Tåõíè÷åñêèå íàóêè/ Àâèàöèÿ è êîñìîíàâòèêà

Nickolay Zosimovych1, Anatoly Voytsytskyy2

1Tecnólogico

de Monterrey (Campus Gualajara, Mexico)

2Zhytomyr National

Agrarian and Ecological University (Zhytomyr, Ukraine)

DISTURBED MOTION OF THE LAUNCH VEHICLE WITH

INTEGRATED GPS/INS NAVIGATION SYSTEMS

In these article has been conducted a presimulation analysis

of disturbed motion of the launch vehicle with integrated GPS/INS navigation

systems. It was determined the main characteristics describing the internal structure of vehicle.

Key

words: Integrated GPS/INS

navigation systems, gimbaled inertial navigation system (GINS),

GPS receiver, launch vehicle, mathematical model (MM), thrust,

propulsion, deviation.

Introduction. A key tendency in the development of

affordable modern navigation systems is

displayed by the use of integrated GPS/INS navigation systems consisting of a gimbaled inertial navigation system (GINS) and a multichannel GPS receiver [1]. The investigations show [2, 3], that such systems of navigation

sensors with their relatively low

cost are able to provide the required accuracy of navigation for a wide class of

highly maneuverable objects, such as airplanes,

helicopters, airborne precision-guided weapons,

spacecraft, launch vehicles and recoverable orbital carriers.

Let us briefly examine the scientific and

technical problems arising when making the corresponding models

and algorithms.

MM of spatial motion of center of

mass and relative to center of

mass of a solid launch vehicle is

well known and widely described

in sources. The greatest difficulty in the implementation of such a model as a part of the model of

the environment, represents a model of a solid-propellant rocket engine with thrust distribution in

respect to the nominal model in

mind and the model of stage separation

from the point of view of the influence

of disturbing moments that arise when dividing into initial conditions of the motion of the next stage.

Task Statement. Let's consider the above objectives,

having regard to peculiarities of the subject of inquiry, namely a commercial

launch vehicle, designed to launch payloads into

low Earth orbit (LEO) or geostationary orbit

(GSO), in more details.

Fig. 1. Launch vehicle Vega (Vettore

Europeo di Generazione Avanzata, ASI&ESA) [4]

Within the framework

of this study we shall consider a light launch vehicle which has been jointly

developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency (ASI)

since 1998 (Fig.1). It is qualified to launch

satellites ranging from 300 kg to 2000 kg into low circular polar orbits. As a rule,

these are low cost projects conducted by research organizations and universities

monitoring the Earth in scientific missions as well as spy satellites,

scientific and amateur satellites. The

launch vehicle Vega [4] is the prototype of the vehicle under development.

The planned payload to

be delivered by the launch vehicle to a polar orbit at an altitude of ~700 km

shall be 1500 kg. The launch vehicle is

tailored for missions to low Earth and Sun-synchronous orbits. During the first

mission the light class launch vehicle is to launch the main payload, a

satellite weighing 400 kg, to an altitude of 1450 km with an inclination of the

orbit 71.500. Unlike most single-body launchers, this vehicle is to

launch several spacecraft.

In order

to make a model for disturbed motion of the above mathematical model shall be supplemented with

mathematical models of the following

disturbing factors:

· thrust

distribution in the propulsion system in respect to nominal thrust profile;

· manufacturing defects of structure and assembly

components;

· variations of atmospheric parameters and wind fields.

Let's cconsider a model of each of these factors

in detail.

