Musayeva K.S. -

candidate of pedagogic sciences, professor

Bekkozhanova G.H.

– candidate of philological sciences,

Abai

Kazakh National pedagogical University

Teaching foreign language through Web-Quest technology

Abstract. The Internet has become one of the most powerful tools available for

teaching virtually any subject. Some

85% of the world/s electronic information is said to be in English language [1,

50]. That makes it the potential goldmine that maó be of use for teachers for developing students’ knowledge and skills.

One of the effective strategies that can help teachers to integrate the power

of the Web with student learning is the Web-Quest strategy. Originated by

Bernie Dodge and Tom March in 1995 at San Diego University, the Web-Quest has

gained considerable attention from educators and has been integrated widely

throughout the world into curricula in secondary schools and higher education

as a way to make good use of the Internet while engaging their students in the

kinds of thinking that the 21st century requires. This paper describes the

Dodge’s model of a Web-Quest, its design process as suggested by Tom March,

provides the reasons for its use in teaching and learning process and suggests

some excellent sites to explore with the aim of helping teachers to master this effective instructional

tool.

Key

words. Web-Quest, teaching,

Introduction

A Web-Quest is an instructional tool

for inquiry- based learning in which learners interact with resources on the

Internet, develop small group skills in collaborative learning and engage in

higher level thinking. Most or all of the information used by learners is found

from pre-selected websites [2, 1]. A Web-Quest is designed to make the best use

of a learner's time, to focus on using information rather than looking for it,

and to support learners’ higher level thinking skills. In other words, students

use the Internet in such a manner that they learn not only to research

information but to use the Internet to critically think about important issues.

The key idea that distinguishes Web-Quests from other Web-based experiences is

that they are built around an engaging and doable task that elicits higher

order thinking of some kind. The thinking can be creative or critical, and

involve problem solving, judgment, analysis, or synthesis.

To

achieve its efficacy and purpose, Web-Quests should contain at least the

following parts, which are outlined by Bernie Dodge as critical components in a

Web-Quest [3, 2].

The main

part.

1.

Web-quest: purpose. The purpose of the

Introduction section of a Web-Quest is two fold: first, it's to orient the

learner as to what is coming. Secondly, it should raise some interest in the

learner through a variety of means. It can do this by making the topic seem

relevant to the learner's past experience; relevant to the learner's future

goals; attractive, visually interesting; important because of its global

implications; urgent, because of the need for a timely solution; fun, because the

learner will be playing a role or making something. When projects are related

to students’ interests, past experience, or future goals, they are inherently

interesting and exciting. For the example of an Introduction visit the Web-Quest

Creative

Problem Solving designed for ESL students at http://php.indiana.edu/~fpawan/creativestudent.html

2. A task is a formal description

of what students will have accomplished by the end of the Web-Quest. Developing

this task - or the main research question -is the most difficult and creative

aspect of creating a Web-Quest. Students can be asked to publish their findings

on a Web site, collaborate in an online research initiative with another site

or institution, or create a multimedia presentation on a particular aspect of

their research. A well designed task is doable, interesting and elicits

thinking in learners that goes beyond rote comprehension. A good example of the Task is given in the Searching

for China Web-Quest at http://www.kn.pacbell.com/

wired/China/ChinaQuest.html#Task.

3. Information Sources. This block in a Web-Quest is a list of web pages which the instructor

has located that will help the learner accomplish the task. The Resources are

pre-selected so that learners can focus their attention on the topic rather

than surfing aimlessly. Information sources might include web documents, experts

available via e-mail or real-time conferencing, searchable databases on the

net, and books and other documents physically available in the learner's

setting. Very often, it makes sense to divide the list of resources so that

some are examined by everyone in the class, while others are read by subsets of

learners who are playing a specific role or taking a particular perspective.

This can ensure the interdependence of the group and give the learners an

incentive to teach each other what they've learned. You can see an example in

the

Web-Quest Creative Problem Solving at http://php.indiana.edu/

~fpawan/creativestudent.html.

4.

