Study of the gas migration in

Paris basin

Aidana MURATBEKOVA[1], Raymond

MICHELS[2],

Irina PANFILOVA[3],

Talgat Ensepbayev[4]

[1] Kazakh National

Technical University named K.I.Satpaev, Almaty, KAZAKHSTAN aidanochka@mail.ru

[1] Laboratory

“GeoRessoureces”, Nancy, FRANCE

[1] Laboratory “LEMTA”,

Nancy, FRANCE

[1] Kazakh National

Technical University named K.I.Satpaev, Almaty, KAZAKHSTAN

Abstract

The

main objective of this study was to understand the gases migration in the Paris

basin. The analysis of different hypothesis was made on the data from ANDRA’s

drillings EST433 in the Meuse – Haute Marne area. These data are sedimentary

logs, gases concentration profiles and petrophysical data. Thanks to a

geological study of the sector, it was expected to explain the origin and the

migration of the gases. As it was studied before by Prinzhofer et al.

(2009), the migration of gases,

dissolved in porewater can be explained

by processes, as diffusion, adsorption, and by flux of aquifer in some of

layers. So to verify the consistency of the hypothesis and to better understand

the gas migration in this region, there was made the simulation with Comsol

software.

Methane

concentration measurements made at various depths along a 2000 m depth borehole

drilled in the eastern part of the Paris basin and reaching the Triassic

conglomerates were used to establish a vertical profile of dissolved methane

concentration and hydrocarbon gases molar composition. Wireline logging tools

were used to measure porosity in the various formations. Shallower levels show

the highest methane concentration, and going upwards, values are getting lower,

yet molar compositions show a complex pattern. The data set obtained by

wireline logging measurements was used as inputs for numerical simulations of

1D methane diffusion throughout the 2000 m profile. Several assumptions

regarding the transport properties in the various sedimentary layers were

tested and all were found to yield fairly good agreement between modeled and

measured methane relative molar concentrations in the dissolved hydrocarbon

gases. Moreover, the modeling results suggest that the Keuper massive halite

level associated with the upper Muschelkalk pre-evaporitic series efficiently

isolates the overlying layers from any input from deeper formations in the

Meuse/Haute Marne area. Last, diffusive parameters were plotted according to

Archie’s law, which therefore allows an estimation of ![]() (non-reactive

species) from the knowledge of both the sample total porosity and the

corresponding exponent m = 2. Rock hydrocarbon source potential, clay

lithologies and relationships to aquifers are major parameters which govern gas

diffusion. The overall complex pattern can however be reproduced by the model

and set a physical framework to future combined geological and geochemical

interpretation.

(non-reactive

species) from the knowledge of both the sample total porosity and the

corresponding exponent m = 2. Rock hydrocarbon source potential, clay

lithologies and relationships to aquifers are major parameters which govern gas

diffusion. The overall complex pattern can however be reproduced by the model

and set a physical framework to future combined geological and geochemical

interpretation.

Keywords:

methane, diffusion, convection, aquifers, Paris basin, Comsol, modelling

Introduction

Introduction to the study area

Location of the well EST433 and stratigraphy

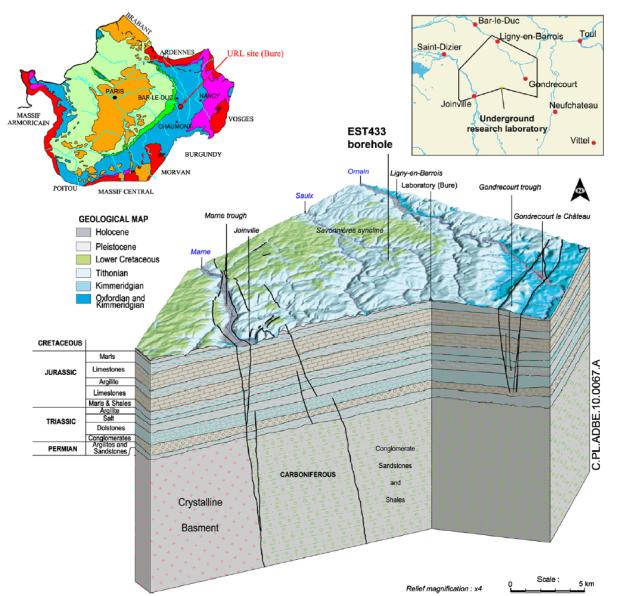

The Paris Basin is located in

the northern part of France (Figure 1) and contains sedimentary formations aged from

Triassic to Tertiary (Guillocheau et al., 2000). The study area is in the

eastern part of the Paris basin Îøèáêà! Èñòî÷íèê ññûëêè íå íàéäåí.which

is characterized by a basement made of the Carboniferous coal basin. A well was

bored near the URL (EST433 well) to reach the base of the Triassic in order to

estimate the geothermal potential (Landrein et al., 2013). The sedimentary

layer is consisted of sandstone, limestone, marl and clay layers with one main

salt-rich level in the Keuper formation, from 1616 to 1416 m in depth.

