VI²I Ìåæäóíàðîäíàÿ íàó÷íî-ïðàêòè÷åñêàÿ êîíôåðåíöèÿ

«Íàó÷íàÿ ìûñëü èíôîðìàöèîííîãî

âåêà – 2012»

Ýêîíîìè÷åñêèå íàóêè/ 2.Âíåøíåýêîíîìè÷åñêàÿ

äåÿòåëüíîñòü.

Dinara Aitkazy

student of

Master EUCAIS program

Free

trade: the arguments pro and cons

Free trade is a system of international trade policy, which allows traders to act without

interference from government. Under a free trade policy, prices are a

reflection of true supply and demand, and are the sole determinant

of resource

allocation.

Several different models have

been proposed to predict patterns of trade. One of the first adherents of free

trade was famous David

Ricardo (1772-1823). David

Ricardo made a case

for free trade by presenting a specialized economic proof featuring a single

factor of production with constant productivity of labor in two goods, but with

relative productivity between the goods different across two countries.

Ricardo's model demonstrated the benefits of trading via specialization—states

could acquire more than their labor alone would permit them to produce. This

basic model ultimately led to the formation of one of the fundamental laws of

economics: The Law of Comparative

Advantage [1].

The Law states that each member in a group of trading partners should

specialize in and produce the goods in which they possess lowest opportunity costs relative to other

trading partners. In other words, countries specialize in producing what they

produce best instead of producing a broad array of goods. According to the law

of comparative advantage the policy permits trading partners mutual gains from trade of goods and

services. This specialization permits trading partners to then exchange their

goods produced as a function of specialization. Under a policy of free trade,

trade via specialization maximizes labor, wealth and quantity of produced goods,

exceeding what an equal number of autarkic states could produce.

Eli

Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin produced as an alternative to the Ricardian

model Heckscher-Ohlin model.

This theory stresses that countries should produce and export goods that

require resources (factors) that are abundant and import goods that require

resources in short supply. This theory differs from the theories of comparative

advantage since this theory focused on the productivity of the production

process for a particular good. On the contrary, the Heckscher-Ohlin theory

states that a country should specialize production and export using the factors

that are most abundant, and thus the cheapest. Not to produce, as earlier

theories stated, the goods it produces most efficiently.

The theory argues that the pattern of international trade is determined

by differences in factor endowments. It predicts that

countries will export those goods that make

intensive use of locally abundant factors and will import goods that make

intensive use of factors that are locally scarce. In an idealized model

international trade would actually lead to equalization of the prices of

factors such as labor and capital between countries. In reality, compete

factor-price equalization is not observed because of wide differences in

resources, barriers to trade, and international differences in technology.

Despite the model greater complexity it did not prove much more accurate

in its predictions. However, from a theoretical point of view it did provide an

elegant solution by incorporating the neoclassical price mechanism into

international trade theory.

Free trade is composed of the following features:

§ trade of goods and services without taxes (inc. tariffs) or other trade barriers (e.g., quotas on

imports or subsidies for producers);

§ the absence of

"trade-distorting" policies (such as taxes, subsidies, regulations, or laws) that give some firms, households, or factors

of production an advantage over others;

§ free access to markets;

§ inability of firms to distort

markets through government-imposed monopoly or oligopoly power;

§ free movement of labor between and within countries;

§ free movement of capital between and within countries.

What arguments are there in favor of free trade?

There

is no country in the world approached to completely free trade. The city of

Hong Kong (which is legally part of China but has a separate economic policy) may

be the only modern economy with no tariffs or import quotas, but is expected to

lose this feature once integrated into mainland economy. As we see theoretical

models suggest that free trade will avoid the efficiency losses associated with

protection. Many economists believe that free trade produces additional gains beyond

the elimination of production and consumption distortions. Moreover, even among

the economists who believe free trade is a less than perfect policy, many

believe free trade is usually better than any other policy a government is

likely to follow [2].

The arguments in favor of

free trade are as following:

First

fundamental reason is efficiency of free trade. As we know, trade potentially

benefits a country through expansion economy’s choices, which means that it is

always possible to redistribute income in such a way that everyone gains from

trade.

