Ïåäàãîãè÷åñêèå íàóêè/Ñîöèàëüíàÿ ïåäàãîãèêà

Õîìåíêî Ë.Ì.

Ñóìñüêèé Íàö³îíàëüíèé Àãðàðíèé Óí³âåðñèòåò, Óêðà¿íà

Students’ motivation as the key to academic

success

Teachers and educators

all over the world nowadays are facing the challenge of how to motivate the

students entering colleges

and universities who are often

psychologically, socially, and academically unprepared

for the demands of student

life. Education

programs, however, do not address the whole problem. Lack of

motivation is not limited to the academically weak student. Successful remedial

and study strategies courses aimed at the underprepared student have

demonstrated that students who really want to improve their skills can do so

when motivated. However, even the best curricula have failed to positively impact the

student who is both underprepared academically and unmotivated. When students

have both a lack of academic skills and lack motivation, the greater problem is

motivation [5]. Faculty often have neither the time nor inclination to address difficult

motivational issues in the classroom, consequently, the task of trying to

effectively motivate such students often falls to academic advisors. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to give a general

understanding of student motivation, to analize the factors influencing it and

find the most effective ways to get them excited about learning.

Opinions

about the role of motivation in academic achievement and what can be done about

it vary widely among college faculty, administrators, and student services

professionals. Consideration about unmotivated students opens a Pandora’s box

of questions: Can anything be done about these students? Can motivation be

taught? What kind of strategies can be used to influence motivation? Is this

time wasted that might better be used on those students who are already

motivated? The problem of

devising effective strategies that influence motivation relies initially on the

identification of specific motivational factors. The histories of psychology

and education are abundant with research on motivation and its effect on

behavior. The study of motivation in education has undergone many changes over

the years, moving away from reinforcement contingencies to the more current

social-cognitive perspective emphasizing learners’ constructive interpretations

of events and the role that their beliefs, cognitions, affects, and values play

in achievement[8].

“There are three things

to remember about education. The first is motivation. The second one is

motivation. The third one is motivation.” (Former U.S. Secretary of Education

Terrel Bell). Practice shows that the

best lessons, books, and materials in the world will

not get students excited about learning and willing to work

hard if they are not motivated.

A student may arrive in class with a certain degree of

motivation. But the teacher's behavior and teaching style, the structure of the

course, the nature of the assignments and informal interactions with students

all have a large effect on student motivation. We may have heard the

utterance, "my students are so unmotivated!" and the

good news is that there is

a lot that we can do to change that. Because learners have different

purposes for studying, it is important for instructors to identify students'

purposes and needs and develop proper motivational strategies. Students should

understand why they need to make an effort, how long they must sustain an

activity, how hard they should pursue it, and how motivated they feel toward

their pursuits.

Motivation, both

intrinsic and extrinsic, is a key factor in the success of students at all

stages of their education, and teachers can play a pivotal role in providing

and encouraging that motivation in their students. They say, “It is easier said

than done”, as all students are motivated differently and it takes time and a

lot of effort to learn to get your students enthusiastic about learning,

working hard.

What Is Student Motivation?

Numerous cross-disciplinary theories have been suggested to explain

motivation. While each of these theories has some truth, no single theory seems

to adequately explain all human motivation. The fact is that human beings in

general and students in particular are complex creatures with complex needs and

desires. With regard to students, very little if any learning can occur unless

students are motivated on a consistent basis. The five key ingredients

affecting student motivation are: student, teacher, content, method/process,

and environment.Motivation is defined as the act or process of motivating; the

condition of being motivated; a motivating force, stimulus, or influence;

incentive; drive; something (such as a need or desire) that causes a person or

student to act [7]. Some theories claim

that people or students are motivated by material rewards, desire to increase

their power and prestige in the world, interesting work, enriched environments,

recognition, or being respected as an individual. Each of these theories has

some truth but no single theory seems to adequately explain all human

motivation.According to

Jere Brophy, a leading researcher on student motivation and effective teaching,

“Student motivation to learn is an acquired competence developed through

general experience but stimulated most directly through modeling, communication

of expectations, and direct instruction or socialization by others (especially

parents or teachers).” [1].

Student motivation

naturally has to do with students' desire to participate in the learning

process. However, it also concerns the reasons or goals that underlie their

involvement or noninvolvement in academic activities. Although students may be

equally motivated to perform a task, the sources of their motivation may

differ.

