Omorov T.M.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF CEREBRAL ECHINOCOCCOSIS

INTRODUCTION

Echinococcosis is a widely as distributed

disease of low prevalence. The problems are not so much the numbers of

patients, but the fact is hat the disease is highly pathogenic in affected

patients. In the literature, between 43%-66% of cases present as liver disease,

32%-37% as pulmonary disease, 13,6% as concurrent pulmonary and liver disease,

with 0,2% involving the lungs, liver and brain. (Akmatov 1994, Akshulakov et al

2000, Akhunbaev 1964, Kornyansky et al 1968, Petrovsky et al, Rosin 1991,

Jimenes-Mejias et al 1991).

The prognosis for patients with

echinococcosis depends on early and accurate diagnosis and prompt surgical or

chemotherapeutic treatment. Whilst the problem of diagnosis in many organ

systems has been solved, diagnosis of cerebral echinococcosis still represents

a significant challenge. Frequently cerebral echinococcosis is misdiagnosed for

other conditions such as tumours, abscesses or not parasitic cysts (Kariev et

al 1990, Junarddi et al 1990). Late diagnosis of cerebral echinococcosis often

leads to a poor prognosis. There are frequent complications during Suring to

remove cerebral cysts. Rupture of the cysts can lead to an outpouring of

contents that include germinal elements, pus and necrotic elements, into the

serous cavities of patients. This can lead to serious complications such as

allergic reactions, anaphylactic shock, epileptic attacks, suppuration and

recurrence of disease (Akmatov et al 1994, Akshunbaev et al 2000, Kariev et al

1990, Petrovsky et al 1985, Jimenes-Mejias et al 1991, Kayu et al 1975). In

addition, symptoms may worsen and central nervous system encephalitis may

develop, intravascular coagulation and other problems associated with the disintegration

of the cyst and the leakage of cyst fluid which contains acetic and lactic acid

and other substances, into the blood. Serotonin, prostaglandin and kinins may

be released in response this release of cyst fluid (Ersahim et al 1993). This

can result in cerebral hypostasis and brain swelling (Akhunbaev 1964, Petrovsky

et al 1985, Lunarddi et al 1990). Damage to the ventricular systems can alter

the fluid dynamics in the brain, leading to pressure on aub-arachnoid tissues

and angiospasm.

Epilepsy is a frequent complication of

cerebral echinococcosis as cyst fluid is allergenic and irritant to the brain

tissue and protoscolices are sometimes not completely removed leading to

daughter cysts and relapses.

The underlying reasons for these pathogenic

mechanisms is the space occupying lesion and the leakage of blood and necrotic

or cyst material into the sub-arachnoid space. The important phase of the

treatment with cerebral echinococcosis, after removal of the cysts, is adequate

drainage of nercotic material and blood from the sub-arachnoid spaces. To

remove blood, passive drainage using a polyethylene or rubber tube is required.

However, this drainage requires close supervision as the tubes are frequently

blocked with blood clots or detritus. Even wide bore tubes need constant supervision. A technique for the drainage

of fluid from the brain has been devised. Blood and other detritus are flushed

out of the sub-archnoid spaces by perfusion fluids. However, the technique has

to be undertaken with great care to avoid increasing intracranial pressure or

bleeding.

The purpose of this study was to define the

clinical characteristics of cerebral echinococcosis, the rate of parasite

growth and the topographical relationships with cerebral white and grey matter

and the ventricular system, and then to study the active draining of the

sub-arachnoid spaces following cyst removal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the last 15 years, 105 patients have presented with

cerebral echinococcosis. This represents 0.9 % of

all patients treated with space occupying lesions of the brain.

In a total of 65 patients external drainage from the

cranial cavity was undertaken. In these patients the efficacy was assessed

by changes in intra-cranial pressure and cerebral circulation by

impedance radiography.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initial symptoms often appeared long before

clinical diagnosis. A space occupying lesion was suspected based on evolving central and

peripheral neurological symptoms. In 38 patients, cerebral echinococcosis

was confirmed with the application of computer and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography. In all these patients

neurological symptoms like exophthalmoses, paresis, titanic spasms

of the neck muscles, horizontal nystagmus with rotary components,

and problems of coordination were

marked. In 12 patients the first symptoms observed were clonic epileptiform attacks up to 10 years before diagnosis.

