MODELLING FRACTURING IN SHALES WITH FLUID ROCK INTERACTIONS

Aibol

NUSSIPKOZHAYEV[1], Jean-Jacques Royer[2], Murat BAIMUHAMETOV1

[1] Kazakh National Technical University after

K.Satpayev

2

∗Universit´e

de Lorraine UdL, CNRS-GeoRessources (UMR7359), ENSG-INPL, gOcad-ASGA,

Vandoeuvre, France.

Abstract

With the last

advances in uranium mining such as In-situ leaching technology the

implementation of this technology into other ore mining fields nowadays is

possible.

More exactly

it comes to the application of above mentioned technology to the copper mine

sites. This work focuses on the

creation of the structural model on gOcad of

the testing area at the Rudna mine site and on the implementation of a

hydraulic fracturing process to increase the in-situ permeability. The

hydraulic fracturing was performed using a wizard developed in the gOcad

environment. In-situ recover methods –

an alternative way to produce metals, were explained. The rock elastic

properties were estimated from laboratory assays performed on rock samples,

especially Vp and Vs seismic, density and

porosity. These values were interpolated in the grid model and used to simulate

the fracturing. The report shows simulation results using the gOcad software.

Permeability increases with injection pressure after fracturing. A predictive

cubic law relating the fractured volume against injection pressure was

proposed.

Keywords: Hydraulic fracturing, In-situ recovery, copper,

geomodeling, rock mechanics, rock elastic properties, seismic wave,

permeability

Introduction

The Polish

sediment-hosted Kupferschiefer deposit is a world-class polymetallic deposit.

It extends across North-central Europe from North-Westernmost Belorussia to

Northern Ireland, along an east-westerly belt of more than 1.500 km (Vaughan et

al., 1989). Today this World Class deposit, exploited in the South-western of

Poland by KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. (Lubin, Sieroszowice-Polkowice, and Rudna

and Glogów-Glęboki-Przemysłowy mines), is placed among one of

the main Cu-Ag deposits in the World1 (~ 2% Cu and ~ 2 Oz/t Ag in over 1 Gt

bearing metals ore 2). Lead, zinc, gold, PGE, and some critical raw materials

for the EU (2011), such as rhenium, have also economic importance (KGHM, 2011).

The copper production of Poland represents half of the total copper production

in Europe (or a quarter of the total European copper consumption).

Hydraulic fracturing

implemented to the model with the view to test the in-situ mining or in-situ

recovery (ISR) method. This involves drilling of injection and recovery wells

to dissolve the deposit underground and recover the copper. Sulphuric acid is

injected using the injection well. Pumping from the recovery wells drives the

acid from central injection well to the recovery well where it is pumped back

to the surface for processing. As the acid moves through the ore body along the

natural fractures system it dissolves the oxide copper within the fractures

system.

General information about testing area

The Rudna

mine is the largest copper ore mine in Europe and one of the largest deep

copper ore mines in the world.

Rudna Mine is located in Lower Silesia, north of Polkowice city. The

mine extracts mostly “Rudna”

deposit, but it also develop and exploit parts of “Sieroszowice” and “Głogów

Głęboki-Przemysłowy” deposits. Industrial

resources of Rudna Mine (according to state on 31.12.2013) in three operated

deposits are 449 million Mg of copper ore. Average grade of copper amounts to

1,95 %, average grade of silver – 59g/Mg.

Among the Polish copper deposits operated by KGHM, Rudna deposit stands

out the thickest orebody - up to even over a dozen meters; average thickness of

Rudna deposit is over 4 meters nowadays and over 70% of resource is over 3

meters thick. In Rudna deposit the dominant part of ore is sandstone ores –

around 80% of resources, carbonate ores represent approximately 15% and

Copper-bearing shale (Kupferschiefer) only 5% of total deposit mass.

Copper-bearing Shale (Kupferschiefer) contain the highest grade of copper

– over 6% of Cu. The depth of copper orebody in Rudna deposit range from 844 m

up to 1250 m in depth, and Głogów

Głęboki-Przemysłowy deposit is up to 1385 m in depth.