Description of the process. The Process block in a

Web-Quest where the teacher provides clearly suggested steps that learners

should go through in completing the task. It may include strategies for

dividing the task into subtasks, descriptions of roles to be played or

perspectives to be taken by each learner. The instructor can also use this

place to provide learning advice and interpersonal process advice, such as how

to conduct a brainstorming session. For example, the Web-Quest Pollution and

Solutions at http://edweb.sdsu.edu/triton/

PollSol/ Week1. html.

5. Guidance provides guidance on how to organize information. This can

take the form of guiding questions, or descriptions to complete organizational

frameworks such as timelines, concept maps, or caused- effect diagrams etc.

6. Evaluation. The Evaluation block is a new addition to the Web-Quest

model. Each Web-Quest needs a rubric for evaluating students' work. Evaluation

rubrics would take a different form depending on the kind of task given to the

learner. To help teachers to deal with evaluation Dodge has developed A Rubric for Evaluating Web-Quests

which can be found at http://webquest.sdsu.edu/webquestrubric.html.It allows teachers to assign a score to a given Web-Quest and provides

specific, formative feedback for the designer.

7. Conclusion. The Conclusion section of a Web-Quest provides an opportunity to

summarize the experience, to encourage reflection about the process, to extend

and generalize what was learned, or some combination of these. It's not a

critically important piece, but it rounds out the document and provides that

reader with a sense of closure.

Results and

Findings.

Web-Quests are an inquiry-based,

learner-centered, project-based approach to teaching, learning, and information

inquiry that integrates the power of the Web with sound learning theory and

instructional design methods, such as constructivist philosophy; critical and

creative thinking questioning, understanding, and transformational learning;

scaffolding; cooperative learning; motivation and authenticity [6, 1-2].

Constructivism is a theory of teaching

and learning involves the process of questioning, exploring, and reflecting.

This theory says that learners should construct their own understanding and

knowledge of the world through varied experiences. By reflecting on these

experiences, students assimilate useful information and create personal

knowledge.

Creative thinking involves creating

something new or original. It's the skills of flexibility, originality,

fluency, elaboration, brainstorming, modification, associative thinking,

metaphorical thinking and forced relationships [1, 1].

Cooperative

learning is an approach to teaching and learning where

students work in small groups or teams to complete meaningful activities such

as solving problems or creating products. Groups share their strengths and

address their weaknesses as a team. Cooperative strategies are applied to

necessitate each student's input. As students complete more Web-Quests they will

become aware that their individual work has a direct impact of the intelligence

of their group's final product.

Student Motivation & Authenticity. Tom March points out to the following

strategies that are used in Web-Quests

to increase student motivation. First, Web-Quests use a central question

that honestly needs answering. When students are asked to understand,

hypothesize or problem-solve an issue that confronts the real world, they face

an authentic task. The second feature that increases student motivation is that

they are given real resources to work with. Rather than use a dated textbook

with the Web students can directly access individual experts, searchable

databases, current reporting, and even fringe groups to gather their insights.

Developing

Thinking Skills. One of the main features of any Web-Quest is that

student’s deal with questions that prompt higher level thinking. The question

posed to students can not be answered simply by collecting and spitting back

information. A Web-Quest forces students to transform information into

something else: a cluster that maps out the main issues, a comparison, a

hypothesis, a solution, etc. In

order to engage students in higher level cognition, Web-Quests use scaffolding

or prompting which has been shown to facilitate more advanced thinking. In

other words, by breaking the task into meaningful "chunks" and asking

students to undertake specific sub-tasks, a Web-Quest can step them through the

kind of thinking process that more expert learners would typically use.

Using

Web-Quests in our classrooms can help build a solid foundation that will

prepare our students for the future by developing a number of skills that

tomorrow’s workers will need. No one can ever learn everything, but everyone

can better develop their skills and nurture the inquiring attitudes necessary

to continue the generation and examination of knowledge throughout their lives.

For modern education, the skills and the ability to continue learning should be

the most important outcomes. And this is where Web-Quest can help use to meet

these needs.

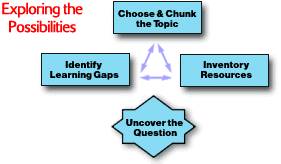

The

Web-Quest Design Process

Writing a Web-Quest is time-consuming and challenging, at least

the first time. To make this process easier for teachers Tom March developed

the Web-Quest design process which consists of three phases that are presented

below [8; 1]:

The Web-Quest Design Process. Phase 1.