The question of what motivates

students’ behavior in achievement contexts is one of long-standing interest to

psychologists and educators. Much of the research in this area has classified

motivation as either intrinsic (i.e., inherent to the self or the task) or

extrinsic (i.e., originating from outside of the self or the task). That is,

students are often thought to be learning either for the sake of learning or as

a means to some other end, whether it be praise, good grades, etc. A student

who is intrinsically motivated undertakes an activity

"for its own sake, for the enjoyment it provides, the learning it permits,

or the feelings of accomplishment it evokes"[6]. An extrinsically motivated

student performs "in order to obtain some reward or avoid some punishment

external to the activity itself," such as grades, stickers, or teacher

approval. Numerous research studies have shown that intrinsically motivated

students have higher achievement levels, lower levels of anxiety and higher

perceptions of competence and engagement in learning than students who are not

intrinsically motivated. However, every

student is not and cannot be always intrinsically motivated towards certain

tasks. The majority of researchers believe that motivation is not exclusively

intrinsic or extrinsic in orientation.A balanced pedagogical approach in the

classroom includes the combination of both types [3].

Several specific motivational factors have come to

light in recent educational research from the social cognitive approach

including: Intrinsic Goal Orientation, Extrinsic Goal Orientation, Task Value,

Control of Learning Beliefs, and Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance.

These factors are defined as:

Intrinsic Goal Orientation is having a goal orientation toward an academic

task that indicates the students' participation in the task is an end all to

itself rather than participation being a means to an end. Also included here is

the degree to which students perceive themselves to be participating in a task

for reasons such as challenge, curiosity, and mastery [2].

Extrinsic Goal Orientation concerns the degree to which students perceive

themselves to be participating in a task for reasons such as grades, rewards,

performance evaluation of others and competition. Students with high in

extrinsic goal orientation engage in learning tasks as the means to an end. The

main concern here is the students with high Extrinsic Goal Orientation relate

to issues rather than those directly related to participating in the task

itself [2].

Task Value refers to students' evaluation of how

interesting, how important, and how useful the task is. High task should lead

to more involvement in learning. Task value refers to the students' perceptions

of the course material in terms of interest, importance, and utility[2].

Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance comprises two aspects of expectancy: expectancy

for success and self-efficacy. Expectancy for success refers to performance

expectations, and relates specifically to task performance. Self-efficacy is a

self appraisal of one's ability to accomplish a task and one's confidence in

possessing the skills needed to perform that task [2].

Test Anxiety has been found to be negatively related to

expectancies as well as to academic performance. Test anxiety is thought to

have two components: a worry, or cognitive component, and an emotional

component. The worry component refers to students' negative thoughts that

disrupt performance, whereas the emotionality component refers to affective and

physiological arousal aspects of anxiety. Cognitive component and preoccupation

with performance have been found to be the greatest sources of performance

decrement. Training in the use of effective learning strategies and test-taking

skills should help reduce the degree of anxiety [2].

These

factors identified in the social-cognitive model of motivation can be narrowed

to three motivational constructs: expectancy, value, and affect. The expectancy

construct assesses perceptions of self-efficacy and control beliefs of

learning. The self-efficacy construct postulated by Bandura in his social

learning theory has guided extensive motivational research. The second

construct of expectancy is a refined construct based on Rotter’s locus of

control. Rotter’s locus of control construct, first presented in 1966, is

perhaps one of the most highly researched concepts in modern psychological

study. The value construct includes intrinsic and extrinsic

goal orientation as well as task value beliefs. Ryan, Connell, and Deci (1985)

who researched the role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in their

“Cognitive Evaluation Theory” argue that perceptions of autonomy and competence

are fundamental to intrinsic motivation. Commitment to educational attainment

and learning are necessary to sustain motivation. Commitment to learning is a

syndrome of variables such as belief in the value of learning.The third

motivational construct is affect and can be measured in terms of test-anxiety.

A meta-analysis of 562 studies that related test anxiety and academic

achievement found that test anxiety does cause poor performance, is negatively

related to self-esteem, and is directly related to students’ fear of negative

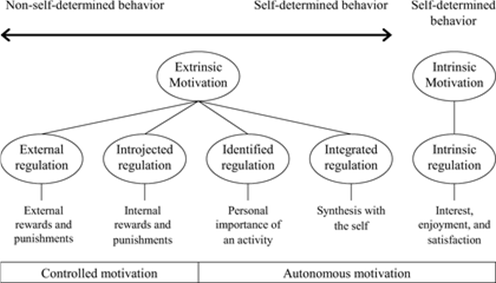

evaluation [4]. Ryan and Deci (2000) proposed a Self Determination Theory (SDT) in order to make the critical distinction between behaviors that are volitional and

