Dukhinova M.S., Lipina T.V., PhD,

Pogodina L.S., PhD

Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia

Analysis of age-dependent changes in myocardium of Japanese quail

BACKGROUND

Cardiovascular

diseases are the leading reason of human death all over the world (2, 4). Heart

aging – one of the main factors in their developing – is rather well studied

only in mammals. Birds are often used in embryonic development research but

there is lack of information about their aging (1). Mammalian and avian hearts

have similar anatomy structure but avian heart is bigger due to body weight (3).

It is an obvious advantage of the model. Moreover, avian cardiomyocytes

constantly undergo the mechanical stress because of their faster heart rate (7).

Japanese quails, Coturnix japonica,

are also characterized by natural accelerated aging and can become one of the

promising model objects in gerontology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Japanese

quails (males and females) 9-12 (young) and 48-52 (old) weeks old (from Emanuel

Institute of Biochemical Physics RAS) were used in our research. The left-ventricle

myocardium’s tissue samples were prepared for light and transmission electron

microscopy studying. The cardiomyocyte size, number of blood capillaries per

one cardiomyocyte and apoptotic death level (by Tunel method) were analyzed at

thick sections. Volume of myofibrils, mitochondria and lipid drops, number of

long mitochondria and intermitochondrial contacts (criteria of functional heart

muscle overload, (5)) were measured using electron-microscopy method. The data

were analyzed by Statistica 5.5 (Mann-Whitney nonparametric U-test, ð˂0,05).

RESULTS

AND DISCUSSION

Light-microscopic

analysis revealed that Japanese quail’s cardiomyocytes are long narrow cells

about 3 µm in diameter with thin sheets of connective tissue between them. The

number of blood capillaries per one cardiomyocyte is 0,86. These parameters

were at the same level in birds of both analyzed age groups.

Although

no evidence of hypertrophic changes was found during light-microscopic

research, the level of apoptotic cell death is increasing in two times during

the studied period of quail life. The influence of cardiomyocytes’ shortage can

be already seen on electron-microscopy level.

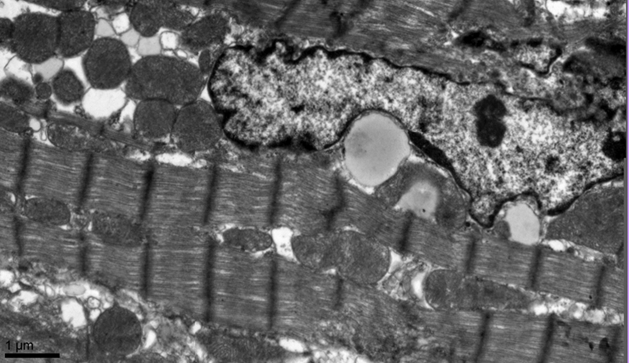

Electron-microscopic

analysis revealed the nucleus of Japanese quail’s cardiomyocyte is situated in

center and has elongate form and invaginated borders. The main part of

cytoplasm (up to 70%) is occupied by myofibrils that organized in parallel

rows. In old quails’ cardiomyocytes this type of myofibrils’ organization is

sometimes damaged. From 9 to 52 weeks of life myofibrils volume is significantly

decreased. However, the particular zones where contractile apparatus is

hypertrophied can be seen in cells of old birds.

Picture 1. Cardiomyocyte of 9 weeks old

Japanese quail

Mitochondria

are localized between myofibrilar rows and in perinuclear region; their volume

is 30% of cytoplasm at the average. The mitochondria’s volume is significantly increased

in the cells of 52 weeks old birds. So, the mitochondria/myofibrils ratio is

shifted to mitochondria in old birds’ heart, comparing with younger ones.

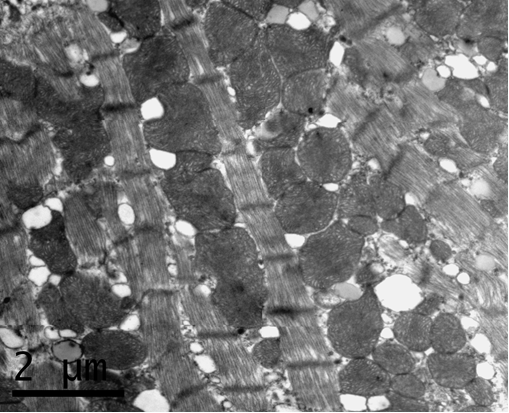

Due

to localization, mitochondria are divided into two groups, or populations:

interfibrilar and perinuclear mitochondria. These organells differ by its size

and shape. Perinuclear mitochondria are mostly not very big, round- or

oval-shaped organells. In interfibrilar zone long and large ones can be seen,

but not very often. We account mitochondrion as long if it is more than 2 µm in

length. It can be clearly seen that large mitochondria are formed by fusion of

the usual organells.