The idea that everyone could gain from trade unfortunatly does not mean that everyone

actually does. The presence of loosers as well as winners from trade is one of

the most important reasons why trade is not free [3].

One of the ways to understand the potential benefits of free trade is through

analyzing the impact of a tariff or import quota.

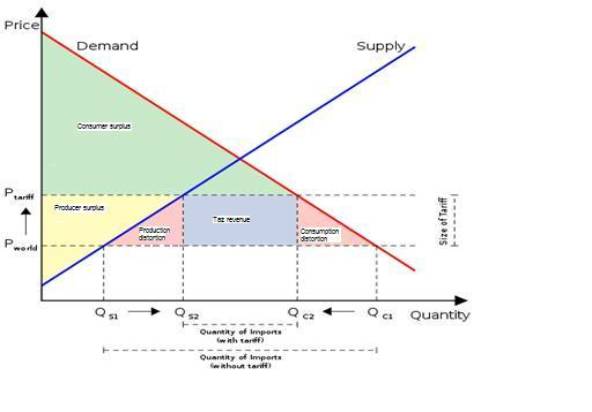

Figure 1. The efficiency case for free trade Source: Krugman, Obsfeld, 2009, p.

214.

Source: Krugman, Obsfeld, 2009, p.

214.

According to P. Krugman and M. Obsfeld [4], the efficiency case for free

trade is simply the reverse of the cost-benefit analysis of a tariff. Figure 1

shows the case of a small country which cannot influence foreign export prices.

As shown on the figure above, the effect of the

imposition of an import tariff on some imaginary good increases

the domestic price from Pworld to Ptariff. The higher

price causes domestic production to increase from QS1 to QS2

and causes domestic consumption to decline from QC1 to QC2.

At the same time, the pink triangles are the net loss to the economy caused by

the existence of the tariff and it does so by distorting the economic

incentives of producers and consumers.

This has three main effects on national welfare:

·

Consumers are made worse off because the consumer surplus (green region)

becomes smaller.

·

Producers are better off because the producer surplus (yellow region) is

made larger.

·

The government also has additional tax revenue (blue region).

However,

the loss to consumers is greater than the gains by producers and the

government. But by having free trade (and removing the tariffs) would be a net

gain for society.

Recent estimates show the gains from a move to worldwide free trade,

measured as a percentage of GDP. However for advanced economics the gains from

free trade are somewhat smaller (0.57% of GDP for US, 0.61% of GDP for EU and

0.85% of GDP for Japan), while for poorer “developing countries” (including Kazakhstan

and other Central Asian countries) the

gains are somewhat larger (1.4% of GDP of developing countries) [5].

An almost identical analysis of this tariff from the

perspective of a net producing country yields parallel results. From that

country's perspective, the tariff leaves producers worse off and consumers

better off, but the net loss to producers is larger than the benefit to consumers

(there is no tax revenue in this case because the country being analyzed is not

collecting the tariff). Under similar analysis, export tariffs, import quotas,

and export quotas all yield nearly identical results. Sometimes consumers are

better off and producers worse off, and sometimes consumers are worse off and

producers are better off, but the imposition of trade restrictions causes a net

loss to society because the losses from trade restrictions are larger than the

gains (on the graph in this case distortions areas reflect the societal loss).

Free trade creates winners and losers, but theory and empirical evidence show

that the sizes of the winnings from free trade are larger than the losses [6].

Second

argument in favor of free trade is a dynamic gain from free trade. There is a

widespread belief among that calculations, even though they report substantial gains

from free trade in some cases, do not represent the whole story. In small

countries in general and developing countries in particular, many economists

would argue that there are important gains from free trade not accounted for in

conventional cost-benefit analysis [7].

One of

them involves economies of scale. Protected markets not only fragment

production internationally, but by reducing competition and raising profits,

they also led too many firms to enter the protected industry. With a

proliferation of firms in narrow domestic markets, the scale of production of

each firm becomes inefficient.

