Student

Nechay V., Ph.D. Kovalenko M.

National Technical University of Ukraine «Kyiv

Polytechnic Institute», Ukraine

The theoretical basis for the development of the field of

mathematical models of electrical machines

Lumped parameters are matrices describing

electromagnetic properties such as resistance, capacitance, and inductance. In

the time-harmonic case the lumped

parameter matrix is either an impedance matrix or an admittance matrix

depending on how the model is excited (current or voltage). In a static

calculation only the resistive, capacitive, or inductive part of the lumped

parameter matrix is obtained.[1] To

calculate the lumped parameters, there must be at least two electrodes in the

system, one of which must be grounded. Either a voltage or a current can be

forced on the electrodes. After the simulation, extract the other property or

the energy and use it when calculating the lumped parameter.

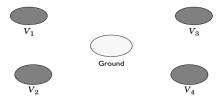

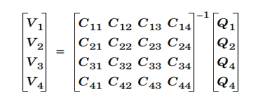

There are several available techniques to extract the lumped parameters. Which

one to use depends on the physics interface, the parameter of interest, and how

the model is solved. The overview of the techniques in this section use a

4-by-4 matrix example for the lumped parameter matrix. This represents a system

of at least five electrodes, where four are used as terminals and the rest are

grounded, as illustrated in Figur 3-2.[1]

251658240

Figure 3-2: A five-electrode system with 4

terminals and one ground electrode.

If a system specifies that all electrodes

are terminals, the results are redundant matrix elements. This is better

understood by considering a two-electrode system. If both electrodes are

declared as terminals, a 2-by-2 matrix is obtained for the system. This is

clearly too many elements because there is only one unique lumped parameter

between the terminals[2]

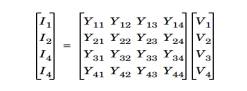

Forced voltage

If

voltages are applied to the terminals, the extracted currents represent

elements in the admittance matrix, Y. This matrix determines the

relation between the applied voltages and the corresponding currents with the

formula[3]

251658240

so

when ![]() is nonzero and

all other voltages are zero, the vector I

is proportional to

is nonzero and

all other voltages are zero, the vector I

is proportional to

the first column of Y.

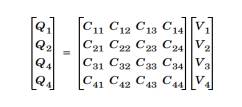

In electrostatics the current is replaced with charge and the admittance matrix

is

replaced with the capacitance matrix

251658240

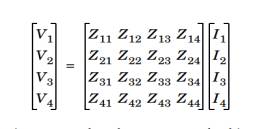

Fixed current

It might be necessary to calculate the Z-matrix in a more direct way. Similar

to the Y calculation, the Z calculation can be done by forcing

the current through one terminal at the time to a nonzero value while the

others are set to zero. Then, the columns of the impedance matrix are

proportional to the voltage values on all terminals[4]:

251658240

In magnetostatics this option means that

the energy method is used; see Calculating Lumped Parameters Using the Energy

Method below.

Fixed

charge

The Electrostatics interface can use total

charge instead of total current. This gives the inverted capacitance matrix in

a similar manner as the Z and Y matrices.

251658240

Studing

Lumped Parameters

To study lumped parameters, use the

terminal boundary condition for each electrode.

This boundary condition is available in the following interfaces and the

methods

described in the previous section are used to calculate the lumped parameters[4]:

• Electrostatics. Uses

a stationary study and the energy method.

• Electric Currents.

Uses a stationary or frequency domain study type using the method based on

Ohm’s law.

• Magnetic and Electric

Fields. For the stationary study the energy method is used. For the frequency

domain study type, the method based on Ohm’s law is used.

References:

1. Jianming Jin, The Finite Element Method in

Electromagnetics, 2nd ed.,

Wiley-IEEE Press, May 2002.

2. O. Wilson, Introduction to Theory

and Design of Sonar Transducers, Peninsula Publishing, 1988.

3. R.K. Wangsness, Electromagnetic

Fields, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, 1986.

4. D.K. Cheng, Field and Wave

Electromagnetics, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley, 1991.