There developed into focal epileptiform attacks and localized

pyramidal symptoms. In 43 patients the first symptoms were

headaches. In 17 of these patients headaches

occurred only a few months before diagnosis although this was many years after the first symptoms (such as epileptiform

seizures). In 9 patients, headache was the presenting clinical

symptom.

Marked eosinophilia was seen in 53 of the

65 patients. Radiological evidence of the development

of cerebal hypertension includes an increase in the size of the

cranium, impressions on the base of the

cranium, funnel finger shaped depression, hypertrophy of ventricular veins and rarefaction of the skull. The radiological

changes depend on the sizes of the hydatid cysts and disease

duration. Intensity of headaches did not correlate with the

hypertensive changes of the cranium.

Congestion

of the ocular fundus

was seen in 63 patients. In 11 of then, these had developed into

secondary atrophy of the optic nerves. Development of this

syndrome is often associated with massive intracranial

pressure and obstruction of drainage from the ventricular and

paraventricular systems by cysts with a volume of

200-250 cm3 The size of cysts from this series of patients varied between 13cm and 12cm in diameter.

Cerebral spinal fluid of 38

patients was normal and in 4 patients there was a moderate increase

in lymphocytes.

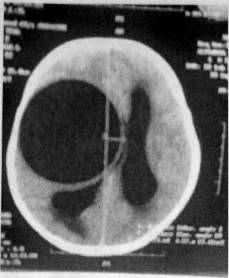

According to the computer and nuclear magnetic

tomography, the cysts are located in the white matter, mainly in the temporal

occipital lobe (Ersahin et al 1993). Of 65 patients presenting with cerebral

echinococcosis, 53 had single cyts, whilst 4 also had pulmaonary cysts and 4

had cyts in multiple locations. Single cysts were seen in the white matter of

the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes and in the ventricular cavity.

Patients with pulmonary cysts had 2*5 cerebral cysts in the white matter on the

convex and basal loves of the brain. The severity of clinical signs was often

not associated with the size but number and location of lesions. We compared

the spontaneous chemiluminescence with composition of the protein in the

cerebral spinal fluid . Weak fluorescence does not depend on (he quantity

but type of protein present. When biological liquids are exposed

to ultraviolet lights reactions of free radicals

can lead to the formation of unidentified fatty acids. Thus the

intensity of photo-induced chemiluminescence depend on processes

at the cellular level and on the level of exposure.(pic I).

In a series od cases of cerebrai echinococcosis and

controls we have investigated the magnitude of chemiluminesce of the CSF.

Comparison of the data suggests that CSF from cases with cerebral echinococcosis

have more intense chemiluminescence than controls; this is an additional

criterion that can be used in assessing a diagnosis.

When there is intracranial haemorrhage good drainage

is required in 3 circumstances. In the first, which was encountered in 14

patients, good perfusion and drainage of the subarachnoid space and areas of

surgical intervention were provided. Such conditions occur 2-3 hours after

surgery. For rapid removal of the intracranial fluid, rapid perfusion is

required with the drainage tube below the head of the patient. If the drainage

tube is blocked, even partially, then there can be an uncontrollable increase

in intracranial pressure with hypertensive syndromes developing.

The second situation arises when the outflow of fluid

is greater then the inflow during perfusion drainage caused by the siphon, and

thus creating negative intracranial pressure. This negative intracranial

pressure can lead to haemorrhage. In 29 patients full haemostasis had been

achieved within 30-60 minutes postoperatively as shown by the absence of blood

from the perfusion tubes. The perfusion flow was decreased but in a number of

patients haemorrhage commenced again within 20 minutes. This was controlled in

12 patients by increasing the perfusion rate again and adjusting the pressure

of the drainage fluid. In 7 patients, haemostatic medical therapy was required.

In 2 patients the surgical site was reopened and haemotoma was removed.