Third argument

for free trade is that by providing entrepreneurs with an incentive to seek new

ways to export or compete with imports, free trade offers more opportunities

for learning and innovation than are provided by a system of “managed” trade,

where the government largely dictates the pattern of imports and exports. According

to the P. Krugman

and M. Obsfeld [8] the experiences of

less-developed countries that discover unexpected export opportunities when

they shifted from system of import quotas and tariffs to more open trade

policies.

Fourth is political

arguments reflects the fact that a political commitment to free trade may be a

good idea in practice even though there may be better policies in principle.

Economists often argue that trade policies in practice are dominated by special

–interest politics rather than consideration of national costs and benefits.

Economists can sometimes show that in theory a selective set of tariffs and

export subsidies could increase national welfare, but in reality any government

agency attempting to pursue a sophisticated program of intervention in trade

would probably be captured by interest groups and converted into a device for redistributing

income to politically influential sectors. If this argument is correct, it may

be better to advocate free trade without exceptions, even though in purely

economic grounds free trade may not always be the best conceivable policy [9].

Another political reason as a function of

economic interdependence can be the

prediction that states who share strong mutually-beneficial trading

relationships will be far less likely to start a war with one another.

Fifth argument in favor

of free trade is negotiations for tariff reductions (Free trade agreements). It

is economically efficient for a good to be produced by the country which is the

lowest cost producer, but this will not always take place if a high cost

producer has a free trade agreement while the low cost producer faces a high

tariff. Applying free trade to the high cost producer (and not the low cost

producer as well) can lead to trade diversion and a net economic loss [10].

What arguments are there to support the contrary?

As I mentioned before, free trade differs from other

forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading

countries are determined by artificial prices that may or may not reflect the

true nature of supply and demand. These artificial prices are the result of protectionist trade policies, whereby

governments intervene in the market through price adjustments and supply

restrictions. Such government interventions can increase as well as decrease

the cost of goods and services to both consumers and producers.

Protectionism

– is the economic policy contrary to free trade policy

which directed to:

§ prevent foreign

take-over of domestic markets and companies;

§ protection from

foreign competition in strategic important industries of the national economy;

§ temporary

protection of the newly established branches of the national economy;

§

broadening foreign markets.

Protectionism is a policy

where the government restricts trade with other countries through a series of

measures:

1. tariffs – taxes on imported goods. They make foreign products more

expensive than similar domestic, thus, increase competitiveness of the domestic

product.

2. quotas – restrictions on the number of imported goods of a certain

name and type.

3. export subsidies – payments, allowing domestic producers to sell their products abroad at lower

(so-called dumping) prices.

The arguments to support the

contrary of free trade are as following:

First argument is a protection of industries related to

national defense. If in those industries would dominate foreign competitors,

then these industries may find themselves in a difficult position in war

situation.

Second is infant industry argument - many countries use

protectionist barriers to protect their still underdeveloped industries. Protectionists

believe that infant industries

must be protected in order to allow them to grow to a point where they can

fairly compete with the larger mature industries established in foreign

countries. Otherwise, they will die before they reach a size and age where economies of scale,

industrial infrastructure, and skill in manufacturing will be progressed enough

to allow the industry to compete in the global market.

Third argument is a protection of the more developed

countries from competition of cheaper foreign labor. Since free trade promotes

equal access to domestic resources (including human) for domestic and foreign

participants as well. Visa entrance policies tend to discourage free

reallocation between many countries, and encourage it with others. High freedom

and mobility has been shown to lead to far greater development than aid

programs in many cases, for example eastern European countries in the European

Union. In other words visa entrance requirements are a form of local

protectionism.

Fourth is that countries can improve their terms of trade

through optimal tariffs and export taxes. This argument is not too important in

practice, however. Small countries cannot have much influence on their import

or export prices, so they cannot use tariffs or other policies to raise their

terms of trade. On the other hand, large countries can influence their terms of trade, but in imposing tariffs they

run the risk of disrupting trade agreements and provoking retaliation [11].