Paleo-temperature reconstructions indicate that temperature is between 10-70°C

in basin (Blaise et al., 2014). The main mass transfer process is reported as diffusion (Rebeix et al., 2014). Also from the studies of Landrein et al.(2013) the Paris basin has a geothermal potential.

251658240

Figure 1 – Geological context of the studied area – Left: the Paris basin (Linard

et al., 2011); Right: the Meuse/Haute-Marne Site. (Battani et al., 2011).

Hydrogeological

background of the aquifers in basin

The sedimentary cover also

includes formations which are known to be aquifers: Tithonian limestones,

Oxfordian limestones, Dogger oolitic limestones, Rhetian bioclastic limestone,

and Buntsandstein sandstones.

The Tithonian aquifer,

situated between ![]() m and the

surface. The second aquifer formation, the Oxfordian limestones, lies between

m and the

surface. The second aquifer formation, the Oxfordian limestones, lies between ![]() m and

m and ![]() m. Average

water content of the Oxfordian layer ranges between 2 and 3%. Seven main levels

of relatively high porosity were identified and were assumed to indicate zones

of relatively high water productivity. Below the COx formation, the Dogger

oolitic limestone aquifer is located between depths of

m. Average

water content of the Oxfordian layer ranges between 2 and 3%. Seven main levels

of relatively high porosity were identified and were assumed to indicate zones

of relatively high water productivity. Below the COx formation, the Dogger

oolitic limestone aquifer is located between depths of ![]() m to

m to ![]() m. The top

10 m of this formation, named the “dalle nacrée” level, correspond to

highly recrystallized carbonates with very limited porosity and permeability.

Over the study area, two water production levels are evidenced (at -710m and

-766m, with a contribution 60 times lower in term of flux for the second one).

The Rhetian bioclastic limestone layer, between

m. The top

10 m of this formation, named the “dalle nacrée” level, correspond to

highly recrystallized carbonates with very limited porosity and permeability.

Over the study area, two water production levels are evidenced (at -710m and

-766m, with a contribution 60 times lower in term of flux for the second one).

The Rhetian bioclastic limestone layer, between ![]() m and

m and ![]() m, is known

to have only limited aquifer characteristics at a regional scale, mainly to the

east of the study area. There, no water circulation has been detected during

drilling of the EST433 borehole. The Buntsandstein sandstones constitute the

deepest aquifer lying between

m, is known

to have only limited aquifer characteristics at a regional scale, mainly to the

east of the study area. There, no water circulation has been detected during

drilling of the EST433 borehole. The Buntsandstein sandstones constitute the

deepest aquifer lying between ![]() and

and ![]() m. Although,

one water production level was encountered in Buntsandstein at

m. Although,

one water production level was encountered in Buntsandstein at ![]() m on the EST433 borehole (Rebeix et al., 2014).

m on the EST433 borehole (Rebeix et al., 2014).

The Dogger aquifer consists of oolithic and reef

limestone (Îøèáêà! Èñòî÷íèê ññûëêè íå íàéäåí.)

of low porosity (6–9% average) and low permeability (from ![]() to

to ![]() m/s) (Buschaert et al., 2006). The Oxfordian limestone

aquifer exhibits variable porosity (3 to 25%) and permeability similar to the

Dogger aquifer (from

m/s) (Buschaert et al., 2006). The Oxfordian limestone

aquifer exhibits variable porosity (3 to 25%) and permeability similar to the

Dogger aquifer (from ![]() to

to ![]() m/s) (Delay et al., 2006). Hydrogeological models for the two

aquifers indicate westward flow.

m/s) (Delay et al., 2006). Hydrogeological models for the two

aquifers indicate westward flow.

Stratigraphy of the studied

area with depth indications for platform C can be observed from the article by

Linard et al., 2011.

There are compounds of

hydrocarbon gas (methane, ethane, propane, iso- and normal-butane) presented as

dissolved compounds in the porewater in eastern Paris Basin, France. Results

indicate that the studied hydrocarbons contain significant amounts of ethane,

butane and propane, in addition to methane. Methane concentration in the pore

water profile displays not linear increase in methane concentrations in log

scale with depth. The maximum concentration is in the lower Triassic, the lower

part of the well E433 and further to upper layers, lower becomes methane

concentration values.

