of the

energy magnitudes of sub-systems as applicable to complex structures, we can

obtain the equations to calculate a ÐÑ-parameter

of a complex structure:

(6)

(6)

where N1 and N2

– number of homogeneous atoms in sub-systems.

The calculation results in

this equation for some atoms and radicals of biosystems are given in Table 2.

The

value of the relative difference of P-parameters of interacting

atoms-components – the structural interaction coefficient α is used as the

main numerical characteristic of structural interactions in condensed media:

![]() (7)

(7)

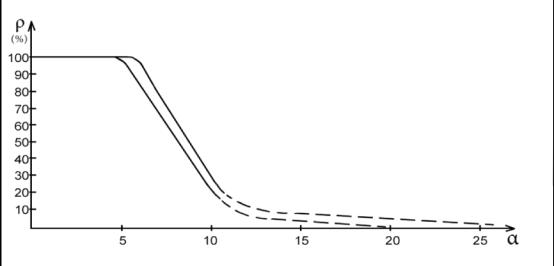

Applying the reliable experimental data we obtain the nomogram of

structural interaction degree dependence (ρ) on coefficient α, the

same for a wide range of structures (Fig.1). This approach gives the

possibility to evaluate the degree and direction of the structural interactions

of phase formation, isomorphism and solubility processes in multiple systems,

including molecular ones.

Applying the reliable experimental data we obtain the nomogram of

structural interaction degree dependence (ρ) on coefficient α, the

same for a wide range of structures (Fig.1). This approach gives the

possibility to evaluate the degree and direction of the structural interactions

of phase formation, isomorphism and solubility processes in multiple systems,

including molecular ones.