Fifth argument rests on domestic market failures. If

some domestic market, such as labor market, fails to function properly,

deviating from free trade can sometimes help reduce the consequences of this

malfunctioning. The theory of the second best choice that if one market fails

to work properly it is no longer optimal for government to abstain from

intervention in other markets. A tariff may raise welfare if there is a

marginal social benefit to production of a good that I not captured by producer

surplus measures [12].

It is worth noting that free trade is often opposed by

domestic industries that would have their profits and market share reduced by

lower prices for imported goods [13]. For example, if a country will reduce

tariffs on imported sugar, sugar producers would receive lower prices and

profits, while sugar consumers would spend less for the same amount of sugar

because of those same lower prices. The economic theory of David Ricardo holds

that consumers would necessarily gain more than producers would lose [14]. Since

each of domestic sugar producers would lose a lot while each of a great number

of consumers would gain only a little, domestic producers are more likely to

mobilize against the lifting of tariffs [15]. More generally, producers often

favor domestic subsidies and tariffs on imports in their home countries, while

objecting to subsidies and tariffs in their export markets.

Even

though inadequacy of most of the arguments in favor of protectionism is proved

both in theory and in practice, some degree of Protectionism is nevertheless the norm

throughout the world.

My own view on the benefits of free trade, example Kazakhstan and its trade

partners.

Kazakhstan: attempt to combine pros of the trade and protectionism

through regional integration.

Kazakhstan is a member of several regional integration

processes. Most important of which are the Eurasian Economic Community

(EurAsEC), Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Common Security Treaty

Organisation (CSTO) and the Customs Union (CU) of Russia, Kazakhstan and

Belarus. The CU is announced to be a first step towards creation of the Single Economic

Area (SEA) in 2012. The three countries constitute the integration core of the

post-Soviet space according to the comprehensive System of Indicators of

Eurasian Integration, of the Eurasian Development Bank [16].

Kazakhstan is a country with highly-opened economy

with foreign trade amount equaling its GDP. Though the country is more

integrated on the global scale rather than regional, it is developing its ties

with neighboring countries through both developing its comparative advantages

and establishing closer bilateral and multilateral connections.

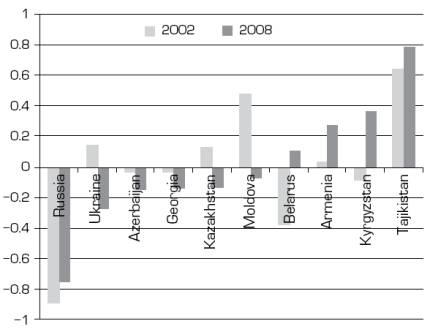

Figure 2. Consolidated indices

of integration of FSU countries (2002 vs 2008)

Source: Vinokurov, Libman 2010, p. 142.

Figure above shows the consolidated indices of

integration of individual countries with CIS- countries. The indices are

calculated for 2008 and 2002, for ten post-Soviet countries (Uzbekistan and

Turkmenistan were excluded due to a lack of data). Higher value of the index

corresponds to higher level of integration. The values vary within a range of

–1 to 1. The scale is calibrated so that the mean value corresponds to zero:

accordingly, countries with a low level of integration have negative indices

and highly integrated countries have positive indices. As we see, Kazakhstan

within the period turned from positive to negative, which means lower

integration level within CIS region. However this is attributed to the fact

that Kazakhstan is considered to be a large economy with a diverse structure of

foreign trade, in which economic ties with the post-Soviet space tend to become

less important. This trend is in line with other fairly rich and large

countries (Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Russia, whereas Georgia’s trend

is mostly driven by political reasons). Within the group only Kazakhstan and

Russia play active roles in formal integration initiatives.

Table 1. The

dynamics of integration of markets in the FSU

Source: Vinokurov, Libman

2010, p. 141-150.

Source: Vinokurov, Libman

2010, p. 141-150.

As shown in the table Kazakhstan has the highest level

of integration in the two country comparison for such sectors as labor

migration (with Kyrgyz) and agriculture (with Azerbaijan). Moreover Kazakhstan

shows high dynamics in developing trade ties (with Ukraine), labor migration

(with Kyrgyz) and agriculture (with Turkmenistan).