In regards to organic geochemistry data (Fleck et al.,

2001; Blaise et al., 2014) two major sources of hydrocarbon gases can be

considered: the carboniferous basement (higher plants coal layers) and the

Liassic marine source rocks. By considering the physical parameters of the rock

layers (lithology, porosity, thickness) contrasted properties were identified

(very low porosity of evaporate layers, low porosity of clay layers, higer permeability

of sandstones or carbonates layers acting as aquifers).

The

groundwater flow is mostly occurs through fractures or connected pores. That is

why the gas migration in liquid-saturated porous medium, as in Paris basin, can

be explained by advective flow combined with diffusion (Rebeix et al., 2014;

Battani et al., 2011). Convection–diffusion equation was used to determine the

mass transport in this medium. As diffusional flow in pores may be described by

an effective diffusion coefficient, the differential equation for mass

transport in a porous material in this numerical simulation can be written as:

|

|

Where,

![]() is a characteristic

concentration of methane in gas mixture, [dimensionless] ;

is a characteristic

concentration of methane in gas mixture, [dimensionless] ;

![]() is the effective

diffusion coefficient in porous medium,

is the effective

diffusion coefficient in porous medium, ![]() ;

; ![]() is Darcy velocity,

is Darcy velocity, ![]() .

.

In

Îøèáêà! Èñòî÷íèê ññûëêè íå íàéäåí.

the concentration is shown in percentage of mole fraction. In the numerical

model we use the specific concentration ![]() , which is equal to the ratio between the masse fraction and

its maximum value.

, which is equal to the ratio between the masse fraction and

its maximum value.

The

effective diffusion coefficient for transport through the pores is estimated as

follows:

|

|

2 |

![]() is the diffusion

coefficient of the species in the fluid (e.g., water) without the presence of

the sediment matrix.

is the diffusion

coefficient of the species in the fluid (e.g., water) without the presence of

the sediment matrix.

The

porosity (![]() ) of porous media can be determined (pore size distribution

and tortuosity are unknown). Therefore the effective diffusivity is often

defined as a function of

) of porous media can be determined (pore size distribution

and tortuosity are unknown). Therefore the effective diffusivity is often

defined as a function of ![]() alone (

alone (![]() ). So the effective diffusion can be introduced by following equation:

). So the effective diffusion can be introduced by following equation:

|

|

3 |

Where,

|

|

4 |

This

is called formation factor. Here, ![]() is a fitting

parameter and

is a fitting

parameter and ![]() is a cementation factor.

is a cementation factor.

In

numerical modelling it was taken as ![]() , because in studying this area before by Descostes et al. in

2008 it was mentioned that

, because in studying this area before by Descostes et al. in

2008 it was mentioned that ![]() . This value was discussed before in work of Battani et al.

(2011).

. This value was discussed before in work of Battani et al.

(2011).

In

materials of low porosities as in this study, ![]() , the cementation factor can be more than 2,

, the cementation factor can be more than 2, ![]() (Grathwohl P., 1998).

(Grathwohl P., 1998).

It

was assumed that the molecules of the solute (in our case methane) are

spherical, so the diffusion coefficient of the species in the fluid (e.g.,

water with dissolved gas mixture) without the presence of the sediment matrix

is calculated by Stokes-Einstein eq.:

|

|

5 |

Where,

![]() is a dynamic

viscosity of liquid,

is a dynamic

viscosity of liquid, ![]() or

or ![]() ;

; ![]() is Boltzman constant,

which is equal to:

is Boltzman constant,

which is equal to:

![]()

![]() is a temperature of the medium,

is a temperature of the medium, ![]() ; π is an Euler constant, which is equal to 3.14;

; π is an Euler constant, which is equal to 3.14; ![]() is a molecular radius

of solute,

is a molecular radius

of solute, ![]() ; in our case

; in our case ![]() was taken as a diffusing solute.

was taken as a diffusing solute.