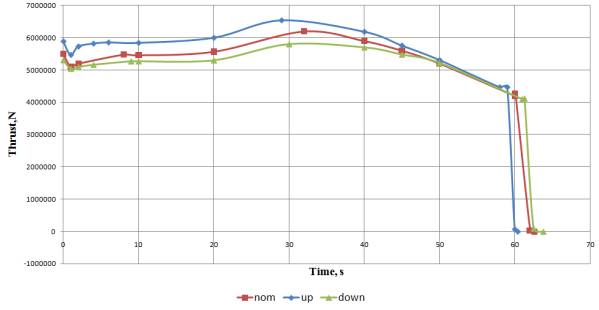

A model of thrust distribution in the propulsion system. As mentioned above, nominal

profiles of thrust in vacuum and the nominal mass flow rate of the propellant specified in a table are used when

calculating a thrust. In addition to the nominal profile of

thrust and propellant mass flow the performance

of propulsion system accompanies the

product with profiles of the

so-called "upper" and

"lower" thrust with relevant profiles of

propellant mass flow and of the center of gravity

of the fuel solid-block (Fig.2).

Fig. 2.

Profiles of propellant mass flow

These profiles characterize variation of

the burning rate of the

fuel solid-block depending on the specific chemical composition of the propellant, atmospheric

conditions, location of the fuel solid-block inside the

propulsion system, etc.

In order to make

a model of thrust distribution we may apply deterministic,

stochastic and minimax approaches. Proceeding from the physical aspect of the factor discussed we applied the

stochastic approach in this paper [5] based on the following.

The distribution

of thrust was considered as a uniformly distributed random variable in the range ![]() with -1 corresponding to the

"lower" thrust, 0 being

the nominal profile and +1 being the "upper"

thrust. This random

variable is implemented for each

engine of the launch vehicle only one time before the simulation hereafter the profile of real thrust

as well as of mass consumption and

of the center of the fuel solid-block shall be constructed

based on the Chebyshev polynomials approximation and used similarly as in the calculation of traction, weight and

control moments of the launch vehicle.

with -1 corresponding to the

"lower" thrust, 0 being

the nominal profile and +1 being the "upper"

thrust. This random

variable is implemented for each

engine of the launch vehicle only one time before the simulation hereafter the profile of real thrust

as well as of mass consumption and

of the center of the fuel solid-block shall be constructed

based on the Chebyshev polynomials approximation and used similarly as in the calculation of traction, weight and

control moments of the launch vehicle.

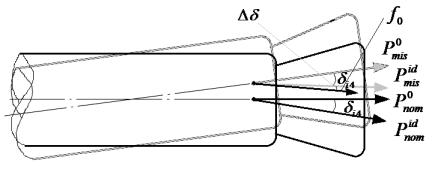

Fig. 3. Engine deviations and

deflection angles of the nozzles

in development tests (failure tests) of control inputs: ![]() is a sum of

forces acting upon the launch vehicle;

is a sum of

forces acting upon the launch vehicle; ![]() is an ideal

nominal thrust of the propulsion system;

is an ideal

nominal thrust of the propulsion system; ![]() is nominal thrust of the propulsion system in vacuum

environment;

is nominal thrust of the propulsion system in vacuum

environment; ![]() is a

«disturbed» ideal thrust;

is a

«disturbed» ideal thrust; ![]() is «disturbed»

thrust in vacuum environment;

is «disturbed»

thrust in vacuum environment; ![]() is engine

«deviation» of the launch vehicle;

is engine

«deviation» of the launch vehicle; ![]() is deflection

angle of the nozzles consequent on

testing and correction of control signals

is deflection

angle of the nozzles consequent on

testing and correction of control signals

The line of thrust

shall be determined in the body-fixed frame and depend on the orientation of

the longitudinal axis of the nozzle relative to the longitudinal axis of the

launcher engine. When considering the undisturbed motion of the launch vehicle,

engine angles shall be regarded as nominal and the direction is determined only

by the deflection angles of the nozzles consequent on testing and correction of

control signals (Fig. 3). When considering the disturbed motion of the launch

vehicle, the line of thrust shall be determined on account of errors in the

assembly of the launch vehicle, engine deviations and errors in testing and

correction of controlling influence. Let's consider errors in the assembly of

the launch vehicle and engine deviations closer.