Picture 2. Cardiomyocyte of 52 weeks

old Japanese quail

The

senescence-connected structural and functional alterations of mitochondria can

be seen on electron-microscopy level. First of all, the number density of long

mitochondria increased by 60% from 9 to 52 weeks age. The longest

mitochondrion’s profile measured in young cardiomyocytes is 3,3 µm and runs to

6,6 µm in the old ones.

Age-related changes have different

influence on number of intermitochondrial contacts in interfibrilar and

perinuclear zones. No changes are marked in the interfibrilar population of

mitochondria. At the same time in the perinuclear zone we can see the increase

of intermitochondrial contacts’ number from 9 to 12 weeks and decrease of its

quality to 52 weeks of age back to the level of 9 week-old group.

Both

in interfibrilar and perinuclear zones lipid drops and lipofuscin granules can

be seen.

Lipofuscin

granules can be detected in cardiomyocytes of young and old quails, but its

quality significantly increases in old birds. This

fact corresponds well to data mentioned earlier for aging in humans (8) and in

rodents (6). Lipofuscin granules in quail’s

cardiomyocytes are heterogeneous, electron-dense structures of different shape

and size.

The

volume of lipid drops increases on 40% during studied period of life. This

fact, together with mentioned above mitochondria changes, are likely to indicate

alterations in cell energy metabolism during quail life.

So,

we found that quail myocardium of 48-52 weeks old birds (old), in comparison

with 9-12 weeks old, have several differences: increased number of apoptotic

cells; increased mitochondria/myofibril ratio, increased number of long

mitochondria, higher level of lipid drops volume and lipofuscin granules

quality in cardiomyocytes of old heart. All mentioned changes were the same for

males and females - we found no sexual distinctions in aging process in quail

myocardium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We

thank Dr. Pavel P. Zak and employees of Laboratory of Photo-Chemical Bases of

Reception, Emanuel Institute of Biochemical Physics RAS, for provided research

material and assistance in experiments realization.

REFERENCES

1. Henk P. J. Buermans, Bram van Wijk, Margriet A. Hulsker, Niels C. H. Smit,

Johan T. den Dunnen, Gertjan B. van Ommen, Antoon F. Moorman, Maurice J. van

den Hoff, Peter A. C. ’t Hoen. Comprehensive Gene-Expression Survey Identifies

Wif1 as a Modulator of Cardiomyocyte Differentiation. PLoS ONE |

www.plosone.org December 2010 | Volume 5 | Issue 12 | e15504

2. Dao-Fu Dai and Peter S. Rabinovitch. Cardiac Aging in Mice and Humans:

the Role of Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009 October;

19(7): 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2009.12.004.

3. Rumyantsev P.P. Cardiomyocytes in reproduction, differentiation and

regeneration. “Nauka”, 1982.

4. H. Shih, BA, B. Lee, BA, R. J. Lee, MD, PhD, and A. J. Boyle, MBBS, PhD.

The Aging Heart and Post-Infarction Left Ventricular Remodeling. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 2010 December 28; 57(1): 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.623.

5.

Shornikova M.V. Intermitochondrial

contacts in cardiomyocyte mitochondriom in norm, under physiological overload

and in pathology. Onthogenesis. – 2000. - ¹ 6. – Pp. 470-475

6.

J. N. Skepper and V. Navaratnam.

Lipofuscin formation in the myocardium of juvenile golden hamsters: an

ultrastructural study including staining for acid phosphatase. J. Anat. (1987), 150,

pp. 1554167

7. David B. Slautterback, Ph.D. Mitochondria in cardiac muscle cells of the

canary and some other birds. The Journal of Cell Biology, Volume 4, 1965.

8. Strehler BL, Mark DD, Mildvan AS. GEE MV: Rate and magnitude of age

pigment accumulation in the human myocardium. J Gerontol. 1959 Oct; 14:430-9.