Kazakhstan is reported to be a leader in agriculture

integration (based on data on cross-border trade in cereals) in the post-Soviet

space. The country is present in all three leading country pairs:

Kazakhstan-Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan. In

this case, integration of neighboring Central Asian and Caspian states is

presumably based on the export of cereals from Kazakhstan. This is the example

of the comparative advantage theory

working on practice on the regional level.

Customs Union

The most important development within the Former

Soviet Union (FSU) region is undoubtedly, the formation and launch of the

Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia. The Customs Union started

operating on January 1, 2010. A unified Customs Code of the Customs Union was

put in force starting July 1, 2010. Thus with the single tariff in effect and a

single territory “inspections and duty free” mode in force, the operation of

the Customs Union has started. It was declared that all procedures necessary

for shaping the single customs territory will be completed by summer 2011.

The creation of the CU is expected to promote free

trade within the region. Due to the Customs Union, the average non-weighted

customs tariff will increase by 3.9 percentage points, weighted by countries,

the tariff increases by 1.2 percentage points. The average customs rate is

expected to decrease for some goods where the share of Russia in imports is

high [17].

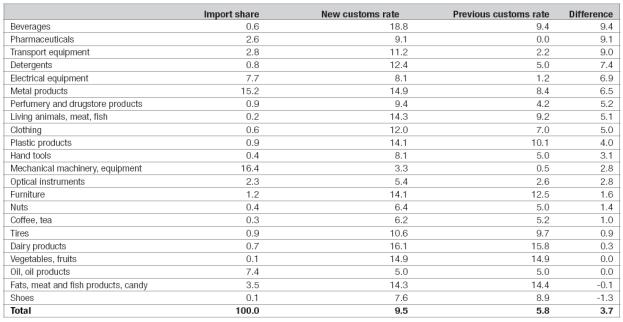

Figure 3. Expected changes in the customs tariffs for

CU-member countries

Source: Holzacker H. (2010) Presentation given on 25

January 2010 in Brussels ‘Custom Union: no big inflation shock, but efforts

needed to offset impact on non-resources sectors’ An analysis by ATF Bank Research. Available at official web-site of

the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia: http://tsouz.ru/news/Documents/Custom_Union

_Glaziev1.pdf (accessed

26 November 2010).

From the figure above we see that almost half of the

tariffs in Kazakhstan will see a reduction due to CU regulation. This is the

lowest proportion compared with Russia (reduction for 82% of the tariffs) and

Belarus (75%). However around 10% of the tariffs in Kazakhstan will increase on

the back of the tariff unification requirement.

The most notable increase in tariffs takes place for

the next goods:

§

group for means of transport (including vehicles)

§

wood

§

refrigerating equipment

§

pharmaceutical preparations

§

electro-mechanical domestic appliances

§

footwear and the articles of apparel

The decrease in tariffs is attributable to the next

products:

·

several agricultural products

·

hides and skins

·

optical medical or surgical instruments and appliances [18].

Table below shows that though the increase in the tariffs

is declared for 10% of the tariffs the amount of the increase is expected to be

considerable. For a large number of items, rates were hiked more than twofold

(medicines, beverages, perfume, clothes). Additionally, under the new customs

regime rates of 75-100% re-appeared, whereas in recent years Kazakhstan’s

maximum rate was 30%. The number of combined percentage and flat fee tariffs

(for example for cars 30%, but not less than 1.45 euros per cubic cm of the

engine) has increased considerably. Previously such duties were applied to

about 1,500 items, now to about 2,000. Combined customs duties serve, first of

all, for the protection of the domestic market from very cheap (most commonly

low-quality) goods and against false declaration of the customs value.

Table 2. Average customs rates

in Kazakhstan for some commodity groups, %

Source: Holzacker

H. (2010) ‘Custom Union: no big inflation shock, but efforts needed to offset

impact on non-resources sectors’ An

analysis by ATF Bank Research. Available at: www.atfbank.kz (accessed 26 November 2010)

The CU is still in the process of fine tuning. On

October 27, 2009 the customs services of the three countries coordinated the

terms of transfer to the unified procedures within the framework of the Customs

Union. A single customs tariff was established and sent to all participants of

the foreign economic activity for examination. It was estimated that the

overall import tariff will rise slightly for Belarus and Kazakhstan and

decrease for Russia by an average of 1%.