Manufacture defects of structure

and assembly components of the launch vehicle. As

already mentioned, when considering the undisturbed motion the launch vehicle

shall be considered as ideally assembled, i.e. axes of

the structure members coinñide, there is

no displacement between the

members, etc. In a real situation assembly errors are inevitable along reasonable length of the launch

vehicle which leads to a change in the

moments of inertia of the launch vehicle, the center of mass,

and most importantly, a change in the

thrust line.

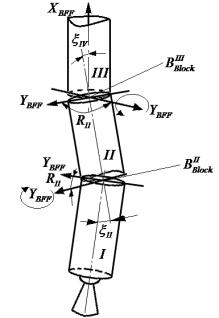

To describe this

disturbing factor let's consider the launch vehicle as a combination of

components that make it up (a nose cone, a satellite with a bus, the fourth

stage engine pack, a control bay, the third stage block, the second stage block, the first stage boosters) [5]. Each of these

components has its mass and inertial characteristics (depending on

the change in its mass. The moment of inertia, the center of block mass are set

by designers of the launch vehicle) in an ideally bound coordinate system.

In addition, each

component is characterized by the coordinates of points of its anchorage with

the adjacent components and assembly errors, given in the form of the tilt

-related coordinate system relative to the adjacent structural component [5].

This error is considered normally expected corresponding to the nominal

arrangement of components and variance set by designers of the launch vehicle

[6] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Errors

in the assembly of![]() stages in a bound

coordinate system

stages in a bound

coordinate system

So, for example, errors in the assembly of the

third stage block relative the

control unit are characterized by incidental orientation angles.

![]()

Usually assembly begins with the control unit because it includes a measuring

unit and a gyroplatform implementing inertial reference frame and measuring the

orientation angles of the launch vehicle [5]. Further units shall be docked up and down the

launch vehicle subject to specific error

values in the assembly of the

launch vehicle. Thus, the center of mass

and moments of inertia shall be

recalculated in the bound reference frame. Besides,

there shall be calculated deflection angles of the nozzles of the launch vehicle and arms of thrust forces required in the calculation of moments.

A model of variations of atmospheric parameters and wind fields. As is known, the

aerodynamic forces acting on the launch vehicle are in particular dependent on

the atmospheric parameters (density, pressure, temperature). These parameters,

in their turn, depend on the altitude and geographic latitude, time and season,

the parameters of solar activity and other factors.

To calculate

trajectories and conduct other studies we should use standard atmosphere (SA)

tables while designing a launch vehicle. They give some average parameters for

tranquil atmosphere depending on the height [6-8]. Deviations of

the atmospheric parameters from the standard values, as well as wind are

atmospheric disturbances which are taken into consideration when one studies

the disturbed motion of the launch vehicle.

To solve the problems of

flight dynamics, we also need to know the range of possible deviations of these

parameters corresponding to a certain level of probability in addition to

standard values of atmospheric parameters both excluding seasons

and locations on the globe, and taking them into account. In addition, more

accurate research requires knowledge of the statistical relationships between

the random deviations of each parameter at different heights, etc.

There are various

methods describing disturbance of atmospheric parameters. In the present paper,

we shall use the canonical expansion method for random components of

atmospheric parameters [9]. The substance of the method is as follows. The

temperature ![]() and the density of the atmosphere

and the density of the atmosphere ![]() can be represented in the following way [10]:

can be represented in the following way [10]:

![]()

where ![]() are standard

values of the temperature and the density ;

are standard

values of the temperature and the density ;

![]() is deviation

from the standard temperature;

is deviation

from the standard temperature;

![]() is a relative

deviation from the standard air density.

is a relative

deviation from the standard air density.

In order to set

random functions ![]() and

and ![]() we shall use

the canonical expansion method [11].

we shall use

the canonical expansion method [11].