Choose and chunk the topic

Choose and chunk the topic

It

is necessary to identify a topic that is worth spending time on it and one that

takes advantage of the Web and Web-Quest format. The best use of the Web-Quest format is for topics that invite

creativity and problems with several possible solutions. They can address

open-ended questions like:

-

How do other countries deal with

learning English as a foreign language, and what, if anything, can Kazakhstan

learn from them?

-

What is it like to live in a

developing country such as Kazakhstan?

-

What would Mark Twain think about

the lives that children live today?

Once

you have some ideas for topics, chunk them out into sub-categories by

clustering. You might look for things like relationships to other topics,

controversial issues, multiple perspectives about the topic, etc. This

clustering will help you when it comes time to uncover your main question and

devise roles for learners.

Inventory Resources

When teachers inventory their learning

resources they should collect all the raw materials that COULD go into their

Web-Quest. Later they will need to make choices that limit their options. In

terms of finding good Web sites, the following sites that lead to a huge number

of interesting and useful lessons, resources, and activities can be a good

starting points for exploration:

-

Education World- http://www.education-world.com/

-

Language Arts- http://www.mcrel.org/lesson-plans/index.asp

-

Foreign Language - http://www.mcrel.org/lesson-plans/foreign/index.asp

Decision:

Uncover the Question

The

single most important aspect of a Web-Quest is its Question. The Question / Task

serves to focus your entire Web-Quest and helps students engage in higher-order

thinking. It makes students look beyond the facts to how things relate, what is

the truth, how good or right something is. In writing Question / Task

Statement, Tom March suggests to consider the following things that provide

higher levels of thinking:

-

analyzing and classifying the main

parts of a topic

-

using these main parts as criteria

from which to evaluate examples of the topic

-

analyzing perspectives and opinions

through comparison / contrast

-

using an understanding of people's

opinions to make a persuasive argument

-

analyzing how things change through

cause and effect and If/Then statements

-

using if/then statements to problem

solving new situations [9, 1].

It is important to note

that this last box in this phase isn't actually a box like

the other three. This

section requires a teacher to make a decision. The decision is, "Do you

have what it takes to make a Web-Quest?" Answering the questions below

questions will help a teacher to elicit a positive response:

-

Is the Topic worth the time and

effort needed to build this Web Quest?

-

Is the level of potential student

cognition worth the effort?

-

Is a Web-Quest the right strategy?

-

Are you excited by the available

resources (both online and local)?

-

Does the Web offer so much that its

use is warranted?

-

Does the Question ask something that

people in the real world find important?

-

Is the answer to the question open

to interpretation / argument / hypothesis?

If

you've answered “Yes” to all the questions above, you're on the way to creating

a great WebQuest!

Teachers need to learn how to

effectively use the Internet to support the teaching and learning process. They

should spend time defining an information need, searching for information, and

evaluating the information before attempting to incorporate it into a lesson.

Being one of the effective strategies the Web-Quest strategy can help teachers to integrate the

power of the Web with student learning is in a way that makes sense for the New

WWW. This is because Web-Quests are found to be an activity that integrates the

power of the Web with sound learning theory and instructional design methods

and plants the seeds of change and growth so that students will internalize

some of these cognitive strategies and apply them to lifelong and self-directed

learning.

Bibliography

1. Creative and Inventive Thinking. Available: http://virtualinquiry.com/scientist/creative.htm.

2. Dodge B. Active learning on the

web. Available: http://edweb.sdsu.edu/people/bdodge/active/ActiveLearningk-12.html,

1996.

3. Dodge B. WebQuest rubric.

Available: http://webquest.sdsu.edu/webquestrubric.html, 2001.

4. Dodge B. WebQuest.org. Available: http://webquest.org,

2004.

5. March T. Working the web for

education: Theory and practice on integrating the web for learning. Updated

2001. Available: http://www.ozline.com/learning/theory.html, 1997.

6. March T. Why WebQuests? Updated

January 6, 2004. Available:

7.

http://www.internet4classrooms.com/why_webquest.htm, 1998.