Fig. 1

Nomogram of structural interaction degree dependence (ρ) on

coefficient α

Table

2

Structural

ÐÑ-parameters calculated via electron bond energy

|

Radicals, molecule fragments |

|

|

|

Orbitals |

|

ÎÍ |

9.7979 30.815 17.967 |

9.0644 17.132 17.132 |

4.7084 11.011 8.7710 |

O

(2P1) O

(2P4) O

(2P2) |

|

Í2Î |

2·9.0644 2·17.132 |

17.967 17.967 |

9.0237 11.786 |

O

(2P2) O

(2P2) |

|

ÑÍ2 |

17.160 31.929 36.694 |

2·9.0644 2·17.132 2·9.0644 |

8.8156 16.528 12.134 |

Ñ (2S12P3ã) Ñ (2S22P2) Ñ (2S12P3ã) |

|

ÑÍ3 |

31.929 15.016 |

3·17.132 3·9.0644 |

19.694 9.6740 |

Ñ (2S22P2) Ñ (2P2) |

|

ÑÍ |

36.694 17.435 |

17.132 17.132 |

11.679 8.6423 |

Ñ (2S22P2) Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

NH |

16.747 19.538 48.090 |

17.132 17.132 17.132 |

8.4687 9.1281 12.632 |

N(2P2) N(2P2) N(2S22P3) |

|

NH2 |

19.538 16.747 28.782 |

2·9.0644 2·17.132 2·17.132 |

9.4036 12.631 18.450 |

N(2P2) N(2P2) N(2P3) |

|

Ñ2Í5 |

2·31.929 |

5·17.132 |

36.585 |

Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

NO |

19.538 28.782 |

17.967 20.048 |

9.3598 11.817 |

N(2P2) N(2P3) |

|

ÑÍ2 |

31.929 |

2·9.0644 |

11.563 |

Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

ÑÍ3 |

16.769 |

3·17.132 |

12.640 |

Ñ (2P2) |

|

ÑÍ3 |

17.160 |

3·17.132 |

12.865 |

Ñ (2P3ã) |

|

ÑΖÎÍ |

8.4405 |

8.7710 |

4.3013 |

Ñ (2P2) |

|

ÑÎ |

31.929 |

20.048 |

12.315 |

Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

Ñ=Î |

15.016 |

20.048 |

8.4405 |

Ñ (2P2) |

|

Ñ=Î |

31.929 |

34.471 |

16.576 |

Î (2P4) |

|

ÑÎ=Î |

36.694 |

34.471 |

17.775 |

Î (2P4) |

|

Ñ–ÑÍ3 |

31.929 |

19.694 |

12.181 |

Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

Ñ–ÑÍ3 |

17.435 |

19.694 |

9.2479 |

Ñ (2S12P1) |

|

Ñ–NH2 |

31.929 |

18.450 |

11.693 |

Ñ (2S22P2) |

|

Ñ–NH2 |

17.435 |

18.450 |

8.8844 |

Ñ (2S12P1) |

|

Ñ–ÎÍ |

8.7572 |

8.7710 |

4.3821 |

|

2. Formation of carbon

nanostructures

After different

allotropic modifications of carbon nanostructures (fullerenes, tubules) have

been discovered, a lot of papers dedicated to the investigations of such

materials, for instance were published, determined by the perspectives of their

vast application in different fields of material science.

The main

conditions of stability of these structures formulated based on modeling the

compositions of over thirty carbon clusters are given [8]:

1) Stable carbon

clusters look like polyhedrons where each carbon atom is three-coordinated.

2) More stable

carbopolyhedrons containing only 5- and 6-term cycles.

3) 5-term cycles

in polyhedrons – isolated.

Let us

demonstrate some possible explanations of such experimental data based on the

application of spatial-energy concepts. The approximate equality of effective

energies of interacting subsystems is the main condition for the formation of

stable structure in this model [4] based on the following equation:

;

; ![]() (8)

(8)

where Ê – coordination number, R – bond dimensional characteristic.

At the same time,

the phase-formation stability criterion (coefficient α) is the relative difference of parameters Ð1 and Ð2 that is calculated following the equation (1) and is αST<(20-25)% (according to the nomogram).

During the interactions of similar

orbitals of homogeneous atoms ![]() we have

we have

![]() (8à)

(8à)

Let us consider

these initial notions as applicable to certain allotropic carbon modifications:

1. Diamond.

Modification of structure where Ê1=4, Ê2=4; ![]() , R1=R2, Ð1=Ð2 and α=0. This is absolute

bond stability.

, R1=R2, Ð1=Ð2 and α=0. This is absolute

bond stability.

2. Non-diamond

carbon modification for which ![]() , Ê1=1; R1=0,77Å; Ê2=4;

, Ê1=1; R1=0,77Å; Ê2=4; ![]() , α=3,82%.

Absolute stability due to ionic-covalent bond.

, α=3,82%.

Absolute stability due to ionic-covalent bond.

3. Graphite. ![]() , Ê1=Ê2=3, R1=R2, α=0 – absolute

bond stability.

, Ê1=Ê2=3, R1=R2, α=0 – absolute

bond stability.

4. Chains of

hydrocarbon atoms consisting of the series of homogeneous fragments with

similar values of P-parameters.

5. Cyclic organic

compounds as a basic variant of carbon nanostructures. Apparently, not only

inner-atom hybridization of valence orbitals of carbon atom takes place in

cyclic structures, but also total hybridization of all cycle atoms.

But not only the

distance between the nearest similar atoms by bond length (d) is the basic

dimensional characteristic, but also the distance to geometric center of cycle

interacting atoms (D) as the geometric center of total electron density of all

hybridized cycle atoms.

Then the basic

stabilization equation for each cycle atom will take into account the average

energy of hybridized cycle atoms:

;

; ![]() (9) (9à)

(9) (9à)

where ΣÐ0=Ð0N; N – number of homogeneous atoms, Ð0 – parameter of one cycle atom, Ê – coordination number relatively to geometric center of cycle atoms.