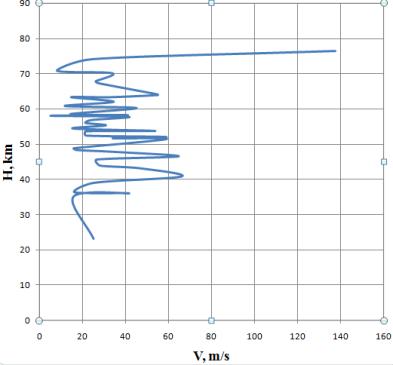

Fig. 5. Mean values of the zonal wind component in Guam (processing of the results by the author based upon the data obtained by 9 meteorological rockets during the period between 3rd and 25th September, 1958) [12]

With reference to the case under consideration, the atmospheric

parameters as random functions of

height of a point above the

Earth's surface are represented as canonical expansion as follows:

![]()

where ![]()

![]() are mean deviations from the values of standard atmosphere corresponding to the point in question;

are mean deviations from the values of standard atmosphere corresponding to the point in question;

![]()

![]() are some nonrandom deviation from the mean deviations

are some nonrandom deviation from the mean deviations ![]() and

and ![]()

Wind effect is taken into account in changing airspeed vector. Thus,

taking into account the effects of wind

air vector shall be written as:

![]()

where ![]() is an air vector

in undisturbed motion;

is an air vector

in undisturbed motion; ![]() is a gust velocity vector.

is a gust velocity vector.

Wind shall be considered horizontal, i.e. without vertical movement of air masses,

and the absolute velocity depends on the altitude and geographical

coordinates of the point, and the direction is characterized by azimuth angle - i.e. wind direction relative

to the north.

The absolute

value of the wind speed is

determined by approximating of

the profiles of wind velocity that

are set apriori (Fig. 5), and the azimuth angle is

a random variable normally distributed with mean corresponding to the nominal direction of the wind variance given by the

Customer:

![]()

CONCLUSIONS

1. Based on the above, we have set a technical problem of the conceptual

design of an integrated navigation system for the space launch vehicle qualified to inject small artificial Earth satellites into low and medium circular orbits.

2. We have made an analysis of possible models of flight and navigation measurements and identified

key potential difficulties in the process of their creation.

References

1.

Zosimovych Nickolay. Integrated Navigation System for Prompting of the

Commersial Carrier Rocket. Information technology Conference for Academia and

Professionals (ITC-AP 2013), Sharda University, India, 19-21 April, 2013.

2.

Flight instruments and navigation systems.

Politecnico di Milano - Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aerospaziale, Aircraft

systems (lecture notes), version 2004.

3. George M. Siouris.

Aerospace Avionics Systems. Academic Press, INC 1993.

4.

http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/ - Âåãà

(ðàêåòà-íîñèòåëü).

5. Veniamin V. Malyshev, Michail N. Krasilshikov, Vladimir T. Bobronnikov,

Victor D. Dishel. Aerospace vehicle control, Moscow, 1996.

6. Furman T.T. Approximate Methods in Engineering Design, Vol. 155:

Mathematics in Science and Engineering, Edited by Richard Bellman, 1981.

7. CIRA 1972 (COSPAR International Reference Atmosphere 1972), Berlin,

1972.

8. ÃÎÑÒ 4401-64. Òàáëèöû

ñòàíäàðòíîé àòìîñôåðû. Èçä-âî ñòàíäàðòîâ, Ìîñêâà, 1964.

9. Carlo L. Botasso. Solution Procedures for Maneuvering Multibody Dynamics

Problems for Vehicle Models of Varying Complexity. Multibody Dynamics,

Computational Methods in Applied Sciences, Vol. 12, pp.57-79, 2008.

10. Steven A. Hildereth, Carl Ek. Long-Range Ballistic Missile Defence in

Europe. Congressional Research Service, RL34051, January 21, 2009.

11. Albertos P., and Sala A. Multivariable Control Systems, Valensia, Spain,

2004.

12. Ìàòâååâ Ë.Ò. Îñíîâû îáùåé

ìåòåîðîëîãèè. Ôèçèêà àòìîñôåðû. Ë.: Ãèäðîìåòåîèçäàò, 1965, 867 ñ.