Geological setting of the Kupferschiefer

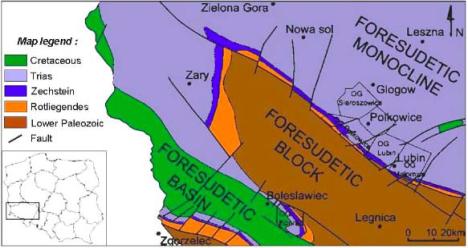

The sedimentary

formation of Kupferschiefer (literally copper shale) extends over the northern

Europe on more than 600.000 km2 (Blundell et al., 2003). The genesis of

Kupferschiefer is related to the eustatic variations of the Zechstein Sea at

the end of Permian. It is composed of a thin (< 1m) shale layer containing

in average about 7% organic matter, inserted between the Lower Permian

terrestrial/volcanic sediments (Rotliegend and Weissliegendes) and the Upper

Permian marine sediments of Zechstein (Jowett, 1986; Oszczepalski, 1999;

Blundell et al., 2003; Gouin, 2008; Borg et al., 2012; Hartsch, 2013)

Figure 1. – (a) - 3D model of the Lubin region,

Poland. The thick Zechstein evaporates confine the fluids at the basement and

interface. (b) 2D geological map of the Lubin region and mining district

exploited by KGHM (www.kghm.com).

Figure 2. In-situ recovery scheme

In-Situ

Recovery[3]

ISR is an

environmentally-friendly process by which copper can be extracted from the

ground with minimal disturbance to the surface environment (Figure 2). ISR mining has a long history, starting with

uranium mining in the 1960s.

Advantages to In-Situ Recovery Mining:

- Lower capital and

operating costs

- No waste or ore moved

- No creation of open

holes, waste dumps, leach pads or tailings

- Minimal visual

disturbance

- Minimal noise, dust

and greenhouse gas impact

- Fewer permits are

required compared to other mining processes

- More cost-effective

than most other conventional mining techniques, and thus doesn't require as

many "pounds in the ground" to make the mine economically viable

These advantages allow access to copper

deposits not amenable to conventional mining.

In-situ recovery (ISR) is a non-invasive mining

method whereby boreholes or “injection wells” are drilled into an ore-body,

through which a dilute solution is pumped to dissolve the target minerals or

metals. The solution moves through the rock in a controlled manner to nearby

recovery wells, where it is pumped back to the surface for processing.

Differential pumping rates or natural impermeable barriers are used to control

the movement of the solution through the rock. This, combined with well field

design, prevent any solution from exiting the mine area. For example, an

injection well is usually surrounded by a ring of recovery wells.

The pumping action of the recovery wells make

sure all of the pregnant solution is collected from the injection well. For

example, in ISR mining of copper oxide ores, the dissolving solution is usually

weak sulfuric, the same acid used in open pit and dump or heap leach operations

around the world. In effect, the bore holes or wells become the “mine access”

and the leach pad is “left underground”. Processing is usually done by chemical

precipitation or solvent extraction electro winning (SX-EW).

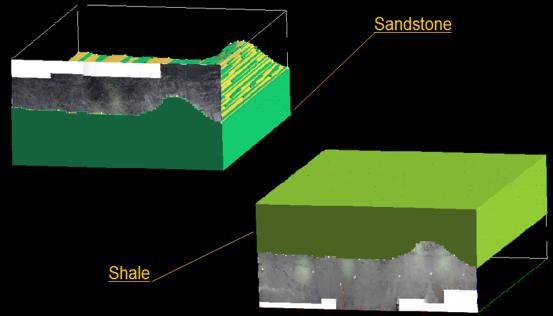

Building of 3D

reservoir model and hydraulic fracturing application

The following is the representation of creation of the

structural model of small testing area which is in Kupferschiefer deposits in

the Lubin region. The model was constructed with the purpose of performing

hydraulic fracturing on following testing area (Figure 3).

Figure 3. 3D model of testing area

The fracturing process

in gOcad provided by a special wizard developed in the gOcad environment. A

gOcad Wizard has been written by (Cosson and Chaumont, 2013) for simulating

fractures in a medium represented by a Gridded gOcad object. The mechanical

properties of the rock massif are stored in each cell, together with the

induced pressure.

So, after applying the

fracturing has been obtained the results. For better comprehension and to have

a good imagination how the fracturing process affects on permeability, the

fracturing process has been simulated several times with different values of

water initial pressure (Table 3).