However, there are still significant challenges in the

way of establishing the Customs Union. Firstly, it was not easy for the parties

to agree upon one of the key issues – a mechanism of administering the customs

payments and their distribution among the budgets of member states.

Another issue is the uniting of the customs services

of the three states. The process is still at the stage of adjustment,

unification and a more detailed study of the customs procedures. The major

complications are connected with the diversity of the regulatory frameworks of

each of the countries. Currently the member states need to adjust the basic

customs procedures, such as advanced notice and electronic customs entry form,

as well as uniting the procedures of customs clearance.

As of Fall 2010, a number of important issues are

showing their first results, including the procedure of distributing customs

duty revenue among the member countries, and adjustment of the Single Customs

Tariff rates. Importers are reporting the first problems they have begun to

encounter with the new rules and standards of the Customs Union.

Pros and cons of the CU to

Kazakhstan.

Despite all the difficulties of its inception period,

the Customs Union is a huge step towards optimizing the conditions for the

economic development of its member states. The total integration benefit from

the establishment of the Customs Union is estimated to reach about $400 billion

by 2015. The experts believe that the dissolution of customs barriers to mutual

trade between the three countries will ensure the growth of their mutual GDP by

15-20% by 2015 [19].

With the Customs Union in effect Kazakhstan raised

customs duties on imports of goods from other countries; however the VAT rate

remained unchanged (at 12% compared with 18% in Russia and Belarus). Being a

member of the Customs Union Kazakhstan will discover not only new possibilities

but new challenges as well. The higher import duties will lead to a slight

increase in domestic prices, and inflation

will rise by 0.5-0.7%. However, the rise in the inflation is expected to

level out if Kazakhstan reduces imports, replacing them with domestic products.

Despite the general perception of Customs Union as a

treaty to promote free trade it also has features to protect the internal

market from foreign influence. As we see on the graph 4 below the

decision-making process within the Union is highly-dependent on the position of

Russia, which enjoys the effective veto right within the union. Therefore the

possible worsening of the stance of Kazakhstan and Belarus towards promoting

free trade is now a function of Russia external affairs and political

decisions.

Figure 4. Decision making

process in the Commission of the Customs Union

Source: Holzacker

H. (2010) Presentation given on 25 January 2010 in Brussels ‘Custom Union: no

big inflation shock, but efforts needed to offset impact on non-resources

sectors’ An analysis by ATF Bank

Research. Available at official web-site of the Customs Union of Belarus,

Kazakhstan and Russia: http://tsouz.ru/news/Documents/Custom_Union

_Glaziev1.pdf (accessed

26 November 2010).

Today, the prospects of expanding the membership of CU

are already being discussed, as Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine all

announced their intention to join. Finally, the Presidents of the three Customs

Union countries adopted a decision to create a single economic space – a task

that is expected to take two years to complete. The intention to join the WTO

as a single regional grouping that was announced by Belarus, Kazakhstan and

Russia provoked wide international response. Eventually the three countries

settled on joining the WTO individually, but in a coordinated manner.

In conclusion we can say that there are some

widely-known benefits of the free trade:

·

First is the

efficiency of free trade. Trade potentially benefits a country through

expansion economy’s choices, thus, it is always possible to redistribute income

in such a way which would be beneficial for everyone.

·

Second is

economy of scale. Protected markets reduce competition and led too many domestic

firms to enter the protected industry. Because of the proliferation of firms in

narrow domestic markets, the scale of production of each firm becomes

inefficient.

·

Third is

providing entrepreneurs with new ways to export or compete with imports, thus,

free trade offer more opportunities for learning and innovation.

·

Fourth, the

strong mutually-beneficial trading relationships are a bail to have a war with

trade-partner.