Since in these cases Ê![]() =K

=K![]() and N

and N![]() =N

=N![]() , Ê=N, the following simple correlation for paired bond appears:

, Ê=N, the following simple correlation for paired bond appears:

;

; ![]() (10)

(10)

During the

interactions of similar orbitals of homogeneous atoms ![]() , and then:

, and then:

![]() (11)

(11)

Equation (10)

reflects a simple regularity of stabilization of cyclic structures:

The

main condition of formation and stability of structures is an approximate

equality of effective interaction energies of atoms along all directions of

interatomic bond.

The corresponding

geometric comparison of cyclic structures consisting of 3, 4, 5 and 6 atoms

results in the conclusion that only in 6-term cycle (hexagon) the bond length

(d) equals the length to geometric center of atoms (D): d=D.

Such calculation

of α following the equation (7), gives for hexagon α=0 and absolute

bond stability. And for pentagon d≈1.17D and the value of α=16%,

i.e. this is the relative stability of the structure being formed. For the

other cases α>25%, therefore many biosystems such as, for example,

nucleic acids, contain only 5- and 6-term cyclic fragments.

The calculations

and comparisons performed based on spatial-energy concepts allow explaining

some formation peculiarities of hexagonal structures in biosystems.

3. Formation of polypeptide chain

Main

components of organic compounds constituting 98 % of cell element composition:

carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen. The polypeptide bond formed by COOH and

NH2 groups of amino acid CONH is the binding base of protein

biopolymers of a cell. At the same time, carbon atoms are more frequently found

in polypeptide chain nodes, and sometimes – nitrogen atoms.

Fragments of polypeptide chain

nodes are formed of CH, OH, CO, NH, NH2, CO-OH atom groups and some

radicals. In accordance with conformation energy criteria of such chain, the

approximate equality of their ÐE-parameters needs

to be followed, both separately for all fragments and chain atomic nodes. The

calculations of possible variants are given in Table 2. Its analysis results in

the conclusion of the existence possibility of three series of such relations.

Their summarized data are given in Table 3. Such cyclicity of functional

correlations can be evaluated from the point of quantum-wave properties of

P-parameter [5].

The

interference minimum, oscillation weakening

(in anti-phase) takes place if the difference in wave move (∆) equals the

odd number of semi-waves:

∆ = (2n +1)![]() = l(n

+

= l(n

+ ![]() ), where n = 0, 1, 2,

3, … (12)

), where n = 0, 1, 2,

3, … (12)

It means that the minimum of interactions take place

if P-parameters of interacting structures are also “in anti-phase” – either

oppositely charged systems or heterogeneous atoms are interacting (e.g. during

the formation of valence-active radicals CH, CH2, CH3, NO2

…, etc.).

In

this case, P-parameters are summed up based on the principle of adding the

reciprocals of P-parameters – equations (1-3).

The difference in wave move (∆) for Ð-parameters can be evaluated

via their relative value (g=![]() ) or via

relative difference of Ð-parameters (coefficient a), which give an odd number at minimum of

interactions:

) or via

relative difference of Ð-parameters (coefficient a), which give an odd number at minimum of

interactions:

g=![]() … At n=0

(basic state)

… At n=0

(basic state) ![]() (12à)

(12à)

Interference maximum,

oscillation enhancing (in phase) takes place if the difference in wave move equals

an even number of semi-waves:

∆=2n![]() =ln

or ∆=l(n+1) (13)

=ln

or ∆=l(n+1) (13)

As applicable to P-parameters, the maximum enhance of

interaction in the phase corresponds to the interactions of similarly charged

systems or systems homogeneous by their properties and functions (e.g. between

the fragments or blocks of complex organic structures, such as CH2

and NNO2).

Then: g=![]() =(n+1) (13à)

=(n+1) (13à)

By this model, the maximum of

interactions corresponds to the principle of algebraic addition of P-parameters

– equations (4,5). When n=0 (basic state), we have Ð2=Ð1, or: the maximum

of structure interaction occurs if their P-parameters are equal. This postulate

and equation (13à) are used as basic conditions

for the formation of stable structures [4].