Table 1. Initial

injection pressure values

|

Experiment |

Water initial Pressure (inn GPa) |

|

1 |

5 |

|

2 |

10 |

|

3 |

15 |

|

4 |

20 |

|

5 |

25 |

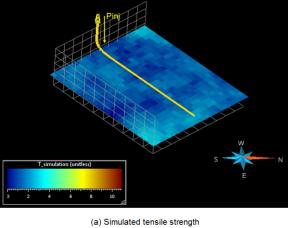

During hydraulic fracturing, when the initial injection

pressure Pinj increases,

as expected the volume of fracked rocks Vf according to a quadratic form passing

through the origin against the initial pressure according to (Figure 4):

|

|

|

(1) |

Discussion:

The fact that the fractured volume Vf reaches a maximum despite that the pressure is

increasing can be related to the Dupuit-Forchheimer radial analytical formula

used to depict the pressure P(r)

variation in the vicinity of the well. As shown in Eq.(1), when the distance r to the well increases, the pressure in

the medium is varying according to P0

/ ln(r). So the resulting pressure might not sufficient to fracture the

medium when the distance is too big. In other words, after a given pressure

sill Pmax which depends on

the nature of the rock, the fractured volume remains quite constant.

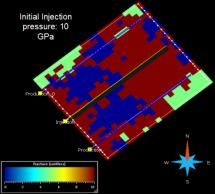

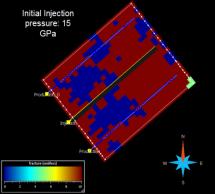

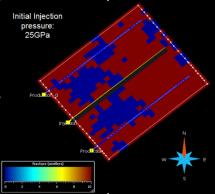

Figure

4 illustrates the results of the hydraulic fracturing with the initial

pressures (5; 10; 15; 20; 25; (GPa)), respectively. Figure 4 shows the dependence of

fracked volume on injection pressure.

Figure 4. Dependence of fracked

volume on injection pressure

The maximum fractured volume Vmax depends on the rock type; it seems that more

elastic/ductile rocks such as shale with smaller Young’s modulus E ~ 2.6 GPa,

but with higher tensile strength at T = 2.7GPa the fractured volume is lower

compared to more stiff/elastic rocks such as sandstones with higher Young’s

modulus at E ~ 5.9 GPa with tensile strength at T = 1.8GPa. More experiments

must be carried out to confirm these observations.

As shown in Figure

5, it becomes clear that the

smallest fractured volume corresponds to the lowest pressure value. The volume

of fracked medium increases with the initial pressure; the largest cracked

volume corresponding to the highest initial pressure values. The volumes of

fractured medium against the initial pressure are reported in Table 2.

Figure 5. Resulting

fractures induced by stimulation at different values of injection pressure

Table 2. Values of

fracked volume in

accordance with injection pressure

|

Water

initial pressure, GPa |

Volume

of fracked medium, m3 |

|

|

sandstone |

shale |

|

|

5 |

304.2 |

248.4 |

|

10 |

448.0 |

355.0 |

|

15 |

507.0 |

355.0 |

|

20 |

512.2 |

355.0 |

|

25 |

512.4 |

355.0 |

Permeability of

fractures

Before fracturing, the

measured permeability values were about 0.6 mD for sandstone and 0.02 mD for

shale. The above theoretical results show that they can increase to values as

high as from 0.2 to 6 mD assuming an increase factor of 10, and 2 to 60 mD for

an increase factor of 100. Fracturing really increases the permeability of

blocks. To be more precise a flow model should be applied.

Conclusions

This work investigates the way of implementation of ecologically

friendly method which is called In-Situ Recovery in Rudna copper mine site

(Poland). This method is already extensively used in uranium mines of

Kazakhstan, USA, Australia and etc. The main advantages of In-Situ recovery

(ISR) method are: no wastes, no tailings, no underground excavation, no

open-pit and etc.

Considered testing mine Rudna is located in Poland, which is the is the

largest copper ore mine in Europe and one of the largest deep copper ore mines

in the world. As the one of the optimal conditions to use ISR is that the host

rock should be fractured enough to let the solution to flow through it.

Permeability of rocks in Rudna mine is very low to implement the ISR. As the solution

of this problem the artificial way of creating fractures, i.e. hydraulic

fracturing was proposed.