·

Fifth is

a free trade agreement. It is economically efficient for a good to be produced

by the country which is the lowest cost producer, but this will not always take

place if a high cost producer has a free trade agreement while the low cost

producer faces a high tariff. Applying free trade to the high cost producer can

lead to trade diversion and a net economic loss.

As we see from upper mentioned

arguments global free trade is a net benefit to society. However, there are also some disadvantages that

could be avoided.

·

First

is a necessary protection of industries related to national defense. If

in those industries would dominate foreign competitors, then these industries

may find themselves in a difficult position in war situation.

·

Second

is infant industry argument. Protectionists believe that infant industries

must be protected in order to allow them to grow to a point where they can compete

in the global market.

·

Third is

a protection of the more developed countries from competition of cheaper

foreign labor. Since the foreign labor is much cheaper than domestic, domestic labor is

forced to gradually decrease their income in order to be competitive.

·

Fourth

are possible improvement countries terms of trade through optimal tariffs

and export taxes. However, this argument is not too important in practice.

Small countries cannot have much influence on their import or export prices, so

they cannot use tariffs or other policies to raise their terms of trade. On the

other hand, large countries can influence their terms of trade, but in imposing

tariffs they run the risk of disrupting trade agreements and provoking

retaliation.

·

Fifth are

domestic market failures. If some domestic market, such as labor market, fails

to function properly, deviating from free trade can sometimes help reduce the

consequences of this malfunctioning. The theory of the second best choice that

if one market fails to work properly it is no longer optimal for government to

abstain from intervention in other markets. A tariff may raise welfare if there

is a marginal social benefit to production of a good that I not captured by

producer surplus measures.

Even

though inadequacy of most of the arguments in favor of protectionism is proved

both in theory and in practice, some degree of protectionism is nevertheless the norm

throughout the world.

In case of Kazakhstan we see clear trend towards

developing free trade, both globally and regionally with WTO accession and CU

formation being the main current developments and milestones for shaping the

future state of being.

Being a member of the CU will provide Kazakhstan with

the following benefits…:

- help to optimize the conditions for the economic

development with CU member states;

- the promotion of mutual trade between the CU

countries will ensure the growth of their mutual GDP by 15-20% and secure the

integration benefit of $400bn by 2015.

… and additional challenges:

- increased import duties will drive domestic prices,

and inflation will rise by 0.5-0.7%.

- the tariff policy will now be highly dependent on

the external trade policy of Russia, which means lower flexibility for

Kazakhstan in adapting its economic policy to external shocks.

References:

1. Library of economics and

liberty (2008) Available at: http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/

bios/Ricardo.html (accessed 23 November 2010)

2. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy,

p. 213

3. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy,

p. 73

4. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy, p. 213

5. Cline cited in Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy,

p. 214, table 9-1

6. Steven, p 235-245

7. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy, p. 214

8. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy, p. 214

9. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International

economics: Theory and Policy, p. 215

10. Steven, p 235-245

11. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy, p. 243

12. Krugman P. and Obsfeld M., (2009), International economics: Theory and Policy, p. 243

13. Chipman (1965), p.477-519;

Shiozawa (2007), p. 141-187

14. Mankiw (2007), Shiozawa

(2009), p.19-37

15. Shiozawa (2007), p. 141-187

16. Vinokurov, Libman (2010), p.

141-150

17. Holzacker H. (2010) ‘Custom

Union: no big inflation shock, but efforts needed to offset impact on

non-resources sectors’ An analysis by ATF

Bank Research. Available at: www.atfbank.kz (accessed 26 November 2010)

18. Holzacker H. (2010)

Presentation given on 25 January 2010 in Brussels ‘Custom Union: no big inflation shock, but efforts needed to offset

impact on non-resources sectors’ an analysis by ATF Bank Research. Available

at official web-site of the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia: http://tsouz.ru/news/Documents/Custom_Union

_Glaziev1.pdf (accessed

26 November 2010).

19. Vinokurov E., Libman A. (2010)

‘The EDB System of indicators of Eurasian

Integration: General Findings’, Yearbook 2010, p.136-154