Tagiev Sanan Mehman oglu

Kuzbass State Technical University, Kemerovo

Economic overview coal to liquids

technologies

In

absolute terms, CTL will be expensive to build and expensive to run. Therefore,

it will only be deemed worthwhile proceeding if concerns about the security of

oil and gas supplies are such that substitute oil products via CTL can provide

a level of reassurance at a price that is deemed worth paying. As with all

‘insurance policies’ this will always seem unnecessary until it is actually

needed. Also, as with all insurance policies, under-investment or failure to

pay the premiums will mean that benefits will not be paid out when they are

needed [1].

CTL,

by whichever route, is capital-intensive and therefore benefits substantially

from economies of scale. Most studies on process economics have assumed that a

full-scale commercial plant would produce 50,000-100,000bbl/day of liquid

products . Such a plant would process 15,000-35,000 tonnes/day of bituminous

coal or up to double that amount of sub-bituminous coal or lignite.

Sasol

have stated that their prerequisites for contracting with an organization to

proceed with a CTL FT plant would be assume a minimum plant size of 80,000

bbl/day, to take advantages of the economies of scale. At the same time, access

would be needed for to up to 400 million tonnes of coal over the project

lifetime. This would most likely be ‘stranded coal’ due to its low-quality or

location, making it unsuitable for alternative applications, such as

electricity generation.

Of

equal importance would be the need for government support for the very large

capital investments, on the grounds of improved energy security through

decreased dependence on imported energy, and to shield developers from oil

price volatility. In late 2006, the likely cost of such a plant was given as

US$ 5-6 billion with annual operating costs of some US$ 250 million [2].

In

2006, the IEA noted that for CTL to be competitive, a plant would need to have

access to coal at less than 20 US$/t. Although this is less than half of the

current international price, over 80% of the world’s coal is not

internationally traded, and at least 30–40% of the world’s coal is mined for

less than 20 $/t - including most low rank coals. On that basis, at a steam

coal price of 20 US$/t, CTL can be competitive with a crude oil price of under

40 US$/bbl, and the average production cost of synfuels would be about 50

$/bbl. There will be economies and cost reductions associated with the building

of a series of CTL plants as operational experience is gained and the initial

designs are copied and refined.

MIT

examined the possible impact of including CCS on a CTL unit. In broad terms,

the capital cost of a synthetic fuels production facility would be around

$53,000 per bbl/d of liquids output with no CO2 capture. This would

increase to $56,000 per bbl/d with CO2 capture. This assumes a

20-year plant life, a three-year construction period, and a 15.1% capital

carrying charge factor on the total plant cost, a 50% overall thermal

efficiency for the FT plant, and a 95% plant capacity factor. Using these

factors, the production cost of FT fuels is estimated to be 50 $/bbl without

CO2 capture (similar to the IEA estimate) and 55 $/bbl with CO2

capture [3].

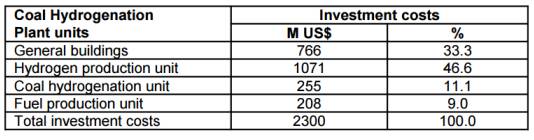

Table

1. Modified investment costs structure for 1 Mt fuels per year plant

Table

1. Modified investment costs structure for 1 Mt fuels per year plant

In Poland, the investment costs for industrial coal

hydrogenation plant were estimated in the 1970s and 1980s by GBSiPPW SEPARATOR.

In 2006, these estimates were updated at the Central Mining Institute, based on

the indices of the cost of apparatus and equipment, and on indices of investment

cost increases in the chemical industry (Chemical Engineering Archive

1979–2005). The investment cost for a plant of 1 Mt per year of coal-based

liquid fuels, recalculated for 2006 is 2.8 billion US $ (± 30%).

Analysis of the investment costs structure showed that

the cost of the hydrogen production unit is much higher than those of the coal

hydrogenation and fuel production units. This is due to the assumed

postreaction residue separation by low temperature carbonization and hydrogen

production in the Winkler reactor. An application of new technologies,

industrially proven over the last twenty years, such as supercritical

post-reaction residue separation and advanced gasification processes for coal

and residue – based hydrogen production, should decrease the investment costs

for hydrogen production.

Based on the literature and material balance data,

economic estimates for a modified concept of the Coal Liquefaction Plant CMI

2006 (CMI 2006) producing 1 and 3 million tonne of liquid fuels (gasoline and

diesel oil) were prepared. The calculations were carried out for two coal price

levels of 54 US$/t (Poland) and 20.5 US$/t (China). The modified investment

cost structure for the 1 Mt per year plant is given in Table 1.

This analysis allows an evaluation of the impact of

coal price and plant production capacity on the basic economic indicators of

the plant (required product market price and required crude oil market price)

to ensure that the required product price selling price can be met. The

calculations were carried out for 2006 prices using simplified economic models

based on indices given in DTI, 1999.

As can be seen, the production capacity and coal price

are key to the economics of a coal liquefaction plant. For a plant producing 3

Mt of liquid fuels per year, assuming a coal price below 54 US$/t, the required

selling price for liquid fuels produced is within the range of prices met by

refineries processing crude oil of the price level of 44 US$/bbl, while for a

plant of capacity of 1 Mt of liquid fuels per year, the limiting crude oil

price is 63 US$/bbl [4].

Production of 3 Mt of fuels per year would increase

the share of coal – based fuels in the total fuel consumption in the transport

sector in Poland. For example, the production of coal hydrogenation plant would

cover 34% of the amount of engine fuels used by the transport sector in 2005.

Assuming an annual increase in fuel consumption of 1%, the production level

would satisfy 27% of the transport sector demand in 2030. This suggests that

the development of such plant would strengthen the national energy independence

in terms of engine fuels in a longer time perspective.

The key point is that the results of these various

studies are consistent with each other and show that the production of liquid

fuels from coal is broadly economic, given the range of oil prices to be

expected over the coming decades. When the security of energy supplies is also

taken into consideration, CTL to provide transport fuels becomes an attractive

proposition providing that there is enough coal available to make sufficient

quantities of the required fuels.

Bibliography:

1.

Tagiev

S. M. Coal to liquid technologies in the World and development prospects in

Australia // Materials of XI International Research and Practice Conference. – Sheffield

UK, 2015

2.

Parker D. Brown

coal to diesel a world first in scale. The Australian.

www.theaustralian.news.com.au. 28.04.2007

3.

Kavelov B.,

Peteves S. D. The Future of Coal, EUR

22744 EN, ISBN 978-92-79-05531-7, ISSN 1018-5593 Luxembourg: Office for

Official Publications of the European Communities, European Commission, 2007

4.

Euracoal (2005)

Coal Industry across Europe 2005. Euracoal, Brussels