Firstly, the testing site I was modeled in 3D using gOcad, rock

properties being simulated on Sgrid. Fracturing was obtained using a gOcad

wizard and assuming a transverse isotropic medium, elastic properties values

being measured in laboratory. Elastic rock properties were deduced from the

seismic Vp and Vs velocity; the permeability of the rock before fracturing is

very low at 0.7 and 0.02 mD for sandstone ans shale, respectively, increasing

to 60 and 0,2 mD after fracturing. The volume of fractured rock increases with

the injection pressure Pinj according to a quadratic form, like the surface of

the cracked medium

References

1.

Blundell, D.J., Karnkowski, P.H., Alderton, D.H.M.,

Oszczepalski, S., and Kucha, H.(2003). Copper mineralization of the Polish

Kupferschiefer: a proposed basement fault-fracture system of fluid flow.

Economic Geology 98, 1487 - 1495.

2.

Borg G., Piestrzyński, A., Bachmann, G.H., Püttmann

W., Walther S., and Fiedler, M.(2012) - An Overview of the European

Kupferschiefer Deposits. Soc.of Economic Geologists, Inc. Special Pub. 16, 455

- 486.

3.

Carl, T. M., & Michael, B. S. (2010, December). History

of an enduring technology.. (NSI Technologies ) Journal of Petroleum

Technology 2-4 p.

4.

Cosson, C. and Chaumont, A. (2013) - Shale gas and hydraulic fracturing: Wizard manual. ENSG, Nancy,

University of Lorraine, France, Master report M1, 6p.

5.

Gouin, J. (2008) - Mode de genèse et valorisation des

minerais de type black shales: cas du Kupferschiefer (Pologne) et des schistes

noirs de Talvivaara (Finlande). PhD. Thesis Report. Université

d’Orléans.

6.

Hartsch J. (2013) - Copper Mineralisation at the Zechstein

Basis in the North-Sudetic Trough and Geological Model – An Introduction. 23p.

7.

Hudson, J.A., and Harrison, J.P. (1997) - Engineering

Rock Mechanics: an Introduction to the Principles. Pergamon, Oxford, 444 p.

8.

http://www.excelsiormining.com/index.php/in-situ-recovery

9.

Jowett, E.C. (1986) - Genesis of Kupferschiefer Cu-Ag

deposits by convective flow of Rotliegendes brines during Triassic rifting.

Economic Geology 81, 1823 - 1837.

10.

KGHM (2011). Annual Report 2011. http://www.kghm.pl.

11.

Kitterod, N., (2004) - Dupuit-Forchheimer solutions for

radial flow with linearly varying hydraulic conductivity or thickness of

aquifer. Water Resources Research, 40,

1-5.

12.

Mejia, P., Royer, J.J., Fraboulet,

J.G., and Zielińska, A., (2014) - 4D Geomodeling: a Tool for

Exploration – Case of the Kupferschiefer

in the Lubin Region, Poland. Université de Lorraine, CNRS-ENSG,

Vandoeuvre-Lès-Nancy, France. 2KGHM, Cuprum Research &

Development Centre, Wroclaw, Poland, 48p.

13.

Olson, J.E. (2003) - Sublinear scaling of fracture aperture

versus length:An exception or the rule?

Journal of Geophysical Research,

108(B9), 2413-2433.

14.

Oszczepalski, S. (1999) - Origin of the Kupferschiefer

polymetallic mineralization in Poland. Mineralium Deposita 34, 599–613.

15.

Royer, J.J. (2013) - Hydraulic

fracturing in transverse isotropic media. In 33th gOcad Meeting

Proceedings, gOcad Research Group, Nancy, France, 48p.

16.

Royer, J.J. (2012) - Hydraulic

Fracturing in Homogeneous Media. In 33th gOcad Meeting

Proceedings, gOcad Research Group, Nancy, France, 20p.

17.

Robertson, E.P. and Christiansen, R.L. (2006). A Permeability for Coal and Other Fractured,

Sorptive – Elastic Media. Society of Petroleum Engineers, Eastern Regional

Meeting. October 2006. 13 p.

18.

Vaughan, D.J., Sweeney, M.A., Friedrich, G., Diedel, R., and

Haranczyk, C. (1989) - The Kupferschiefer; an overview with an appraisal of the

different types of mineralization. Economic

Geology, 84, 1003 -1027.