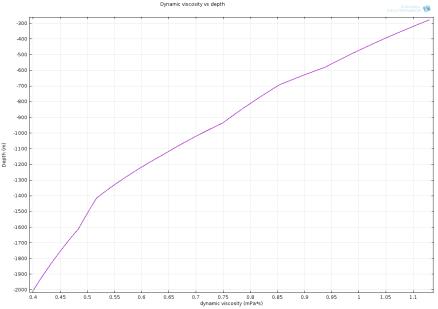

The

dynamic viscosity is an important fluid property when analyzing liquid behavior

and fluid motion near solid boundaries or even diffusion process. So, to be

more precise, viscosity was calculated as a function of temperature in the

equation, which is presented below (Viswanath, 2007).

|

|

Where

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() are the empirical

constants, and the values depend on type of fluid. As in our case the medium is

saturated by water, they are in following values:

are the empirical

constants, and the values depend on type of fluid. As in our case the medium is

saturated by water, they are in following values:

![]()

![]()

![]()

From

petrophysical data the cross section was divided into 44 domains, in

relationship to their fluid transport properties (merely permeable vs

impermeable). Indeed, the stratigraphy is dominated by three major types of

lithology deposited during well-defined stratigraphic periods: sandstone in the

lower Triassic, claystone and evaporates during upper Triassic, mainly

claystone during lower Jurassic, carbonates during middle Jurassic, claystone

during upper Jurassic followed by carbonates. (Landrein et al., 2013 for details).

Porosity

Porosity

(![]() ) is a key factor for solute transport process in porewaters.

Wireline logging results indicate that most porosity values range between 0 and

0.25, with some meter-scale highly porous levels (

) is a key factor for solute transport process in porewaters.

Wireline logging results indicate that most porosity values range between 0 and

0.25, with some meter-scale highly porous levels (![]() ).

).

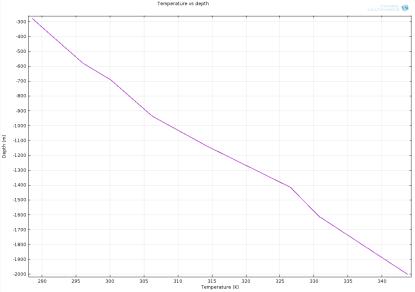

The

temperature influences to the plenty amount of parameters of the fluid

properties, such as in our case, dynamic viscosity. That is why it is important

to identify the temperature gradient values for each domain. It is introduced

in Table 1 The data of hydrological and thermometric measurements

are from article by Landrein P. et al., 2013.

Table 1 – Temperature gradient parameters observed from article by Landrein P. et

al., 2013

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

258 |

581 |

323 |

288,06 |

296,08 |

8,02 |

0,0248 |

|

581 |

691 |

110 |

296,08 |

300,1 |

4,02 |

0,0365 |

|

691 |

937 |

246 |

300,1 |

306,26 |

6,16 |

0,0250 |

|

937 |

1135 |

198 |

306,26 |

314,16 |

7,9 |

0,0399 |

|

1135 |

1415 |

280 |

314,16 |

326,54 |

12,38 |

0,0442 |

|

1415 |

1611 |

196 |

326,54 |

330,76 |

4,22 |

0,0215 |

|

1611 |

1862 |

251 |

330,76 |

339,15 |

8,39 |

0,0334 |

![]() is the thickness of

the domain between

is the thickness of

the domain between ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() is the difference

between

is the difference

between ![]() and

and![]() ,

, ![]()

![]() is the temperature

gradient in domain with thickness

is the temperature

gradient in domain with thickness ![]() ,

, ![]()

In Comsol temperature is given by

following equation:

|

|

7 |

Where, ![]() is the lowest

temperature for each domain,

is the lowest

temperature for each domain, ![]() ;

; ![]() is the depth at the

lowest temperature,

is the depth at the

lowest temperature, ![]() ;

; ![]() is the temperature

gradient for each domain,

is the temperature

gradient for each domain, ![]() . After entering, it was observed the dependence of depth and

temperature, figured in Îøèáêà! Èñòî÷íèê ññûëêè íå íàéäåí..

. After entering, it was observed the dependence of depth and

temperature, figured in Îøèáêà! Èñòî÷íèê ññûëêè íå íàéäåí..

251658240

Figure 2 – Thermal profile of EST433 as generated by

Comsol using the parameters selected from tables 3

The

value of dynamic viscosity was inserted for all domains by the equation 1 The result of entering equation for viscosity is

shown in Figure 3.

251658240

Figure 3 – Water

dynamic viscosity profile as a function of depth in the EST433 well in calculation using Comsol, the equation 1 and

parameters defined in tables 3

From this graphic, it is easy to determine that upper

we are, water becomes more viscous. And it causes to decreasing of the

diffusion coefficient ![]()

It

is necessary to introduce time limit for the equation. For the simulation 200

million years was chosen. Because the age of the first significant cap-rock

deposit: the upper Triassic is 200 million years, even 270 million years is the

oldest age of gas formation from the Carboniferous source-rocks. So as a time

limit, it was taken as 200 million years for diffusion process.