In the third situation complete or partial blockage of

the drainage tubes by blood clots or brain detritus can lead to a rapid

increase in intracranial pressure. Increase in intcacranial pressure was

observed in 22 patients who clinically presented with intense headache, nausea,

vomiting, shivering, psychomotor anxiety and excitation. Loss of consciousness,

tachypnoea and tachycardia occurred in 5 patients. After emergency intervention

to remove the excess fluid, the patients rapidly relopsed in to normaky.

Usually, even in the presence of such adverse

pathological problems, providing adequate drainage is provided for 2 days, few

long-term effects are witnessed in the majority of patients.

During non-con trolled perfusion drainage

under negative intracranial pressure, fluctuations of the venous tension are

not seen. Pulsatory and respiratory fluctuations on plethysmogram curves are

not defined.

Only aperiodic changes in pressure are

reflected by the bodily position. Gradual increases in intracranial

pressure begin some 5-6 hours after surgery with an increase in the amplitudes

of pressure changes.(pic 2).

|

Pic 2. |

The long-tern follow-up of patients, who were given active intracranial perfusion, were investigated. In the first two groups, there were no relapses; in the third were 2 relapses out of 22 of interventions.

Good drainage of the intracranial cavity

after sugery provides optimum conditions for the removal of debris (such as from the cyst), blood and

necrotic material. This permits the establishment of normal intracranial

pressure, blood circulation and brain metabolism. The condition of the patient

improves, consciousness is restored, and clinical symptomatology decreases.

Meningeal and fever responses do not develop, or only moderately, and then

disappear within 2 days. There are decreased signs of thirst, headache,

vomiting, psychomotor anxiety and excitement. Blood pressure is stabilized and

respiratory and pulse rates return to normal.

Thus, adjustable perfusion-drainage of the

cranial cavity is an important and effective postoperative treatment for

cerebral echinococcosis. The patients condition is improved in the postoperative

period and the time spent in hospital is reduced.

CONCLUSION

Based on our surgical experience, and

others reported in the literature, the important features in die diagnosis and

management of cerebral echinococcosis include: 1 )a history of episodic pyrexia

of unknown origin 2)the presence of shot-term serous meningitis and epileptic

attacks 3)slowly progressing focal neurological disease discrepancies between

changes in the radiological appearance of bones of the cranium and duration of

clinical neurological signs 5)data from computer tomography and magnetic

resonance imaging in defining the number, size and location of cerebral cysts

and any pathological changes in surrounding cerebral tissue 6)chemiluminescence

of CSF 7)adjustablc perfusion drainage of the cranial cavity following removal

of the cyst enables supervision of intracranial pressure during the post

operative period 8)flushing out of protoscolices as a result of cyst rupture

reduces the rick of recurrence.

References

1.

AKMATOV В A (1994) Echinococcosis. Bishkek,

pp 6-131

2.

AKSHULAKOV

SK, HACHATRYN VA&MAKHAMBETOV ET (2000) Echinococcosis of the central

nervous system. Almaty, 23 pp.

3.

AKHUNBAEV IK

(1964) Echinococcosis. Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 35, 885-895. CATALTEPE et al

(1992) Intracranial hydatid cysts: experience with surgical treatment of 120

patients.

4.

Neurochirurgia

35, 108-111.

5.

ERSAHIN Y, MULTLER & CUZELBAB (1993) Intracranial

hydatid cysts in children. Neurosurgery 332, 219-224/

6.

MENES-MELAS ME et al (1991) Hidatidosis cerebral. Med

Clin (Barcelona) 97,125-132. KFR1EV MN, AZAROVA TG, MALAMUT et al (1990) Actual

questions of alveococcosis. Tashkent pp 84-85.

7.

KAY A U et al (1975) Intracranial hydatid cysts. Study

of 17 cases. Journal of Neurosurgery 42, 580-584.

8.

KORNYASKY GP, BASIN & EPSHTEIN IV (1968) Parasitic

diseases of the central nervous system. Moscow, pp 79-139.

9.

LUNARDDI P et al (1990) Cerebral hydatidosis in

childhood. Neurosurgery 36, 312-314/ PETROVSKY BV, MILONOV OB & DESNICHIN P

(1985). Surgery of echinococcisis . Moscow.

10.

ROSIN VS (1991) Diagnosis of cystic echinococcisis of

the brain. Contemporary Medicine 2, 84-86.