accompanied by the experienceof freedom and autonomy. They

propose that some types of extrinsic

motivations are weak, whereas, some are active and agentic

states. They describe different forms of extrinsic motivation as a continuum

starting from a motivation

(not motivated); to external regulation (where a

task is attempted to satisfy an external demand); introjected regulation

(a task is done for ego enhancement); identification (where the task is valued

for itself) and integrated regulation which is the most autonomous kind of extrinsic motivation and

exists when external regulations are fully assimilated in a person's self

evaluations and beliefs of their own

personal

needs. Understanding

the different types of extrinsic

motivation

is very important

as the types of extrinsic motivations show how much a student is self determined during a learning task

and also shows the quality of effort he or she is putting into a task.

Figure.

Ryan and Deci’s Self Determination Theory Model

Students display more motivational benefits from teachers they like over

teachers they dislike. The following

suggestions are offered regarding teacher contributions to student motivation:

- Subject knowledge and motivational level: The professor’s knowledge

of the subject matter and the motivational level of the professor are most

important to motivate college students to do well in college. That may be

because professors could influence the student’s internal state of wanting

to do well in college.

- Teacher skills: One important extrinsic factor in the educational

environment is the instructor. Teacher skills include staying calm,eliminating negative thoughts

or feelings, disengaging stress, remembering that students have their own

realities and are doing their best, not taking students’ actions

personally, remembering that students are not bad rather just in the

process of development, and maintaining a sense of humor.

- Teacher qualifications: Qualifications of the teacher employed in

universities should be questioned and improved. Educators need to acquire

new qualities and continue to grow and evolve, as they are role models for

the students.

- Test giving: Teachers need to know how to give tests that are

motivating to the students. In general, test-taking instructions,

terminology, layout, and item choices need not to be ambiguous, confusing,

illogical, unclear, imprecise, or poorly designed.

- Scientific management and human relations: The educator must

consider whether to approach students from the viewpoint of scientific

management, human relations, or both. Here are some tips on how to add

components of both scientific management and human relations:

− Use inventive

teaching techniques,

− Encourage your

students to embrace technology,

− Make learning both

interesting and entertaining,

− Require significant

effort both inside and outside the classroom,

− Convey a real sense

of caring to the students,

− Make each student

feel special,

− Help students

outside of the classroom and at odd hours,

− Teach them how to

use information to make proper decisions for real life,

− Students need to

know you are approachable,

− Motivate them to

achieve at their maximum level,

− Instill a fire in

your students,

− Go beyond the

confines of the academic setting,

− Discuss contemporary

topics,

− Share personal

relevant experience,

− Capture the interest

of your students,

− Be devoted to your

students,

− Learn students’ individual

needs and respond appropriately,

− Develop specialized

assignments and schedules when needed,

− Provide tools for

their careers,

− Promote practical

work experience,

− Foster relationships

with local area professionals,

- Know your students and build on their strengths:

Use the

strengths that students bring to the classroom.

- Value and build relationship:

Some of the

necessary elements that build and maintain constructive relationship

include trust, be on their side, treat everyone with respect all of the

time, be in charge and lead them to achievement, work together, and show

you can listen and accept what the student says.

- Enthusiasm: When the teacher is more enthusiastic about a topic,

then the students will be more inclined to believe that the topic has

value for them. That is, teacher enthusiasm can motivate students.

Enthusiasm can be expressed by facial expressions, body language, stating

preferences, describing personal experiences or amazing facts, showing

collected artifacts, using humor, putting energy into their lesson

preparation, and meticulously preparing materials.

Here are five effective ways to get your students

excited about learning:

1. Encourage Students

Students look to teachers for approval and positive

reinforcement, and are more likely to be enthusiastic about learning if they

feel their work is recognized and valued. You should encourage open

communication and free thinking with your students to make them feel important.

Be enthusiastic. Praise your students often. Recognize them for their

contributions. If your classroom is a friendly place where students feel heard

and respected, they will be more eager to learn. A “good job” or “nice work”

can go a long way.

2. Get Them Involved

One way to encourage students and teach them responsibility

is to get them involved in the classroom. Make students work in groups and

assign each a task or role. Giving students a sense of ownership allows them to

feel accomplished and encourages active participation in class.

3. Offer Incentives

Setting expectations and making reasonable demands

encourages students to participate, but sometimes students need an extra push

in the right direction. Offering students small incentives makes learning fun

and motivates students to push themselves. Incentives can range from small to

large giving a special privilege to an exemplary student, to a class pizza

party if the average test score rises. Rewards give students a sense of

accomplishment and encourage them to work with a goal in mind.