Conclusion

The

objective of this study was to understand the gases migration in the Paris

basin. In this article I tried to make some investigation af articles and data

from ANDRA’s EST433 drilling in the Meuse – Haute Marne area. It was clear that

the migration of gas is caused by additional sources, not only by diffusion of

hydrocarbon from the carboniferous basement So, to verify the

consistency of the hypothesis and to better understand the gas migration in

this region, there should be made the further detailed simulation with Comsol

software.

References

Battani A., Smith

T., Robinet J.C., Brulhet J., Lavielle B., Coelho D., 2011. Contribution of logging tools to understanding helium porewater data

across the Mesozoic sequence of the East of the Paris Basin. Geochimica et

Cosmochimica Acta 75, 7566–7584

Blaise T., Barbarand

J., Kars M., Ploquin F., Aubourg C., Brigaud B., Cathelineau M., El Albani A.,

Gautheron C, Izart A., Janots D.,

Michels R., Pagel M., Pozzi J.-P., Boiron M.C., Landrein P., 2014. Reconstruction of low temperature (<100 _C) burial in sedimentary

basins: A comparison of geothermometer in the intracontinental Paris Basin.

Marine and Petroleum Geology 53, 71-87.

Buschaert S., Giannesini

S., Benedetti L., Lavastre V., Gaucher E.C., Lacroix M., Lavielle B., Michelot

J.-L., France-Lanord C., Bourlès D., Finkel R., Lancelot J., Dewonck S.,

Vinsot A., 2006. Water geochemistry contribution to

the understanding of the regional hydrogeological system. Mém.

Soc. Géol. Fr. 178, 91–114.

Delay J., Trouiller

A., Lavanchy J.M., 2006. Propriétés hydrodynamiques du

Callovo-Oxfordien dans l'Est du bassin de Paris: comparaison des

résultats obtenus selon différentes approaches. C. R. Geosciences

338 (12–13), 892–907.

Fleck S., Michels

R., Izart A., Elie M., Landais P., 2001. Palaeoenvironmental

assessment of Westphalian fluvio-lacustrine deposits of Lorraine (France) using

a combination of organic geochemistry and sedimentology. International Journal

of Coal Geology 48, 65– 88.

Grathwohl P., 1998. Diffusion in natural porous media:

contaminant transport, sorption/desorption and dissolution kinetics. Springer

US 1, XVI, 207.

Guillocheau F.,

Robin C., Allemand P., Bourquin S., Brault N., Dromart G., Friedenberg R.,

Garcia J.P., Gaulier J.M., Gaumet F., Grosdoy B., Hanot F., Le Strat P.,

Mettraux M., Nalpas T., Prijac C., Rigollet C., Serrano O., Grandjean G., 2000.

Meso-cenozoic geodynamic evolution of the Paris Basin:

3D stratigraphic constraints. Geodyn. Acta13 (4), 189–246.

http://www.viscopedia.com/viscosity-tables/substances/water/

https://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20130623193455AA28HUi.

Kolesnichenko

E.A., Artemiev V.B., Kolesnichenko I.E.,

Lyubomischenko E.I., 2011. The natural laws of the methane in coal

seams. Book in russion, 75.

Landrein P.,

Vigneron G., Delay J., Lebon P, Pagel M., 2013. Lithologie, hydrodynamisme et

thermicité dans le système sédimentaire multicouche

recoupé par les forages Andra de Montiers-sur-Saulx (Meuse). Bull. Soc.

géol. France, t. 184, no 6, pp. 519-543.

Linard Y., Vinsot

A., Vincent B., Delay J., Wechner S., De La Vaissière R., Scholz E.,

Garry B., Lundy M., Cruchaudet M., Dewonck S., Vigneron G., 2011. Water flow in the Oxfordian and Dogger limestone around the

Meuse/Haute-Marne Underground Research Laboratory . Elsevier, Physics and

Chemistry of the Earth 36, pp.1450–1468.

Prinzhofer

A., Girard J., Buschaert S., Huiban Y., Noirez S., 2009. Chemical and isotopic

characterization of hydrocarbon gas traces in porewater of very low

permeability rocks: The example of the Callovo-Oxfordian argillites of the

eastern part of the Paris Basin. Elsevier Chemical Geology,

vol. 260, pp.269-277.

Rebeix R., Le Gal La

Salle C., Jean-Baptiste P., Lavastre V., Fourré E., Bensenouci F.,

Matray J.M., Landrein P., Shouakar-Stash O., Frape S.K., Michelot J.L.,

Lancelot J., 2014. Chlorine transport processes through

a 2000 m aquifer/aquitard system. Marine and Petroleum Geology 53,

102–116.