4. Get Creative

Avoid monotony by changing around the structure of

your class. Teach through games and discussions instead of lectures, encourage

students to debate and enrich the subject matter with visual aids, like

colorful charts, diagrams and videos. You can even show a movie that

effectively illustrates a topic or theme. Your physical classroom should never

be boring: use posters, models, student projects and seasonal themes to

decorate your classroom, and create a warm, stimulating environment.

5. Draw Connections to Real Life

“When will I ever need this?” This question, too often

heard in the classroom, indicates that a student is not engaged. If a student

does not believe that what they are learning is important, they will not want

to learn, so it is important to demonstrate how the subject relates to them.

It is a well-known fact that

motivation fluctuates, and it is challenging to keep language learners'

motivation at a high level all the time. When designing a language course,

teachers must take into consideration that each learner has different interests

and expectations. The following strategies are effective ways to

increase language learners' external motivation.

1) Create a Friendly Atmosphere in the Classroom

Develop a friendly climate in which all students feel

recognized and valued. Many students feel more comfortable participating in

classroom activities after they know their teacher and their peers.

2) Create Situations in Which Students Will Feel a

Sense of Accomplishment

A sense of accomplishment is a great factor in

motivating students. Be sure to give positive feedback and reinforcement. Doing

so can increase students' satisfaction and encourage positive self-evaluation.

A student who feels a sense of accomplishment will be better able to direct his

or her own studies and learning outcomes. Positive as well as negative comments

influence motivation, but research consistently indicates that students are

more affected by positive feedback and success. Praise builds students'

self-confidence, competence, and self-esteem.

3) Encourage Students to Set Their Own Short-Term

Goals

Language learners can achieve success by setting their

own goals and by directing their studies toward their own expectations.

Students can help themselves achieve their goals by determining their own

language needs and by defining why they want to learn the language. Having

goals and expectations leads to increased motivation, which in turn leads to a

higher level of language competence. We as teachers should encourage students

to have specific short-term goals such as communicating with English speakers

or reading books in English. No matter what these goals are, we should help

students set and pursue them.

4) Provide Pair and Group Activities to Develop

Students’ Confidence

Students learn by doing, making, writing, designing,

creating, and solving. Passivity decreases students' motivation and curiosity.

Small-group activities and pair work boost students' self-confidence and are

excellent sources of motivation. Group work can give quiet students a chance to

express their ideas and feelings on a topic because they find it easier to

speak to groups of three or four than to an entire class.

5) Connect Language Learning to Students' Interests

Outside of Class

In today’s high-tech

learning environment, it would be unfair to limit students to traditional

methods. Encouraging students to relate their classroom experience to outside

interests and activities makes developing language skills more relevant. For

example, computer-assisted language learning could be linked to playing

computer games, or to computer programs that the students are interested in

using. Listening to English language songs, watching English language films or

videos, and reading English language Web sites can lead students to broaden

their perspective on their language acquisition process.

To sum it up, motivational

teaching strategies such as these can easily increase language learners'

motivation levels. The idea that student motivation is a personality trait and

that students are either motivated or unmotivated is incorrect. Without

sufficient motivation, even individuals with the most remarkable abilities

cannot achieve their long-term goals. As instructors, we may be the most

important factor in influencing our students' motivation, which is a key

element in the language acquisition process.

References:

1. Brophy, Jere. Synthesis of Research on Strategies

for Motivating Students to Learn. Educational Leadership 45(2): 40-48.

2. Garcia, T., McKeachie,

W. J., Pintrich, P. R., & Smith, D. A. (1991). A manual for the use

of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (Tech. Rep. No.

91-B-004). Ann Arbor, MI : The University of Michigan, School of Education.

3.Harackiewicz, J. M., & Sansone, C. (2000). Rewarding competence: The importance of goals in the

study of intrinsic motivation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic

and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance. San

Diego, USA: Academic Press.

4. Hembree, R. (1988).

Correlates, causes, effects, and treatment of test anxiety. Review of

Educational Research, 58, 47-77.

5. Kelly, D.K. (1988). Motivating the

underprepared unmotivated community college student. Viewpoints (120)

– Information analyes (070).

6. Lepper, Mark R. "Motivational Considerations

in the Study of Instruction." Cognition and Instruction 5, 4 (1988):

289-309.

7. Merriam-Webster (1997). Merriam-Webster’s

Dictionary, Houghton-Mifflin.

8.Pintrich, P. R., &

Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education.Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.